This section examines the evidence for human evolution — from foundational concepts like deep time, natural selection, and genetics to the fossil record documenting human origins through a continuous series of species stretching back seven million years. 30 articles covering 73 key specimens demonstrate that Homo sapiens arose through natural processes. Every claim is sourced to peer-reviewed research.

Foundations of evolution

- The earth is 4.5 billion years oldRadiometric dating, ice cores, tree rings, and varves independently converge on a 4.54-billion-year-old Earth — providing ample time for evolutionary processes.

- Evolution is both fact and theoryIn science, "theory" means a well-tested explanatory framework, not a guess. Evolution is both observed fact and predictive theory — like gravity, germ theory, and plate tectonics.

- Genetic change creates new functionsLactase persistence, nylon-eating bacteria, the E. coli long-term evolution experiment, gene duplication, and human chromosome 2 fusion all demonstrate that mutations create new functions.

- Natural selection builds complexityFrom the stepwise evolution of the eye to the bacterial flagellum's origin from the Type III secretion system, natural selection builds complexity incrementally through variation and differential reproduction.

- The origin of life is a chemical problemAbiogenesis is distinct from evolution. The Miller-Urey experiment, RNA world hypothesis, protocells, and hydrothermal vent chemistry reveal plausible pathways from simple molecules to living systems.

- Evolution is unguided but not randomMutation, natural selection, genetic drift, and gene flow produce adaptation without foresight. The illusion of design is explained by cumulative selection — and intelligent design fails as science.

Lines of evidence

- Human chromosome 2 is two fused ape chromosomesAll great apes have 48 chromosomes; humans have 46. Human chromosome 2 has telomeric repeats in its middle, a vestigial centromere, and banding patterns that match two chimpanzee chromosomes exactly.

- Humans carry broken vitamin C genesThe GULO pseudogene — broken by identical mutations in humans, chimps, gorillas, and orangutans — is a molecular fossil of shared ancestry. Guinea pigs lost the same gene independently, via a different mutation.

- Human embryos develop and lose tails, gill arches, and lanugoHuman embryos grow pharyngeal arches homologous to fish gills, a tail with vertebrae that is later resorbed, a coat of fine fur, and a yolkless yolk sac — recapitulating our evolutionary history.

- Humans share endogenous retroviruses with other primatesAbout 8% of the human genome is ancient viral DNA. Thousands of these retroviruses sit at identical chromosomal locations in humans and other primates — inherited from common ancestors.

- Human DNA is 98.7% identical to chimpanzee DNAThe 2005 chimpanzee genome project confirmed 98.7% identity in aligned sequences. The differences that exist — in FOXP2, HAR1, and gene regulation — illuminate what makes us human.

- The human body is full of evolutionary leftoversThe appendix, wisdom teeth, coccyx, goosebumps, palmaris longus, Darwin's tubercle, and the vestigial third eyelid are anatomical remnants of our mammalian and primate ancestry.

Earliest hominins (7–4.2 Ma)

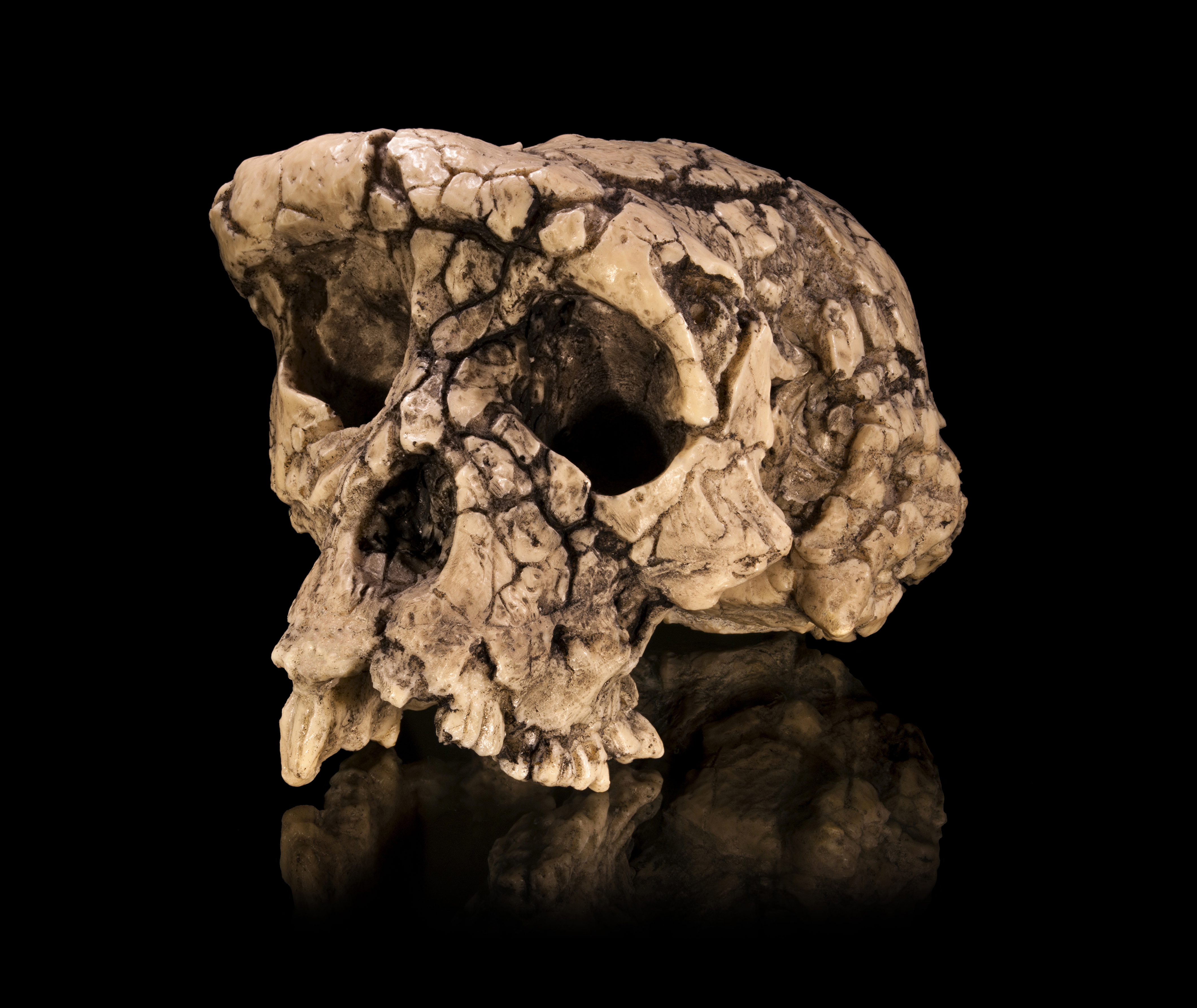

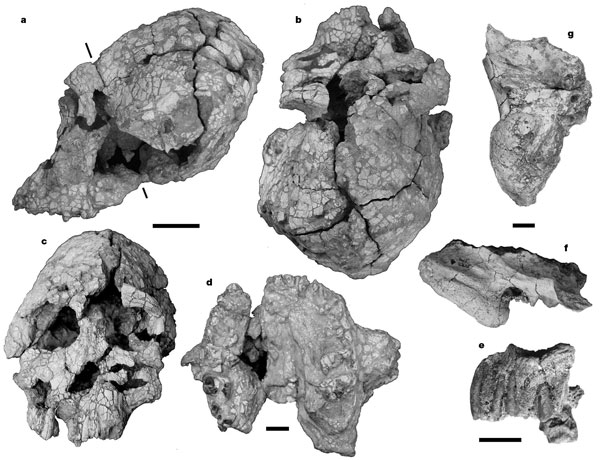

Sahelanthropus tchadensisThe oldest known potential hominin, discovered in Chad in 2001 and dated to ~7 million years ago. The Toumaï cranium's anteriorly positioned foramen magnum suggests upright posture.

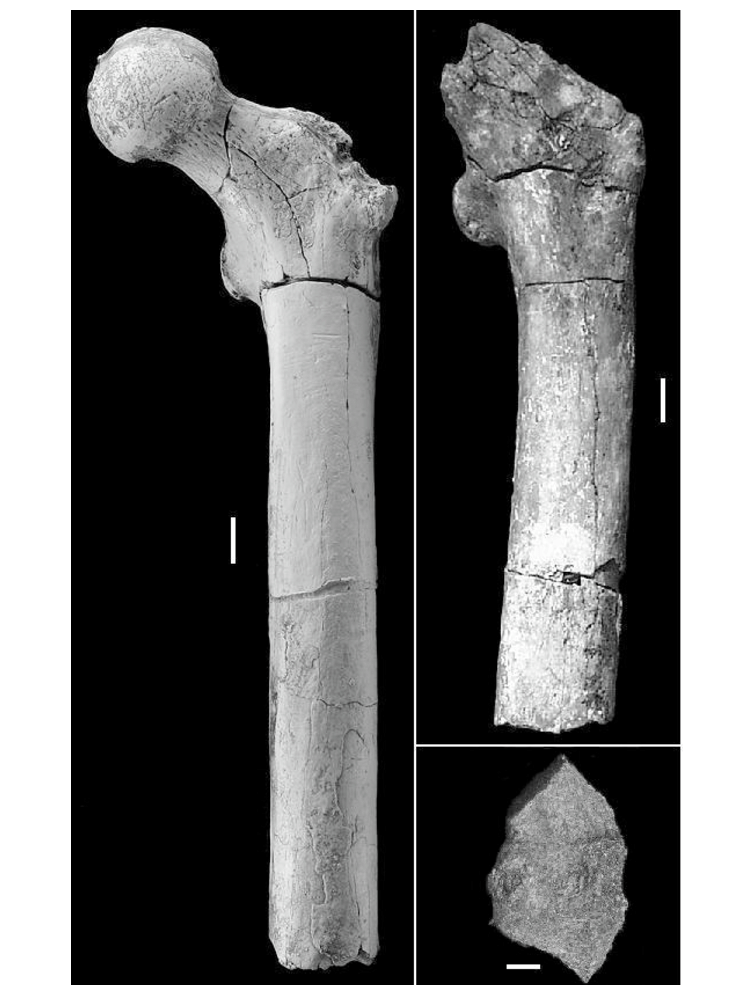

Sahelanthropus tchadensisThe oldest known potential hominin, discovered in Chad in 2001 and dated to ~7 million years ago. The Toumaï cranium's anteriorly positioned foramen magnum suggests upright posture. Orrorin tugenensisFemoral evidence from the Tugen Hills of Kenya provides the earliest postcranial evidence of bipedalism at ~6 million years ago.

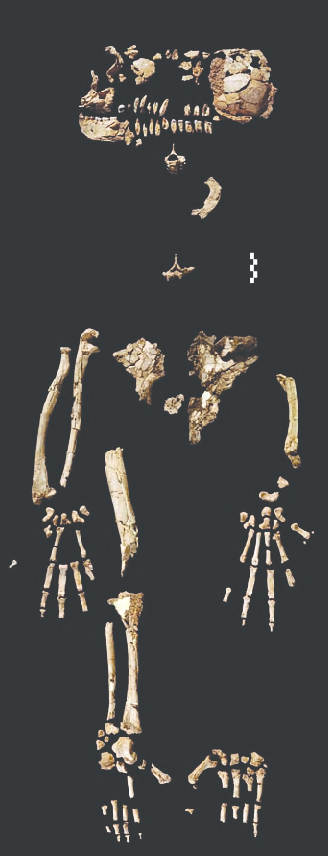

Orrorin tugenensisFemoral evidence from the Tugen Hills of Kenya provides the earliest postcranial evidence of bipedalism at ~6 million years ago. ArdipithecusAr. kadabba and Ar. ramidus, including the famous "Ardi" skeleton, reveal a mosaic of bipedal and arboreal features in a woodland habitat, overturning the savanna hypothesis.

ArdipithecusAr. kadabba and Ar. ramidus, including the famous "Ardi" skeleton, reveal a mosaic of bipedal and arboreal features in a woodland habitat, overturning the savanna hypothesis.

Australopithecus (4.2–2.0 Ma)

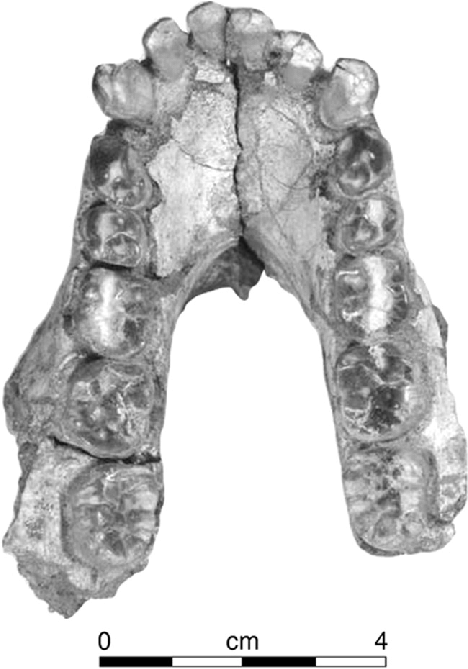

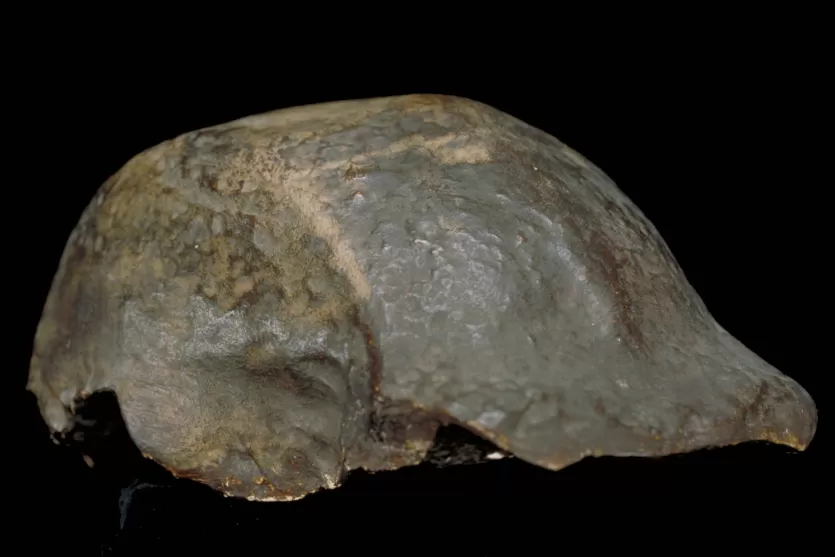

Australopithecus anamensisThe earliest unambiguous australopithecine. The 2019 MRD cranium gave this species a face for the first time and demonstrated temporal overlap with A. afarensis.

Australopithecus anamensisThe earliest unambiguous australopithecine. The 2019 MRD cranium gave this species a face for the first time and demonstrated temporal overlap with A. afarensis. Australopithecus afarensisThe species of Lucy, Selam, and the First Family. Valgus knee, Laetoli footprints, and pelvic anatomy prove bipedalism by 3.7 million years ago.

Australopithecus afarensisThe species of Lucy, Selam, and the First Family. Valgus knee, Laetoli footprints, and pelvic anatomy prove bipedalism by 3.7 million years ago. Australopithecus africanusThe Taung Child, Mrs. Ples, and Little Foot. Dart's 1924 discovery validated African human origins after decades of rejection by a Eurocentric establishment.

Australopithecus africanusThe Taung Child, Mrs. Ples, and Little Foot. Dart's 1924 discovery validated African human origins after decades of rejection by a Eurocentric establishment. Later Australopithecus speciesA. garhi, A. sediba, and A. deyiremeda reveal a diverse radiation of species at the australopith-to-Homo transition, challenging linear models of evolution.

Later Australopithecus speciesA. garhi, A. sediba, and A. deyiremeda reveal a diverse radiation of species at the australopith-to-Homo transition, challenging linear models of evolution.

Paranthropus and Kenyanthropus (3.5–1.0 Ma)

Kenyanthropus platyopsA 3.5-million-year-old flat-faced hominin from Kenya that challenges A. afarensis as the sole ancestor of later hominins and may be linked to the earliest stone tools.

Kenyanthropus platyopsA 3.5-million-year-old flat-faced hominin from Kenya that challenges A. afarensis as the sole ancestor of later hominins and may be linked to the earliest stone tools.ParanthropusThree species of "robust" australopithecines with massive jaws and megadont molars — an evolutionary experiment in powerful chewing that persisted alongside early Homo for over a million years.

Early Homo (2.5–0.1 Ma)

Homo habilis and Homo rudolfensisThe earliest members of genus Homo, with expanded brains and the first stone tools. The "handy man" marks the transition from Australopithecus.

Homo habilis and Homo rudolfensisThe earliest members of genus Homo, with expanded brains and the first stone tools. The "handy man" marks the transition from Australopithecus. Homo erectusThe longest-surviving human species (~2 million years). From Dubois's "missing link" to the Dmanisi revolution, Turkana Boy's modern proportions, and Peking Man's lost fossils.

Homo erectusThe longest-surviving human species (~2 million years). From Dubois's "missing link" to the Dmanisi revolution, Turkana Boy's modern proportions, and Peking Man's lost fossils.

Middle Pleistocene (800–200 ka)

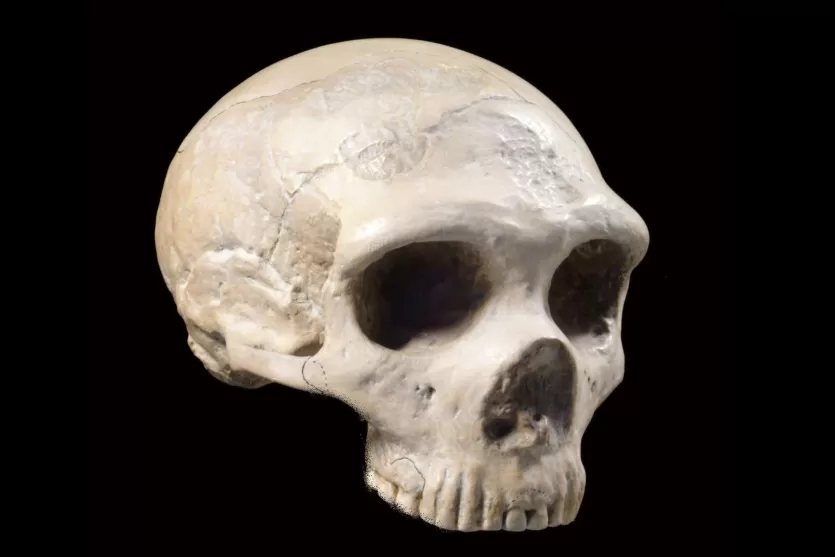

Homo heidelbergensisThe last common ancestor of Neanderthals, Denisovans, and modern humans. The Sima de los Huesos "pit of bones" yielded 28+ individuals with proto-Neanderthal DNA.

Homo heidelbergensisThe last common ancestor of Neanderthals, Denisovans, and modern humans. The Sima de los Huesos "pit of bones" yielded 28+ individuals with proto-Neanderthal DNA. Homo nalediA small-brained hominin from Rising Star Cave, contemporaneous with early H. sapiens. 1,550+ specimens suggest deliberate body disposal — with a brain one-third the size of ours.

Homo nalediA small-brained hominin from Rising Star Cave, contemporaneous with early H. sapiens. 1,550+ specimens suggest deliberate body disposal — with a brain one-third the size of ours.

Island species

Late Pleistocene diversity (300–30 ka)

NeanderthalsSophisticated humans who buried their dead, cared for the injured, created art, and interbred with Homo sapiens. Their DNA lives on in 1–4% of non-African genomes today.

NeanderthalsSophisticated humans who buried their dead, cared for the injured, created art, and interbred with Homo sapiens. Their DNA lives on in 1–4% of non-African genomes today. DenisovansAn archaic human population identified from a single finger bone's DNA. The 2025 Harbin cranium confirmation gave Denisovans a face — and their genes gave Tibetans the ability to breathe at altitude.

DenisovansAn archaic human population identified from a single finger bone's DNA. The 2025 Harbin cranium confirmation gave Denisovans a face — and their genes gave Tibetans the ability to breathe at altitude.

Homo sapiens (315 ka–present)

Early Homo sapiens in AfricaJebel Irhoud, Omo Kibish, Herto, and Florisbad reveal that our species originated across Africa more than 300,000 years ago — with a modern face evolving before a modern braincase.

Early Homo sapiens in AfricaJebel Irhoud, Omo Kibish, Herto, and Florisbad reveal that our species originated across Africa more than 300,000 years ago — with a modern face evolving before a modern braincase. Homo sapiens: out of AfricaThe global dispersal from Africa through the Levantine corridor to every continent, interbreeding with Neanderthals and Denisovans along the way. The grand finale of the fossil record.

Homo sapiens: out of AfricaThe global dispersal from Africa through the Levantine corridor to every continent, interbreeding with Neanderthals and Denisovans along the way. The grand finale of the fossil record.