An example of ripples found in the Hakatai Shale, indicating a shallow marine environment during deposition.

The Grand Canyon's features provide compelling evidence for an Earth that is far older than a few thousand years. Below are some lines of evidence that support an old earth and the problems that arrive from a Young Earth assumption.

The Bible suggests that the entire earth (and thus the Grand Canyon) are only a few thousand years old. Scientific data suggests that the Grand Canyon is billions of years old.

The Grand Canyon's rock layers demonstrate the principle of superposition, which states that in undisturbed rock sequences, the oldest layers are at the bottom and the youngest at the top. The canyon exposes nearly 40 major sedimentary rock layers, with a total thickness of about 4,000 to 5,000 feet (1,200 to 1,500 meters).

Data: The Tapeats Sandstone, one of the lowest layers, is about 100 feet (30 meters) thick and contains billions of sand grains. If we assume a generous deposition rate of 1 foot per day (which is much faster than observed rates), it would still take over 3 months just to form this single layer. Given that there are dozens of layers, many much thicker than the Tapeats, the total time required for deposition alone would far exceed the timeframe proposed by young Earth models.

Problem: To fit these layers into a young Earth timeframe would require catastrophic deposition rates that are not observed in nature and would destroy the fine layering and preserved features (like mudcracks and ripple marks) seen in many of the canyon's rocks.

An example of ripples found in the Hakatai Shale, indicating a shallow marine environment during deposition.

Many of the Grand Canyon's layers consist of sedimentary rocks, which form through the slow accumulation and compression of sediments. These layers also contain fossils that show a progression of life forms over time.

Data: The Redwall Limestone layer is up to 800 feet (240 meters) thick and is composed primarily of the remains of marine organisms. Modern coral reef growth rates are typically 0.3 to 2 centimeters per year. Even at the fastest rate, it would take over 12,000 years to form just this single layer.

Problem: A young Earth model would require explaining how diverse marine ecosystems could evolve, thrive, die, be buried, and lithify into solid rock multiple times within a few thousand years. This contradicts observed biological and geological processes.

An example of animal tracks found in the Coconino Sandstone, the third highest layer of sediment at the Grand Canyon.

The Grand Canyon itself is a product of erosion by the Colorado River. The rate of erosion can be observed and measured today, allowing geologists to estimate how long it would take to carve out the entire canyon.

Data: The average erosion rate of the Colorado River is estimated at about 0.1 to 0.5 millimeters per year. The canyon is about 1 mile (1.6 km) deep at its deepest point. At the fastest observed erosion rate, it would take at least 3.2 million years to erode to its current depth.

Problem: To erode the canyon in a few thousand years would require erosion rates hundreds of times faster than what we observe today. Such rates would cause catastrophic destruction not seen in the carefully preserved rock layers and delicate formations within the canyon.

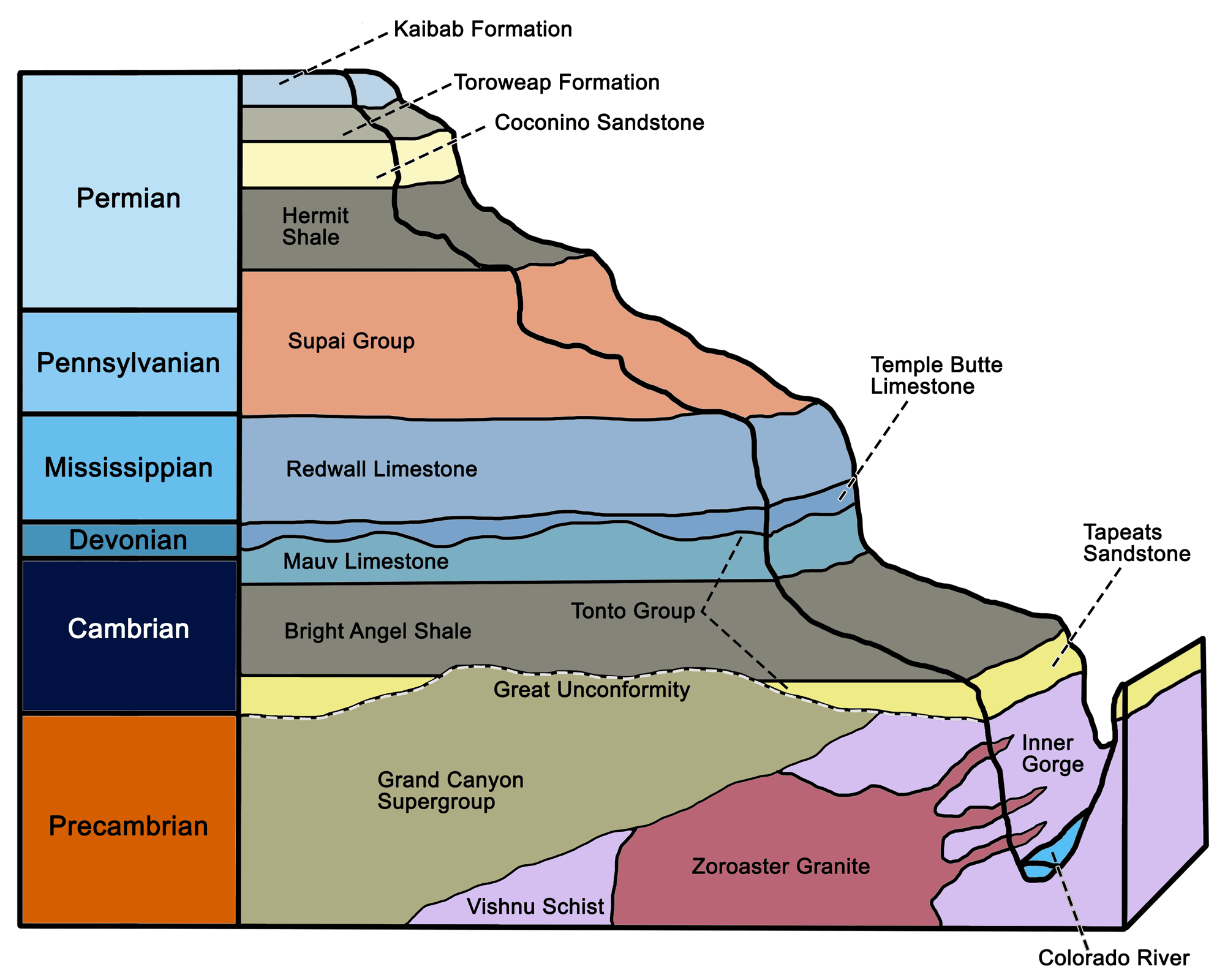

A diagram showing the different sedimentary layers in the Grand Canyon and the time periods to which they belong.

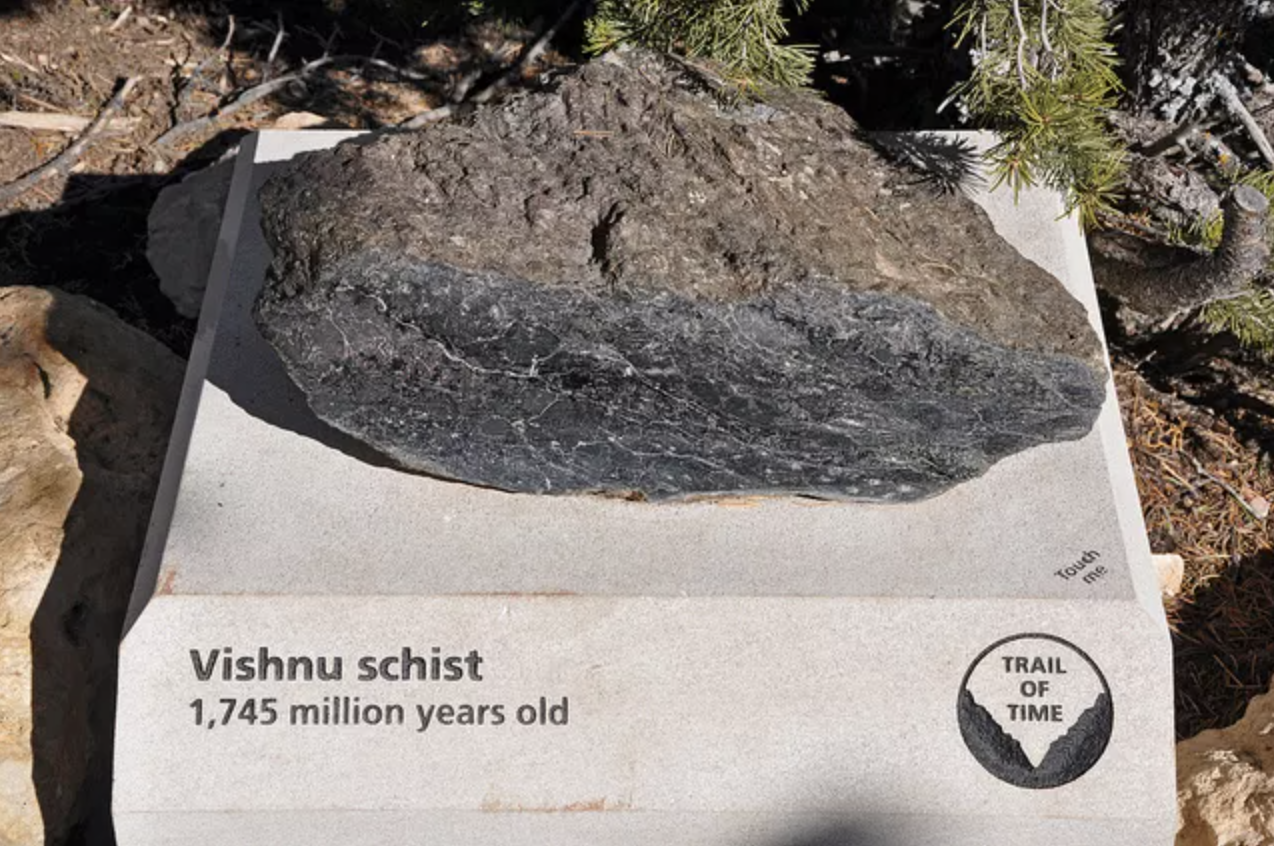

The presence of metamorphic rocks like the Vishnu Schist and igneous intrusions in the canyon indicates cycles of burial, heating, and mountain-building followed by erosion.

Evidence: The Vishnu Schist, found at the bottom of the canyon, shows evidence of being buried up to 25 kilometers deep before being uplifted and exposed. The rate of tectonic uplift typically ranges from 0.1 to 10 millimeters per year. Even at the fastest rate, it would take 2.5 million years to uplift this rock from its deepest burial.

Young Earth Problem: A young Earth model would need to explain how rocks could be buried deep enough to metamorphose, then be uplifted and exposed, all within a few thousand years. This would require rates of geological processes far beyond anything observed or physically plausible.

A slab of Vishnu schist rock, a type of igneous rock found at the bottom of the Grand Canyon.

The geological evidence presented by the Grand Canyon strongly supports the conclusion of an old Earth. Each aspect of the canyon's geology points to processes that require vast amounts of time, far exceeding a few thousand years.

Additional Problems: