Australopithecus anamensis occupies a pivotal position in the human fossil record as the earliest species that can be confidently assigned to the genus Australopithecus. Known from fossils spanning approximately 4.2 to 3.8 million years ago, it bridges the gap between the more primitive Ardipithecus and the better-known Australopithecus afarensis, the species represented by the famous "Lucy" skeleton.1, 2 For decades, A. anamensis was known primarily from jaws, teeth, and limb bones, leaving its facial appearance a mystery. That changed dramatically in 2019, when a near-complete cranium from Ethiopia gave this species a face for the first time and upended prevailing assumptions about how one australopithecine species gave rise to another.3, 4

Discovery and naming

The first fossil now attributed to A. anamensis was discovered before the species had a name. In 1965, Bryan Patterson of Harvard University recovered a distal humerus fragment, catalogued as KNM-KP 271, from Pliocene sediments at Kanapoi in the west Turkana region of Kenya.5, 6 At the time, the fragment could not be confidently assigned to any known species, and it languished in relative obscurity for nearly three decades. Early potassium-argon dating placed the Kanapoi sediments at approximately 4 million years old, making the humerus one of the oldest hominin postcranial fossils then known, but its taxonomic significance was not fully appreciated until the 1990s.5

The breakthrough came in 1994 when Meave Leakey and her team returned to Kanapoi and to the nearby site of Allia Bay on the eastern shore of Lake Turkana. Over two field seasons, they recovered a substantial collection of hominin fossils including mandibles, isolated teeth, a tibia, and additional postcranial fragments.1 In 1995, Leakey, Craig Feibel, Ian McDougall, and Alan Walker formally described these specimens as a new species, Australopithecus anamensis, selecting as the type specimen a partial mandible with dentition from Kanapoi designated KNM-KP 29281.1 The species name derives from "anam," the word for "lake" in the Turkana language, reflecting the proximity of the fossil sites to Lake Turkana.1

Subsequent fieldwork greatly expanded the A. anamensis hypodigm. Renewed excavations at Kanapoi between 2003 and 2008 yielded nine additional fossils, and further campaigns from 2012 to 2015 produced yet more specimens, bringing the total Kanapoi collection to approximately 69 catalogued hominin fossils.7, 8 Beyond Kanapoi and Allia Bay, fossils attributed to A. anamensis have been recovered from Asa Issie in the Middle Awash region of Ethiopia, dated to approximately 4.1–4.2 million years ago, and from the Woranso-Mille study area in the central Afar region of Ethiopia.9, 10 The geographic range of the species thus extends across a substantial portion of the East African Rift System.

Geological context and dating

The Kanapoi Formation, first described by Patterson in 1966, preserves a sequence of Pliocene sediments deposited in a variety of fluvial and lacustrine environments along the southwestern margin of Lake Turkana.5, 11 The hominin-bearing deposits are bracketed by volcanic tuffs that have been dated using the 40Ar/39Ar method. The lower tuff yields an age of approximately 4.195 million years, while the upper tuff dates to approximately 4.108 million years, constraining the age of the Kanapoi hominin fossils to a narrow interval of roughly 90,000 years centered around 4.1–4.2 million years ago.7, 12

Fossils from Allia Bay are somewhat younger, dated to approximately 3.9 million years ago based on their stratigraphic position relative to dated tephra layers in the Koobi Fora Formation.1, 12 The Asa Issie specimens from Ethiopia fall within the same temporal range as the Kanapoi material, at approximately 4.1–4.2 million years ago.9 Geological, sedimentological, isotopic, and faunal data from Kanapoi indicate that the paleoenvironments were highly heterogeneous, with significant topographic relief, marked seasonality, abundant freshwater resources, and a rich assemblage of aquatic and terrestrial vertebrates including fish, crocodiles, hippopotami, bovids, and suids.11

Anatomy and morphology

The comprehensive monograph by Carol Ward, Meave Leakey, and Alan Walker, published in 2001, remains the definitive morphological description of A. anamensis. Their analysis of specimens from both Kanapoi and Allia Bay revealed a species that was in many respects intermediate between earlier hominins such as Ardipithecus and the later A. afarensis, though it possessed its own distinctive combination of features.2

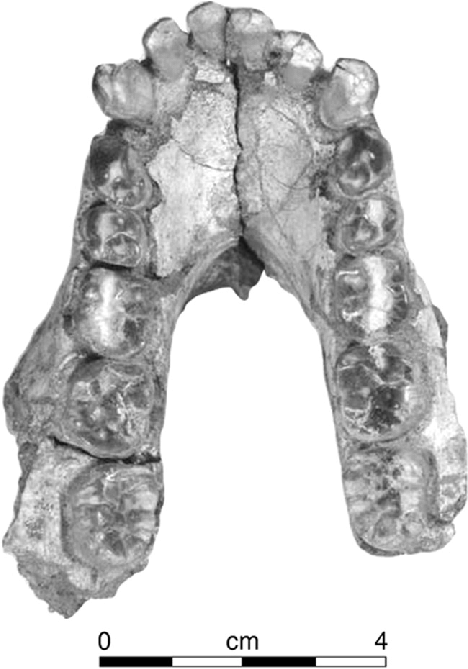

The mandible is one of the best-represented elements of the skeleton. The holotype, KNM-KP 29281, preserves a partial mandible with a U-shaped dental arcade, in contrast to the more rectangular shape seen in great apes.1, 2 The mandibular corpus is deep and robust, with a long and narrow symphyseal region (the midline where the two halves of the jaw meet), features that distinguish it from both Ardipithecus and living apes.2 The mandibular ramus is broad and tall, suggesting powerful masticatory musculature.2

The dentition provides important evidence about both diet and evolutionary relationships. The canine teeth are large relative to later Australopithecus species but reduced compared to those of apes, a pattern consistent with the broader trend of canine reduction across hominin evolution.1, 2 The postcanine teeth, the premolars and molars, are enlarged with low crowns and notably thick enamel, features that indicate adaptation to hard, brittle foods and represent a clear departure from the thin-enameled condition seen in Ardipithecus and living great apes.2, 13 Studies of dental microwear and enamel microstructure suggest that A. anamensis consumed a diet that included hard, brittle items such as seeds and nuts, supplemented by softer foods including fruits, with a masticatory repertoire more similar to that of gorillas than to chimpanzees in the range of loading directions employed during chewing.13, 14

The postcranial skeleton, though fragmentarily preserved, provides the strongest evidence that A. anamensis was a habitual biped. The tibia from Kanapoi (KNM-KP 29285) is particularly informative. Both the proximal (knee-end) and distal (ankle-end) surfaces are expanded relative to the shaft, indicating that substantial body weight was being transmitted through this bone during locomotion, a hallmark of bipedality.2, 15 The tibial plateau, where the tibia articulates with the femur at the knee, is oriented perpendicular to the long axis of the shaft, as in all later hominins, indicating that the knee was positioned directly over the ankle during the single-limb support phase of walking.2, 15 The distal humerus fragment originally recovered by Patterson in 1965 also shows features consistent with bipedal locomotion: the carrying angle and overall morphology of the elbow joint are more human-like than ape-like, suggesting that the arms were no longer primarily weight-bearing during locomotion.5, 2

The MRD cranium

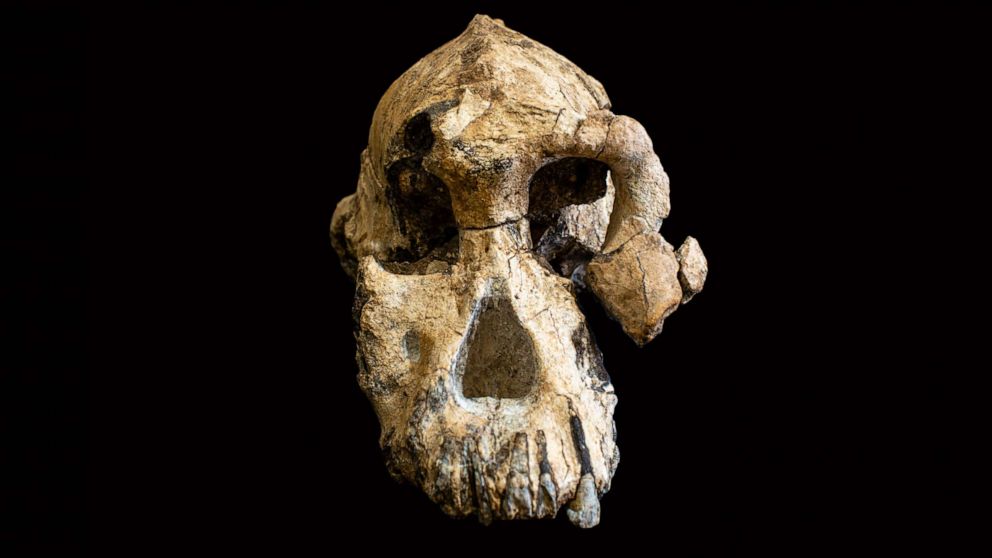

For more than two decades after the species was named, no cranium of A. anamensis was known. This gap meant that fundamental questions about the species' brain size, facial architecture, and overall cranial morphology remained unanswered. That changed on February 10, 2016, when Ali Bereino, a local Afar worker on Yohannes Haile-Selassie's field team, spotted the upper jaw of a hominin eroding from sediments at Miro Dora in the Woranso-Mille study area of the Afar Region, Ethiopia.3

The specimen, designated MRD-VP-1/1 (commonly referred to as "MRD"), proved to be a near-complete cranium, the first ever recovered for A. anamensis. Haile-Selassie and colleagues published their description of MRD in two companion papers in Nature in August 2019, one describing the cranium's morphology and taxonomy, the other establishing its age and evolutionary implications.3, 4 The cranium was dated to approximately 3.8 million years ago based on the stratigraphic position of the fossil relative to dated volcanic layers, making it the youngest known specimen of A. anamensis.4

The MRD cranium revealed an unexpectedly primitive face. The braincase is small, with a preliminary endocranial volume estimate of approximately 365–370 cubic centimeters, placing it at the lower end of the range for Australopithecus and comparable to a modern chimpanzee.3, 16 The face is long, markedly prognathic (projecting forward), and laterally broad, with large, anteriorly placed zygomatic bones (cheekbones).3 A well-developed sagittal crest runs along the midline of the braincase, indicating the attachment of powerful temporalis muscles used in chewing, a feature more commonly associated with the robust australopithecines (Paranthropus) and male gorillas.3 The preserved right canine is among the largest known for any early hominin, particularly in its mesiodistal (front-to-back) dimension.3

Haile-Selassie and colleagues identified MRD as A. anamensis rather than A. afarensis based on a suite of primitive features including the morphology of the canine, the shape of the temporal bone, and the configuration of the cranial base.3 The MRD cranium shares more features with the known mandibular and dental specimens of A. anamensis from Kanapoi and Allia Bay than with the cranial material of A. afarensis from Hadar and Laetoli.3 At the same time, the cranium displays a mosaic of features: some aspects of the facial skeleton are more derived (closer to the A. afarensis condition) than the mandibular specimens from Kanapoi, suggesting considerable morphological variability within the species.3

Key specimens

Major Australopithecus anamensis specimens1, 2, 3, 7

| Specimen | Element | Age (Ma) | Site | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KNM-KP 271 | Distal humerus | ~4.1 | Kanapoi, Kenya | First fossil discovered (1965); human-like elbow morphology |

| KNM-KP 29281 | Partial mandible | 4.05 ± 0.15 | Kanapoi, Kenya | Holotype; U-shaped arcade; thick molar enamel |

| KNM-KP 29285 | Tibia (proximal + distal) | ~4.1 | Kanapoi, Kenya | Key evidence for bipedalism; human-like knee and ankle orientation |

| KNM-ER 20422 | Temporal fragment | ~3.9 | Allia Bay, Kenya | Earliest specimen from Allia Bay |

| ARA-VP-14/1 | Partial maxilla | ~4.1–4.2 | Asa Issie, Ethiopia | Extended geographic range to the Middle Awash |

| MRD-VP-1/1 | Near-complete cranium | 3.8 | Woranso-Mille, Ethiopia | First A. anamensis face; ~370 cc; demonstrates temporal overlap with A. afarensis |

The Kanapoi collection is by far the richest single assemblage, comprising mandibles, a partial temporal bone, a maxilla, at least eight associated partial dentitions from both juvenile and adult individuals, more than 20 isolated teeth, and postcranial fragments including a humerus, manual phalanx, capitate, and the diagnostic tibia.2, 7 The Allia Bay sample adds a nearly complete radius and several maxillary fragments and isolated teeth.1, 2 Collectively, these specimens document a species with a body size estimated at roughly 45–55 kilograms and modest sexual dimorphism, broadly comparable to the later A. afarensis.2, 16

Evidence for bipedalism

The postcranial evidence from A. anamensis provides some of the oldest unambiguous anatomical markers of habitual bipedal locomotion in the hominin fossil record. While earlier species such as Ardipithecus ramidus show some features consistent with upright walking, the evidence is debated and the locomotor repertoire of Ardipithecus appears to have included substantial arboreal climbing.17 In A. anamensis, the postcranial adaptations to bipedality are clearer and more numerous.2

The tibia KNM-KP 29285 is the single most important postcranial specimen. Ward and colleagues documented several features that are functionally linked to bipedal weight-bearing.2 The tibial plateau is substantially larger than in living great apes of comparable body size, reflecting the greater loads transmitted through the knee during bipedal stance.2, 15 The orientation of the proximal articular surface is perpendicular to the long axis of the shaft, identical to the condition in modern humans and all later hominins, and distinct from the angled orientation seen in quadrupedal apes.2 At the ankle end, the talocrural joint surface is oriented to accommodate the direct transmission of body weight from a vertically positioned leg, again matching the human pattern.2, 15

The distal humerus KNM-KP 271 adds complementary evidence. Its morphology suggests that the upper limb was not being used for habitual weight-bearing during locomotion, as it would be in a knuckle-walking ape.5, 2 Together, the lower limb evidence for bipedal weight-transfer and the upper limb evidence for release from locomotor function paint a consistent picture of a species that had committed to terrestrial bipedality as its primary mode of locomotion by at least 4.2 million years ago, even while retaining some primitive features that may reflect residual climbing ability.2

Cranial capacity comparison across early hominins3, 16, 17

Temporal overlap and the anagenesis debate

Prior to 2019, the prevailing view of the relationship between A. anamensis and A. afarensis was one of simple anagenesis: the older species gradually transformed into the younger one through incremental morphological change, with no period of coexistence.18 This model was attractive because the known temporal ranges of the two species appeared to be sequential. A. anamensis was documented from approximately 4.2 to 3.9 million years ago, while A. afarensis was known from approximately 3.7 to 3.0 million years ago, leaving a plausible transition interval but no overlap.18, 10 A 2006 study by Kimbel and colleagues formally tested the anagenesis hypothesis using dental and mandibular metrics and concluded that the two species could reasonably be interpreted as segments of a single evolving lineage.18

The MRD cranium disrupted this tidy picture. Dated to 3.8 million years ago, it pushed the last appearance of A. anamensis forward in time.4 Simultaneously, Haile-Selassie and colleagues reanalyzed a frontal bone fragment from the Woranso-Mille area, previously described by the same team in 2015, and identified it as belonging to A. afarensis rather than A. anamensis. This specimen, BRT-VP-3/1, is dated to approximately 3.9 million years ago, pushing the first appearance of A. afarensis back in time.4, 10 The combined effect was to establish a temporal overlap of at least 100,000 years during which both species coexisted in the Afar region of Ethiopia.4

This overlap has significant implications for understanding the mode of speciation. If A. anamensis and A. afarensis coexisted, then one could not have simply transformed into the other through gradual, population-wide change. Instead, the pattern is more consistent with cladogenesis: A. afarensis budded off from a subpopulation of A. anamensis, while the parent species persisted for a time alongside its descendant.3, 4 This would represent an example of a speciation event that can be directly observed in the hominin fossil record, a rare and valuable finding.4

Not all researchers have accepted this interpretation without reservation. Some have cautioned that the reassignment of the BRT-VP-3/1 frontal to A. afarensis rests on limited anatomical evidence, and that a single cranium should not overturn a model supported by decades of dental and mandibular comparison.19 Others have noted that the morphological boundary between A. anamensis and A. afarensis has always been somewhat fuzzy, with intermediate specimens making it difficult to draw a clean line between the two species, precisely the condition expected under anagenesis.18, 19 The debate remains active, but the MRD cranium has at minimum demonstrated that the evolutionary transition from A. anamensis to A. afarensis was more complex than a simple linear replacement.3, 4

Evolutionary significance

Australopithecus anamensis is significant for several reasons beyond its role in the A. afarensis transition. As the earliest unambiguous australopithecine, it documents the point at which the hominin lineage had clearly committed to bipedal locomotion while retaining a small, ape-sized brain.2, 3 This dissociation between locomotor and neurological evolution, with bipedality preceding significant brain expansion by at least two million years, is one of the most important patterns in the human fossil record. It demonstrates that upright walking, not intelligence, was the initial defining adaptation of the hominin lineage.20

The thick enamel and robust mandibular morphology of A. anamensis represent a significant dietary shift relative to earlier hominins. While Ardipithecus possessed thin-enameled teeth adapted to softer foods, A. anamensis shows clear adaptations for processing harder, more mechanically challenging items.2, 13 This shift likely reflects a transition to more open, seasonally variable environments in which reliance on fallback foods such as hard seeds and nuts became increasingly important, a dietary adaptation that would characterize the genus Australopithecus throughout its subsequent evolutionary history.11, 13

The geographic distribution of A. anamensis across multiple sites in Kenya and Ethiopia demonstrates that early australopithecines occupied a broad range of habitats within the East African Rift System.7, 9 Paleoenvironmental reconstructions from Kanapoi indicate a mosaic landscape including riverine forests, bushland, and more open grassland, suggesting that A. anamensis was an ecological generalist capable of exploiting diverse habitats.11 This ecological flexibility may have been a key factor in the success of the genus Australopithecus and, ultimately, in setting the stage for the emergence of the genus Homo.20

The MRD cranium's mosaic of primitive and derived features also bears on broader questions about hominin phylogeny. Its combination of a primitive cranial base and canine morphology with a more derived facial skeleton suggests that different regions of the skull evolved at different rates, a pattern known as mosaic evolution.3 This finding complicates attempts to reconstruct hominin evolutionary relationships based on a small number of anatomical features, and it underscores the importance of complete or near-complete specimens for understanding the full morphological range of extinct species.3, 4