Australopithecus africanus (meaning "southern ape of Africa") is a species of early hominin that lived in southern Africa between approximately 3.7 and 2.1 million years ago.1 It was the first australopithecine ever discovered, identified by the anatomist Raymond Dart in 1924 from a juvenile skull found at a limestone quarry near Taung, South Africa.2 The species occupies a pivotal place in the history of paleoanthropology: its discovery provided the earliest fossil evidence supporting Charles Darwin's 1871 prediction that the human lineage originated in Africa, and its eventual acceptance overturned decades of Eurocentric assumptions about human origins.3, 4

The Taung Child

In late 1924, workers at the Buxton Limeworks quarry near the village of Taung in what is now South Africa's North West Province blasted loose a block of limestone breccia containing a small fossilized skull.2 The quarry manager, A. E. de Bruyn, recognized the fossil's potential significance and forwarded it to Raymond Dart, a young Australian-born professor of anatomy at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg.5 Dart received the specimen on 28 November 1924 and immediately recognized features that distinguished it from any known ape: the foramen magnum, the opening through which the spinal cord exits the skull, was positioned forward beneath the cranium rather than toward the back, suggesting that the creature had walked upright.2, 6

Dart spent just over five weeks preparing and studying the specimen before publishing his analysis in the 7 February 1925 issue of Nature.2 He named the new genus and species Australopithecus africanus and argued that it represented an intermediate form between apes and humans. The skull belonged to a child approximately three to four years old at death, as indicated by its deciduous teeth and the first permanent molars just beginning to erupt.2, 7 The cranial capacity of the juvenile specimen was approximately 405 cc, with an estimated adult size of about 440 cc, larger than a chimpanzee of comparable age but far smaller than a modern human.8 Crucially, the specimen preserved a natural endocast, a limestone cast of the interior of the braincase, which Dart interpreted as showing an expanded occipital association cortex, a region involved in higher visual processing in humans.2, 9

Decades of rejection

The scientific establishment's response to Dart's claim was swift and largely negative. In the very next issue of Nature, four leading British anatomists published critical responses. Three of the four, Sir Arthur Keith, Grafton Elliot Smith, and Sir Arthur Smith Woodward, were members of the committee that had authenticated the Piltdown Man, a supposed fossil hominin "discovered" in England in 1912 that would not be exposed as a deliberate forgery until 1953.10, 11 Keith dismissed the Taung specimen as nothing more than a young ape, while Woodward insisted it could not be placed on the human family tree.5, 12

Several factors conspired against Dart. The Piltdown fraud had created the expectation that human ancestors should have large brains and ape-like jaws, the precise opposite of what A. africanus displayed: a small brain with human-like teeth.10, 13 There was also a deep-seated assumption that Asia or Europe, not Africa, was the cradle of humanity. Prominent researchers like Henry Fairfield Osborn favored Central Asian origins, and the idea of an African genesis struck many as implausible or even offensive to prevailing racial prejudices of the era.3, 14 Additionally, the fact that the Taung specimen was a juvenile made it easy for skeptics to argue that its seemingly human traits were merely those of an immature ape that would have developed more ape-like features as it matured.5

Dart was deeply affected by the rejection and largely withdrew from paleoanthropology for much of the next two decades, leaving the defense of Australopithecus to a crucial ally: the Scottish-born South African paleontologist Robert Broom.15

Broom's vindication and Sterkfontein

Robert Broom, already sixty-nine years old and an established authority on mammal-like reptiles, took up the search for adult australopithecines with extraordinary energy. In August 1936, the quarry manager at Sterkfontein, G. W. Barlow, handed Broom a natural endocast of an adult hominin from the cave's dolomitic breccia. Within days, Broom recovered much of the associated cranium, establishing the first adult specimen of a South African australopithecine.15, 16 Over the following years, Broom recovered additional specimens from Sterkfontein and from a second cave site at Kromdraai, where he identified the robust australopithecine Paranthropus robustus in 1938.17

The Sterkfontein caves, located about 40 kilometers northwest of Johannesburg in what is now the Cradle of Humankind UNESCO World Heritage Site (inscribed in 1999), have proven to be one of the richest sources of australopithecine fossils in the world, yielding more than 500 hominin specimens to date.18, 19 The site's dolomitic limestone created natural traps: animals and hominins fell through openings in the surface, and their bones became cemented in calcium carbonate breccia over millions of years. The caves contain multiple stratigraphic members, with Member 4, dated to roughly 2.6 to 2.0 million years ago, producing the bulk of the A. africanus material, and the deeper Member 2 preserving the older StW 573 skeleton.1, 20

Broom's most celebrated find at Sterkfontein came on 18 April 1947, when he and his assistant John Robinson recovered a remarkably complete adult cranium from Member 4. Broom initially assigned it to a new genus and species, Plesianthropus transvaalensis, and it became popularly known as "Mrs. Ples," though subsequent analysis has shown the specimen may actually be male.21, 22 The discovery of this near-complete adult skull, with its small canines, rounded cranium, and forward-positioned foramen magnum, made it far more difficult for skeptics to dismiss the australopithecines as mere apes.15

The turning point in public and scientific opinion came in 1947, the same year "Mrs. Ples" was found. Sir Arthur Keith, perhaps the most prominent of Dart's original critics, published a remarkable recantation: "Professor Dart was right and I was wrong."12, 15 The final blow to the opposition came in 1953, when Kenneth Oakley, Joseph Weiner, and Wilfrid Le Gros Clark exposed Piltdown Man as a deliberate forgery, a modern human cranium paired with an orangutan jaw that had been chemically treated to appear ancient.10 With Piltdown discredited, the small-brained, bipedal pattern exemplified by A. africanus was recognized as the true sequence of human evolution: upright walking preceded brain enlargement.13

Anatomy and morphology

Australopithecus africanus was a small-bodied hominin, standing approximately 1.1 to 1.4 meters tall, with an estimated body mass of 30 to 40 kilograms for females and up to about 41 kilograms for males, indicating moderate sexual dimorphism.1, 23 The cranium was rounded and relatively gracile compared to later robust australopithecines, lacking the pronounced sagittal crests and flared zygomatic arches seen in Paranthropus. Cranial capacities ranged from approximately 400 to 560 cc across known specimens, with a mean of about 460 cc, roughly a third the size of a modern human brain but larger than that of a chimpanzee of similar body mass.8, 24

Cranial capacity of key A. africanus specimens (cc)8, 24, 25

The dental morphology of A. africanus reflects a dietary shift compared to earlier hominins and modern apes. The canine teeth are reduced in size relative to great apes, lacking the large, projecting, interlocking canines characteristic of chimpanzees and gorillas. The premolars and molars are enlarged, with thick enamel, suggesting a diet that included hard or tough foods such as seeds, nuts, and tubers.1, 26 Microwear and stable isotope studies have revealed that A. africanus consumed a broader range of foods than A. afarensis, including significant quantities of C4 resources (grasses or sedges, or animals that consumed them), indicating adaptation to more open environments alongside woodland habitats.27

Evidence for bipedal locomotion in A. africanus comes from multiple anatomical features. The forward position of the foramen magnum, which Dart first recognized in the Taung Child, indicates that the head was balanced atop the spine as in modern humans rather than projecting forward as in quadrupedal apes.2, 6 The pelvis, best known from specimens like Sts 14, is broad and short in the manner of a biped, with a well-developed anterior inferior iliac spine for attachment of the rectus femoris muscle used in upright walking.23 The femur exhibits a valgus angle (angled inward from hip to knee), ensuring that the knee is positioned under the body's center of gravity during walking, a hallmark of habitual bipeds.1 At the same time, features of the hand and shoulder, including curved finger bones and a cranially oriented glenoid fossa, indicate that A. africanus retained significant arboreal climbing ability alongside its terrestrial bipedalism.23, 28

Little Foot

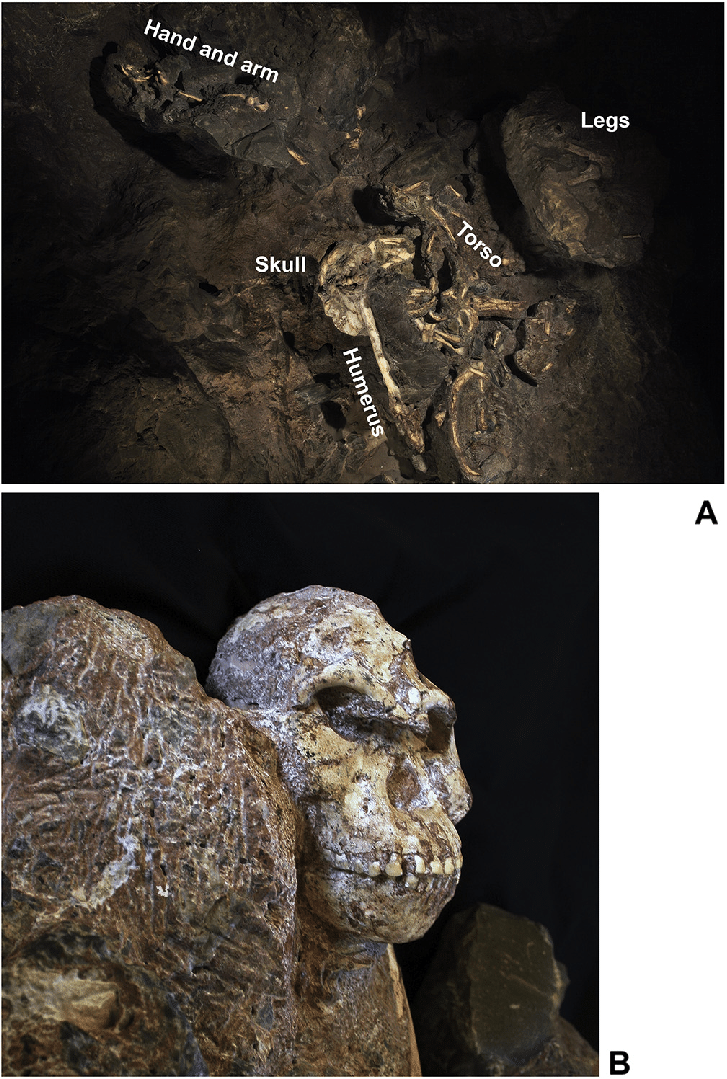

The story of StW 573, universally known as "Little Foot," is one of the most remarkable in the annals of fossil discovery. In 1994, paleoanthropologist Ron Clarke of the University of the Witwatersrand was sorting through boxes of animal fossils from Sterkfontein that had been collected from the Silberberg Grotto in the late 1970s and stored in the university's collections. Among the miscellaneous fragments, he identified four articulating foot bones of a hominin, including a first metatarsal that showed a combination of ape-like and human-like features.29 Clarke and Phillip Tobias announced the discovery in 1995, and Clarke recognized that the bones' clean breaks suggested that the rest of the skeleton might still be embedded in the cave breccia.29, 30

In 1997, Clarke dispatched two of his assistants, Stephen Motsumi and Nkwane Molefe, into the Silberberg Grotto armed with casts of the broken bone surfaces. Working by handheld lamp in the deep underground chamber, Motsumi and Molefe located the matching cross-section of a tibia protruding from the cave wall within just two days, a feat Clarke has described as one of the most remarkable in the history of paleoanthropology.30, 31 What followed was one of the longest and most painstaking excavations in the field's history. The skeleton was embedded in extremely hard calcified sediment (breccia), and Clarke insisted on extracting it by hand with small air scribes and chisels rather than using power tools or chemical dissolution, to avoid damaging the fragile bones. The excavation took more than twenty years, with the specimen not fully extracted, cleaned, and prepared until 2017.30, 31

The result was extraordinary: approximately 90% of the skeleton was recovered, making Little Foot the most complete Australopithecus skeleton ever found and one of the most complete early hominin fossils in existence.25 The skeleton belongs to an adult individual, probably female based on body size and pelvic morphology, who stood approximately 1.3 meters tall.25, 32 The cranial capacity is approximately 408 cc, small even by australopithecine standards.25 Dating of the specimen has been the subject of considerable debate; cosmogenic nuclide burial dating (using the radioactive decay of aluminum-26 and beryllium-10 produced by cosmic ray exposure of quartz) yielded an age of 3.67 million years, making Little Foot contemporaneous with Australopithecus afarensis in East Africa and significantly older than most of the A. africanus material from Sterkfontein Member 4.33, 34

The A. prometheus debate

The taxonomic assignment of Little Foot has become one of the most contested questions in current paleoanthropology. Clarke has consistently argued that StW 573 should not be classified as A. africanus but instead belongs to a separate species, Australopithecus prometheus, a name originally coined by Dart in 1948 for specimens from Makapansgat, another South African cave site, but later subsumed into A. africanus by most researchers.25, 35

Clarke and Kuman's 2019 detailed description of the Little Foot skull laid out the morphological case for the distinction. They argued that StW 573 differs from classic A. africanus (as represented by the Taung holotype and Sts 5) in several features: a flatter, more prognathic face; a more ape-like dental arcade shape; extremely heavy anterior dental wear unlike that seen in A. africanus but resembling the pattern in the older A. anamensis; and distinctive cranial vault proportions.25 Clarke identified a suite of Sterkfontein Member 4 and Makapansgat Member 3 specimens that he grouped with StW 573 as A. prometheus, distinct from a second group of specimens that he retained in A. africanus. Under this scheme, two different gracile australopithecine species coexisted in South Africa.25, 35

Not all researchers accept this interpretation. Many paleoanthropologists argue that the morphological variation Clarke attributes to species-level differences falls within the range of individual variation expected for a single sexually dimorphic species.22, 36 A 2025 study by Martin and colleagues in the American Journal of Biological Anthropology conducted a quantitative analysis of cranial shape and concluded that StW 573 does not fall outside the range of variation observed in A. africanus, and that its attribution to A. prometheus is not warranted by the available morphometric evidence.36 The debate remains unresolved, though its outcome has important implications for understanding australopithecine diversity and the evolutionary lineage leading to Homo.35

Key specimens

Major Australopithecus africanus specimens2, 21, 25

| Specimen | Date (Ma) | Site | Cranial capacity | Key significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taung Child (holotype) | ~2.8 | Taung | ~405 cc | First australopithecine; validated African human origins |

| Sts 5 ("Mrs. Ples") | ~2.5 | Sterkfontein | ~485 cc | Near-complete adult cranium; vindicated Dart |

| Sts 14 | ~2.5 | Sterkfontein | — | Partial skeleton with pelvis confirming bipedalism |

| Sts 71 | ~2.5 | Sterkfontein | ~428 cc | Adult cranium used in dimorphism studies |

| StW 505 | ~2.5 | Sterkfontein | ~560 cc | Largest known A. africanus cranium |

| StW 573 ("Little Foot") | 3.67 | Sterkfontein | ~408 cc | ~90% complete skeleton; A. prometheus debate |

| MLD 1 | ~2.6 | Makapansgat | — | Holotype of A. prometheus (Dart 1948) |

The Taung Child remains the holotype of the species, the single specimen against which all others are formally compared. Despite its juvenile status, it preserves critical diagnostic features: the forward-positioned foramen magnum, small canines beginning to erupt, a parabolic dental arcade, and the natural endocast that Dart used to argue for expanded association cortices.2, 9 The site of Taung itself has not yielded additional hominin material, leaving the Taung Child as the sole representative of A. africanus from that locality.7

Sts 5 ("Mrs. Ples") is the most iconic specimen after the Taung Child. The near-complete cranium lacks only the lower jaw and some teeth, and its excellent preservation has made it the basis for countless morphological studies. Recent CT-based analyses have revised its endocranial volume to approximately 485 cc.8, 21 Despite the nickname "Mrs.," several researchers now argue that the specimen is male, based on features such as the size of the mastoid process and overall cranial robusticity.22

Little Foot's completeness has provided unprecedented information about australopithecine postcranial anatomy. The skeleton includes a complete arm and hand, both legs and feet, much of the vertebral column, ribs, pelvis, and the skull with dentition.25, 32 Analysis of the limb proportions shows relatively long arms and relatively short legs compared to modern humans, consistent with a locomotor repertoire that combined habitual bipedalism with significant arboreal climbing.32 The hand shows curved phalanges suitable for grasping branches, while the foot, the feature that gave the specimen its nickname, displays a divergent big toe with some capacity for grasping, unlike the fully adducted hallux of modern humans.29

Evolutionary significance

Australopithecus africanus has long been considered a plausible ancestor or close relative of the genus Homo. In many phylogenetic analyses, it occupies a position between the earlier A. afarensis of East Africa and the earliest members of Homo, which appear in the fossil record around 2.8 to 2.3 million years ago.1, 37 Its combination of primitive features (small brain, arboreal limb proportions) with derived features (reduced canines, thick-enameled molars, committed bipedalism) exemplifies the mosaic pattern of evolution that characterizes the hominin lineage, where different anatomical systems evolved at different rates rather than in lockstep.23

The relationship between A. africanus and contemporary or near-contemporary species remains complex. In southern Africa, A. africanus overlapped temporally with the robust australopithecine Paranthropus robustus and possibly with early Homo.1, 17 If Clarke's taxonomic revision is accepted and Little Foot represents a distinct species A. prometheus, then australopithecine diversity in southern Africa was even greater than previously appreciated, with at least two gracile species present before the emergence of Paranthropus and Homo.25, 35

The broader significance of A. africanus extends beyond taxonomy. It was this species that first demonstrated a fundamental principle of human evolution: bipedalism preceded brain enlargement. Dart's insight, ridiculed in 1925, is now one of the most firmly established facts in paleoanthropology. The australopithecines walked upright for millions of years before the appearance of the larger-brained genus Homo, overturning the Victorian-era expectation that a large brain was the defining first step in becoming human.2, 13 The century-long arc from Dart's initial discovery to Clarke's meticulous excavation of Little Foot illustrates how the South African fossil record has repeatedly reshaped our understanding of human origins.38