Australopithecus afarensis is one of the best-known and most thoroughly documented species in the human fossil record. Formally named in 1978 by Donald Johanson, Tim White, and Yves Coppens, the species is represented by fossils from sites across East Africa spanning nearly a million years, from approximately 3.9 to 3.0 million years ago.1, 2 Its most celebrated specimen, the partial skeleton known as "Lucy" (AL 288-1), remains one of the most iconic discoveries in the history of paleoanthropology. Together with the Laetoli footprint trackways, the juvenile skeleton "Selam," and the large assemblage known as the "First Family," the A. afarensis fossil record paints a remarkably detailed portrait of a creature that walked upright on two legs but retained a small, ape-sized brain and features suited to life in the trees.3, 4

Discovery of Lucy

On 24 November 1974, American paleoanthropologist Donald Johanson and graduate student Tom Gray were surveying the badlands near the Hadar research camp in the Afar region of northeastern Ethiopia when Johanson spotted fragments of a hominin arm bone eroding from a slope. As they examined the area more closely, they found an occipital bone fragment, then pieces of femur, ribs, pelvis, and lower jaw, all clearly belonging to a single individual.3, 5 Over the following weeks, careful excavation recovered several hundred bone fragments that, when assembled, constituted approximately 40 percent of a single skeleton, an extraordinary level of completeness for a hominin fossil of this age.3

That evening, as the team celebrated their find at camp, the Beatles song "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" played repeatedly on a tape recorder. Someone suggested naming the skeleton "Lucy," and the name stuck, eventually becoming one of the most recognizable names in all of science.5, 6 In the Amharic language of Ethiopia, the specimen is known as "Dinkinesh," meaning "you are marvelous."6

Lucy stood roughly 107 centimeters (3 feet 6 inches) tall and weighed an estimated 29 kilograms (64 pounds).3, 7 Analysis of her dentition and the degree of epiphyseal fusion in her bones indicated she was a young adult at the time of death.3 Although her brain was small, her postcranial anatomy told a revolutionary story: the angled femur, broad ilium, and positioning of the femoral head demonstrated beyond reasonable doubt that Lucy walked upright habitually.7, 8

Naming the species

Although Lucy was found in Ethiopia, the holotype specimen of Australopithecus afarensis is actually LH 4, a mandible with nine teeth recovered by Mary Leakey's team in 1974 from the site of Laetoli in northern Tanzania.1, 9 When Johanson, White, and Coppens formally described and named the new species in 1978, they designated LH 4 as the type specimen because White had already fully described and illustrated it the previous year, and it satisfied the taxonomic requirement for a single diagnostic reference specimen.1 The species name afarensis refers to the Afar region of Ethiopia, where the majority of specimens, including Lucy, had been found.1

The decision to unite Tanzanian and Ethiopian fossils under a single species was controversial at the time. Some researchers, including Mary Leakey herself, objected to grouping the Laetoli and Hadar material together, arguing that the Laetoli specimens might represent a different taxon.9, 10 However, subsequent analyses of dental and cranial morphology supported the single-species interpretation, and A. afarensis is now widely accepted as a valid taxon spanning sites across eastern Africa.2, 10 The International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature later formally recognized LH 4 as the lectotype, settling the nomenclatural question definitively.9

The evidence for bipedalism

The most significant contribution of A. afarensis to our understanding of human evolution is the evidence it provides for early bipedalism. Before Lucy's discovery, many researchers assumed that large brains and bipedal locomotion evolved together. Lucy shattered this assumption: here was a creature with a brain scarcely larger than a chimpanzee's that nonetheless walked upright on two legs.7, 8

Several anatomical features of Lucy's skeleton point unambiguously to habitual bipedalism. Her femur angles inward from hip to knee, producing a "valgus knee" or bicondylar angle that positions the knees beneath the body's center of gravity during walking. This angle is characteristic of habitual bipeds and is absent in quadrupedal apes.8, 11 Her pelvis is short and broad, with laterally flaring ilia that anchor the gluteal muscles responsible for stabilizing the trunk during single-leg stance, a biomechanical requirement of bipedal walking that is unnecessary in quadrupeds.7, 12 The foramen magnum, the opening at the base of the skull through which the spinal cord passes, is positioned centrally beneath the skull rather than toward the back, indicating that the head was balanced atop an upright spine.2

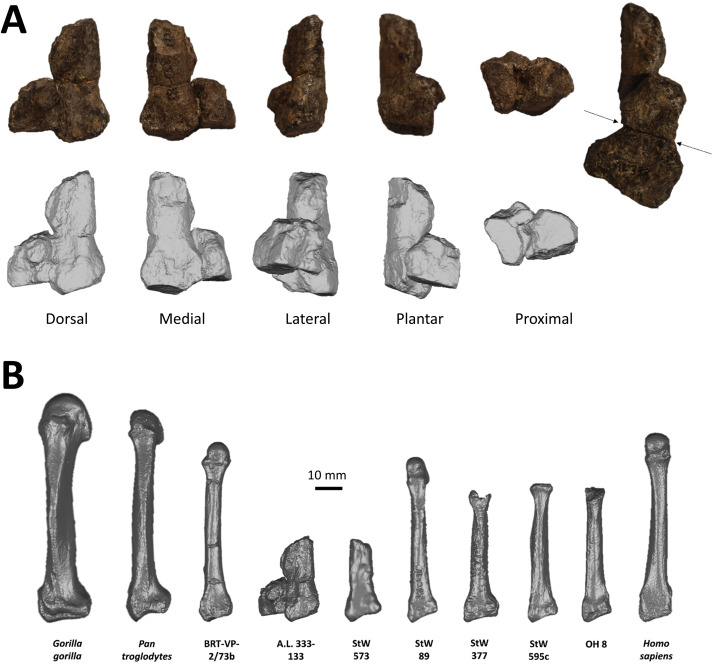

At the same time, A. afarensis retained features suggesting continued arboreal activity. Lucy's phalanges (finger and toe bones) are curved, a trait associated with grasping branches.3, 13 Her scapulae are cranially oriented, resembling those of climbing primates more than those of modern humans.4 This mosaic of bipedal and arboreal traits suggests that A. afarensis was a committed biped on the ground but likely still spent significant time in trees, perhaps for sleeping, feeding, or predator avoidance.13, 14

The Laetoli footprints

Perhaps the most dramatic evidence for A. afarensis bipedalism comes not from bones but from footprints. In 1978, Mary Leakey's team discovered a series of hominin footprint trails preserved in volcanic ash at Laetoli, Tanzania, dated to approximately 3.66 million years ago.15, 16 The prints were made when two or three individuals walked across a layer of wet volcanic tuff from the nearby Sadiman volcano, which subsequently hardened and was buried by additional ash layers, preserving the tracks in exquisite detail.15

The Laetoli footprints provide direct, unambiguous evidence of bipedal locomotion in a hominin living 3.66 million years ago. The prints show a well-developed longitudinal arch, a hallux (big toe) aligned with the other toes rather than divergent as in apes, and a heel-to-toe weight transfer pattern broadly consistent with modern human walking.16, 17 Biomechanical analysis by Crompton and colleagues demonstrated that the Laetoli hominins walked with an extended limb posture and weight distribution most similar to modern human bipedalism, though some studies have noted subtle differences suggesting a somewhat more flexed lower limb at foot strike than is typical in humans today.17, 18

Because A. afarensis is the only hominin species known from contemporaneous fossil deposits at Laetoli, the footprints are widely attributed to this species.15, 16 Additional hominin tracks discovered at Laetoli Site S in 2015 extended the evidence, revealing prints from two more bipedal individuals and providing data consistent with considerable body size variation within a single species.19 The Laetoli trackways remain the earliest undisputed direct evidence of bipedal locomotion in the hominin fossil record.16

Selam: the earliest child

In 2000, Ethiopian paleoanthropologist Zeresenay Alemseged discovered the fossilized remains of a juvenile A. afarensis in the Dikika research area of Ethiopia, in sediments dated to approximately 3.3 million years ago. The discovery was published in Nature in 2006 and immediately recognized as one of the most important hominin finds of the decade.4 Designated DIK-1-1 and nicknamed "Selam" (an Amharic word meaning "peace"), the specimen is the most complete juvenile hominin skeleton ever found from this period.4, 20

Dental development analysis indicated that Selam was approximately three years old at death and almost certainly female.4 The recovered skeleton comprises almost the entire skull, much of the torso, and substantial portions of the limbs. This extraordinary preservation allowed researchers to study aspects of A. afarensis anatomy that had never before been observable, particularly the development of the skull, hyoid bone, and scapula in a juvenile individual.4, 20

Selam's scapula is particularly informative. Its morphology is gorilla-like, with a cranially oriented glenoid fossa, reinforcing the interpretation that A. afarensis retained significant arboreal capabilities even as it walked bipedally on the ground.4, 21 The specimen also preserved a hyoid bone, the small bone in the throat that supports the tongue. Selam's hyoid more closely resembles those of African apes than of modern humans, providing indirect evidence about the vocal capabilities and throat anatomy of early hominins.22 Analysis of Selam's foot, published in 2018, revealed a medial cuneiform bone with features suited to grasping, suggesting that young A. afarensis children may have clung to their mothers much as young apes do today.23

The First Family

In 1975, just one year after discovering Lucy, Johanson's team found a concentration of hominin fossils at Hadar locality AL 333 that would become known as the "First Family." The site yielded over 216 hominin specimens representing a minimum of thirteen individuals, and possibly as many as seventeen, of varying ages and body sizes.24, 25 The fossils are dated to approximately 3.2 million years ago and were all recovered from a single geological stratum, strongly suggesting that the individuals died at roughly the same time in a single event.24

The cause of this group death remains debated. Hypotheses have included a flash flood, a predator attack, or a disease event, but the geological context most strongly supports a sudden catastrophic event such as flooding.24, 25 Regardless of the cause of death, the assemblage is profoundly important because it offers a snapshot of variation within a single population at a single moment in time. The fossils include individuals ranging from small-bodied (presumably female) to large-bodied (presumably male), providing crucial data for evaluating the degree of sexual dimorphism in the species.25, 26

The AL 333 assemblage also preserves evidence of foot anatomy that supports habitual bipedalism. The foot bones exhibit longitudinal and transverse arches, features essential for efficient bipedal walking and absent in the flat, flexible feet of extant great apes.14

AL 444-2: the complete skull

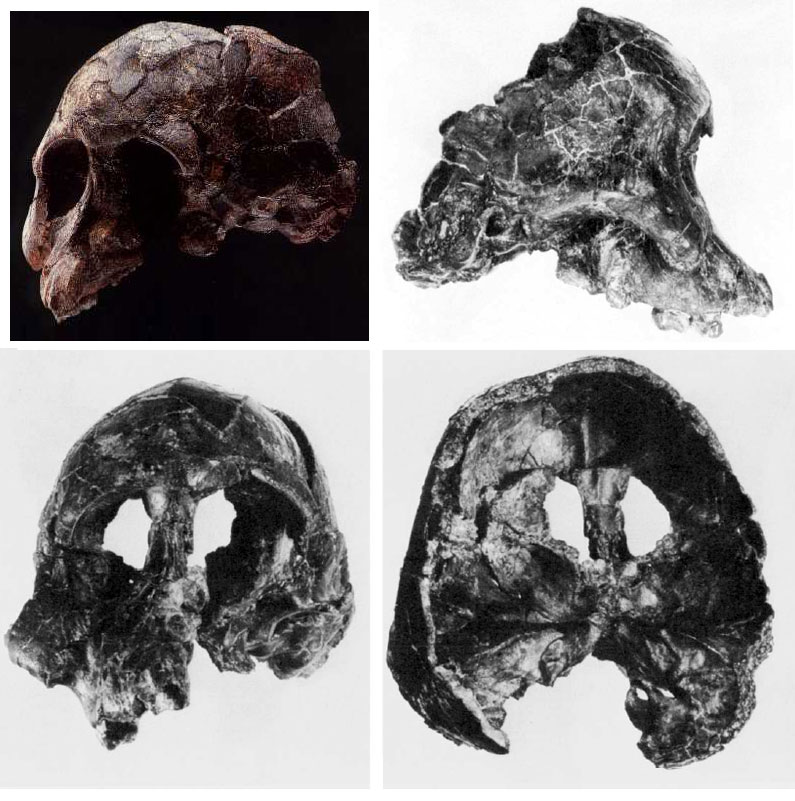

For nearly two decades after the species was named, no complete adult skull of A. afarensis was known. Cranial anatomy had to be inferred from fragmentary specimens and composite reconstructions, the accuracy of which was debated.27 This changed in 1992 when Yoel Rak discovered AL 444-2 at Hadar, a nearly complete adult male cranium dated to approximately 3.0 million years ago.27

Published by William Kimbel, Donald Johanson, and Yoel Rak in 1994, AL 444-2 confirmed several predictions about A. afarensis cranial morphology while settling debates that had persisted for years.27 The specimen has an estimated cranial capacity of 519 to 550 cubic centimeters, making it the largest known A. afarensis cranium and roughly the size of a modern chimpanzee brain, yet substantially smaller than the modern human average of approximately 1,400 cc.27, 28 The face is prognathic (forward-projecting), with large brow ridges, a flat nasal region, and a sagittal crest for the attachment of powerful chewing muscles.27

AL 444-2 was also significant because, as a large adult male, it could be compared directly to the smaller Lucy skeleton. The substantial size difference between the two specimens supported the hypothesis that A. afarensis exhibited marked sexual dimorphism, with males considerably larger than females.26, 27

Sexual dimorphism debate

The degree of sexual dimorphism in A. afarensis has been one of the most intensely debated topics in paleoanthropology. Some researchers have argued that the species exhibited gorilla-like levels of dimorphism, with males roughly 50 percent larger than females, which would imply a social structure involving male-male competition and possibly harem-based mating systems.10, 29 Others have contended that the dimorphism was more modest, comparable to that seen in modern humans, which would suggest different social dynamics.26

A landmark study by Reno and colleagues in 2003, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, used template method analysis and extensive simulations comparing A. afarensis postcranial remains with samples from modern humans, chimpanzees, and gorillas. The results indicated that skeletal size dimorphism in A. afarensis was most similar to that of contemporary Homo sapiens, not gorillas.26 A follow-up study in 2010 with an enlarged postcranial sample confirmed these findings.30

However, other analyses using different methodologies have reached different conclusions. Gordon and colleagues, examining the size distribution of A. afarensis fossils, argued for a higher level of dimorphism than Reno's team proposed.29 The debate hinges partly on which specimens are attributed to males versus females and on statistical methods for estimating dimorphism from fragmentary remains. What is not in dispute is that some degree of size variation existed: the small Lucy skeleton and the large AL 444-2 cranium, both securely attributed to A. afarensis, differ substantially in overall dimensions.26, 27

Brain and cognition

The cranial capacity of A. afarensis ranges from approximately 380 to 550 cubic centimeters across known specimens, with a mean of roughly 450 cc.28, 31 This places the species squarely within the range of modern chimpanzees (roughly 275 to 500 cc) and far below the modern human mean of approximately 1,400 cc.28 The relatively small brain of A. afarensis is significant precisely because the species was already a habitual biped: it demonstrates that bipedalism evolved before brain expansion, not alongside it.7, 8

Cranial capacity of key A. afarensis specimens (cc)28, 31

A 2020 study by Gunz and colleagues used CT scans of the Dikika child (Selam) and adult A. afarensis endocasts to investigate brain organization and growth patterns. They found that A. afarensis endocasts show an ape-like brain organization, without the derived features seen in later Homo species. However, the comparison between infant and adult endocasts suggested a prolonged period of brain growth relative to great apes, hinting at a life history pattern that was beginning to shift in a human-like direction.31

Key specimens

Major Australopithecus afarensis specimens2, 3, 4, 27

| Specimen | Date (Ma) | Site | Discovered | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LH 4 (holotype) | 3.65 | Laetoli, Tanzania | M. Leakey, 1974 | Adult mandible with 9 teeth; designated type specimen of the species |

| AL 288-1 "Lucy" | 3.2 | Hadar, Ethiopia | Johanson & Gray, 1974 | ~40% complete skeleton; 107 cm tall; angled femur and valgus knee prove bipedalism; curved phalanges indicate climbing |

| AL 333 "First Family" | 3.2 | Hadar, Ethiopia | Johanson team, 1975 | 216+ specimens from 13–17 individuals; group death event; demonstrates sexual dimorphism and foot arches |

| DIK-1-1 "Selam" | 3.3 | Dikika, Ethiopia | Alemseged, 2000 | Near-complete juvenile (~3 years old, female); gorilla-like scapula; hyoid bone preserved |

| AL 444-2 | 3.0 | Hadar, Ethiopia | Rak, 1992 | First complete adult skull; cranial capacity 519–550 cc; largest known A. afarensis cranium |

Beyond these major finds, numerous additional specimens have been recovered from Hadar and other sites. The Maka locality in the Middle Awash region of Ethiopia yielded a partial femur (MAK-VP-1/1) dated to approximately 3.4 million years ago, further extending the geographic and temporal range of the species.2 At Woranso-Mille, also in Ethiopia, fossils attributed to A. afarensis have been recovered from sediments as old as 3.8 million years ago, pushing the earliest appearance of the species close to 3.9 million years.32

Evolutionary significance

Australopithecus afarensis occupies a pivotal position in the human family tree. It is widely regarded as a plausible ancestor of later hominins, including both the "robust" australopiths (genus Paranthropus) and early members of the genus Homo.2, 10 Its temporal range of approximately 3.9 to 3.0 million years ago places it chronologically between earlier species such as Australopithecus anamensis (approximately 4.2 to 3.9 Ma) and later species such as Australopithecus africanus (approximately 3.3 to 2.1 Ma) and Australopithecus garhi (approximately 2.5 Ma).2, 33

A remarkable 2019 discovery by Haile-Selassie and colleagues complicated the picture of how A. afarensis related to its predecessors. A 3.8-million-year-old cranium of Australopithecus anamensis (MRD-VP-1/1) from Woranso-Mille demonstrated that A. anamensis and A. afarensis overlapped in time by at least 100,000 years, challenging the long-held assumption that A. anamensis simply evolved into A. afarensis through anagenesis (gradual transformation of one species into another without branching).33 Instead, the two species may have coexisted, with A. afarensis arising as a side branch from the A. anamensis lineage.33

The nearly 900,000-year timespan of A. afarensis is itself remarkable, indicating a highly successful species that persisted through substantial environmental changes in East Africa during the Pliocene epoch. Throughout this period, the species maintained its characteristic mosaic of bipedal and arboreal features, suggesting that this combination represented a stable and effective adaptive strategy for the woodland and savanna mosaic environments of Pliocene East Africa.2, 14

The legacy of A. afarensis extends beyond phylogenetics. The species fundamentally reshaped our understanding of human evolution by demonstrating that bipedalism, not brain enlargement, was the first major adaptation that set the hominin lineage apart from other African apes. When Lucy walked at Hadar 3.2 million years ago, her brain was one-third the size of ours, yet she walked upright. This single fact overturned decades of speculation and established a new framework for understanding how and why we became human.7, 8