For decades, the story of human evolution between the australopithecines and the genus Homo was presented as a relatively tidy progression: Australopithecus afarensis begat A. africanus, which begat early Homo. Discoveries made since the mid-1990s have thoroughly complicated this picture. Three species described between 1999 and 2015 — Australopithecus garhi, A. sediba, and A. deyiremeda — reveal that the later australopithecine period was characterized by remarkable diversity, with multiple species occupying overlapping habitats and exhibiting different combinations of primitive and derived features.1, 2, 3 Together, these species illuminate the complex, bushy nature of the hominin family tree during the critical interval when the lineage leading to Homo first emerged.

Australopithecus garhi: discovery and context

Australopithecus garhi was described in 1999 by Berhane Asfaw, Tim White, and colleagues based on a partial cranium (BOU-VP-12/130) recovered from the Hata Member of the Bouri Formation in the Middle Awash region of Ethiopia's Afar Depression.1 The species name garhi means "surprise" in the Afar language, reflecting the unexpected nature of the discovery.4 The holotype cranium was found by Ethiopian paleoanthropologist Yohannes Haile-Selassie on 20 November 1997, and its geological context places it at approximately 2.5 million years ago, a period that had been poorly represented in the hominin fossil record.1

The Bouri Formation sits along the western margin of the Middle Awash study area, an extraordinarily productive paleoanthropological region that has yielded hominin fossils spanning more than five million years.5 The Hata Member preserves a lakeside and river-margin environment, with sediments indicating shallow lake waters, floodplains, and gallery forests — a mosaic landscape that would have supported a range of plant and animal resources.6

Anatomy and tool use of A. garhi

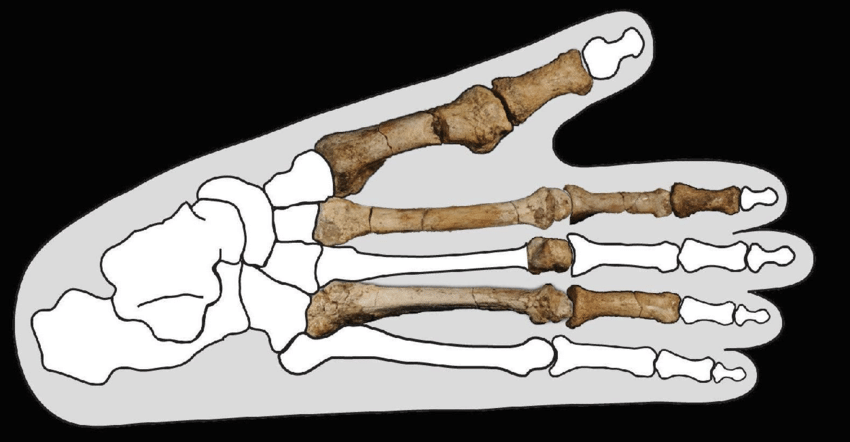

The cranium of A. garhi presents a combination of features that distinguishes it from all previously known australopithecines. Its estimated cranial capacity of approximately 450 cubic centimeters falls within the range of other australopithecines but at the upper end.1 The most distinctive feature is its dentition: A. garhi possesses extraordinarily large premolars and molars, with absolute tooth sizes exceeding those of A. afarensis, yet it lacks the heavy facial buttressing and sagittal cresting found in the robust australopithecines (Paranthropus).1, 4 This unusual combination of megadont teeth without robust cranial architecture suggested to the describers that A. garhi represents a lineage distinct from both the robust clade and the lineage leading to Homo.1

A partial skeleton (BOU-VP-12/1) found nearby but not definitively attributed to A. garhi preserves elements of the forearm and thigh. If it belongs to the same species, it suggests limb proportions in which the forearm remained relatively long (as in earlier australopithecines) while the femur had already elongated relative to the upper arm — a combination not seen in any other known hominin.1 This would imply that the elongation of the lower limb preceded the shortening of the forearm in hominin evolution, rather than both changes occurring simultaneously.

Perhaps the most significant aspect of the A. garhi discovery is its association with evidence of stone-tool-assisted butchery. In a companion paper published alongside the species description, Jean de Heinzelin and colleagues reported mammalian bones from the same stratigraphic level bearing unmistakable stone tool cut marks and percussion marks indicative of defleshing and marrow extraction.6 Antelope limb bones showed V-shaped incisions characteristic of cutting with sharp stone flakes, and long bones had been broken open in patterns consistent with deliberate marrow access.6 Although no stone tools were found in direct association with the bones at Bouri, Oldowan stone artifacts of similar age had been recovered at the nearby site of Gona.7 The temporal and spatial proximity of A. garhi to these butchered bones made it a candidate for the earliest hominin known to engage in tool-assisted meat processing, though the identity of the actual toolmaker remains uncertain because other hominin species may have been present in the region.1, 6

Australopithecus sediba: a boy's discovery

The story of Australopithecus sediba begins with one of paleoanthropology's most charming anecdotes. On 15 August 2008, nine-year-old Matthew Berger was exploring the grounds around the Malapa cave site in the Cradle of Humankind, South Africa, when he stumbled upon a brown rock containing a fossil clavicle.2 His father, paleoanthropologist Lee Berger of the University of the Witwatersrand, recognized the bone as hominin and initiated excavations that would yield two remarkably complete partial skeletons: MH1, a juvenile male that became the holotype, and MH2, an adult female.2 The species was formally announced in Science in April 2010, with the name sediba meaning "fountain" or "wellspring" in the Sotho language, reflecting Berger's hypothesis that this species might represent the wellspring of the genus Homo.2

The Malapa site preserves a remarkable taphonomic scenario. The two individuals appear to have fallen into a natural death trap — a deep shaft in the dolomitic cave system — and were subsequently buried rapidly by sediment, resulting in exceptional preservation.2 Uranium-lead dating of the flowstone capping the fossil-bearing sediments, combined with paleomagnetic analysis, places the specimens at approximately 1.977 million years ago.8 This date is significant because it falls after the earliest known appearance of Homo in the fossil record, a point that has fueled intense debate about whether A. sediba could truly be ancestral to Homo or represents instead a late-surviving australopithecine side branch.9

The mosaic anatomy of A. sediba

What makes A. sediba exceptional among fossil hominins is the degree to which it combines australopithecine and Homo-like features within a single body. A series of detailed anatomical studies published in Science in September 2011 documented this mosaic in remarkable detail across the brain, pelvis, hand, and foot.10, 11, 3, 12

The brain of MH1, studied through a high-resolution synchrotron endocast by Kristian Carlson and colleagues, revealed a cranial capacity of only about 420 cubic centimeters — firmly within the australopithecine range and comparable to a large grapefruit.10 Yet the shape of the frontal lobes showed subtle but important reorganization. Principal component analysis of the orbitofrontal region showed that MH1 aligned more closely with Homo endocasts than with other australopithecine specimens such as Sts 5 and Sts 60 from Sterkfontein.10 This finding suggested that neural reorganization in the frontal lobes may have preceded the dramatic brain size increase that characterizes the genus Homo, a possibility with profound implications for understanding how human cognitive abilities evolved.10

The pelvis of A. sediba, reconstructed by Job Kibii and colleagues from fragments of both MH1 and MH2, exhibited a suite of derived features suggestive of a more human-like mode of bipedal locomotion than that inferred for earlier australopithecines.11 The shape of the iliac blade and the orientation of the ischium indicated that A. sediba may have walked with a gait more similar to that of modern humans, even while retaining relatively long arms suited for climbing.11 Importantly, these pelvic changes occurred before significant increases in brain size, challenging the long-standing hypothesis that the human-like pelvis evolved primarily as an obstetric adaptation to accommodate larger-brained infants.11

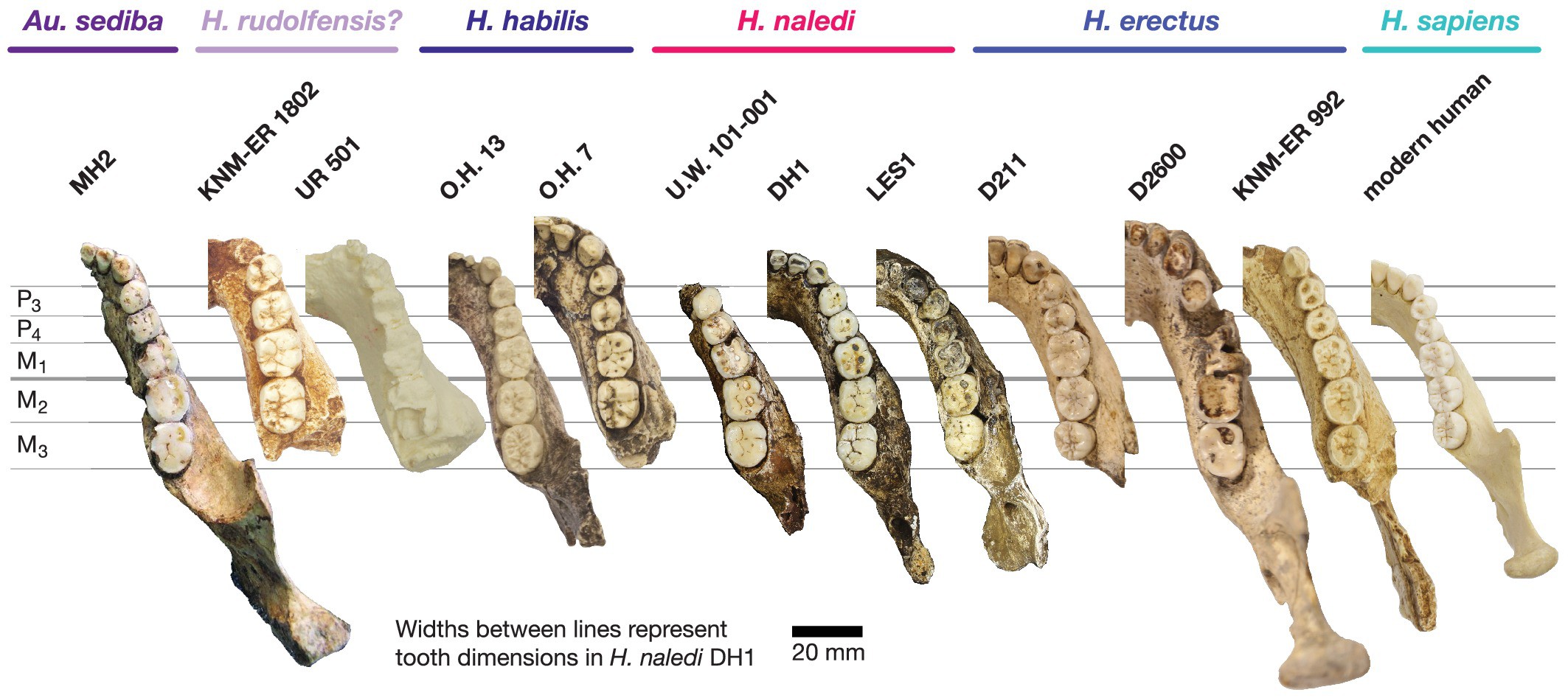

Perhaps the most celebrated element of A. sediba anatomy is the hand of MH2, described by Tracy Kivell and colleagues as the most complete hand known from any early hominin.3 The hand displays a remarkable combination: strong flexor muscles and curved finger bones associated with arboreal locomotion alongside a long thumb and short fingers that would have permitted a precision grip comparable to that of modern humans.3 Indeed, the thumb-to-finger ratio of A. sediba was more favorable for precision gripping than that of Homo habilis, the species whose name literally means "handy man."3, 13 Kivell and colleagues concluded that the A. sediba hand represented a better candidate for the ancestral condition from which the later Homo hand evolved, challenging the assumption that H. habilis was the first capable toolmaker.3

Mosaic features of Australopithecus sediba2, 10, 11, 3

| Anatomical region | Australopithecine-like features | Homo-like features |

|---|---|---|

| Brain | Small volume (~420 cc) | Reorganized frontal lobes |

| Dentition | Small teeth relative to body size | Reduced tooth size compared to earlier australopiths |

| Hand | Curved fingers, strong flexors for climbing | Long thumb, precision grip capability |

| Pelvis | Overall small body size | Reshaped ilium suggesting human-like gait |

| Lower limb | Relatively long arms | Femoral biomechanics approaching Homo |

The debate over A. sediba and Homo ancestry

Lee Berger and his collaborators have consistently argued that A. sediba is the best candidate for the ancestor of the genus Homo, or at least closely related to that ancestor.2, 14 They point to the species' unique combination of Homo-like features in the brain, pelvis, hand, and dentition as evidence that it occupies a phylogenetic position near the base of the Homo lineage. In a 2012 analysis, Berger and colleagues presented cladistic evidence placing A. sediba as a sister taxon to Homo, closer to early Homo than either A. africanus or A. afarensis.14

Critics have raised several objections. The most fundamental is chronological: the Malapa specimens date to approximately 1.98 million years ago, yet the earliest attributed Homo fossils, including a maxilla from Hadar (A.L. 666-1), date to approximately 2.33 million years ago.15 A species cannot be ancestral to a lineage that already existed several hundred thousand years before it. Berger and colleagues have responded that the known A. sediba specimens need not be the earliest members of their species and that older, undiscovered populations may well have existed in time to give rise to Homo.14

Other researchers have questioned whether A. sediba is a distinct species at all. Some paleoanthropologists consider it a chronospecies of A. africanus, arguing that the anatomical differences between the Malapa fossils and the Sterkfontein assemblage fall within the range of variation expected for a single evolving lineage over several hundred thousand years.9 Under this interpretation, the Malapa specimens represent a late-surviving population of A. africanus rather than a new species, making the fossils an interesting but phylogenetically marginal side branch. A 2016 study by Aureli and colleagues further questioned the evidence, arguing that the juvenile status of MH1 makes it unreliable for taxonomic and phylogenetic assessment because its cranial features may not reflect the adult morphology of the species.16

Despite these objections, the significance of the Malapa fossils is not seriously in doubt. Whether A. sediba is a direct ancestor of Homo, a close relative of that ancestor, or a late form of A. africanus, the specimens demonstrate conclusively that the transition from australopithecine to Homo-like anatomy was mosaic in nature, with different body systems evolving at different rates and in different sequences.14, 17

Australopithecus deyiremeda: coexistence in the Pliocene

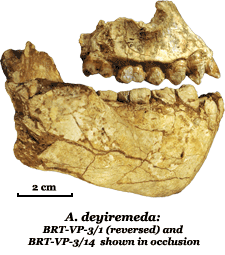

Australopithecus deyiremeda was described in 2015 by Yohannes Haile-Selassie and colleagues based on upper and lower jaw fragments recovered from the Burtele and Waytaleyta areas of the Woranso-Mille paleontological site in the Afar Region of Ethiopia.18 The species name, derived from the Afar words deyi ("close") and remeda ("relative"), reflects the discoverers' view that this species is a close relative of later hominins.18 Dated to between 3.3 and 3.5 million years ago, A. deyiremeda is contemporaneous with the famous A. afarensis, and its discovery provided the first compelling evidence that multiple hominin species coexisted within the same temporal and geographic range during the middle Pliocene.18

The holotype specimen, BRT-VP-3/1, is a partial maxilla preserving teeth that differ from A. afarensis in several respects: the anterior teeth are smaller, the canine and premolar morphology is more primitive, and the enamel thickness pattern differs.18 Haile-Selassie and colleagues argued that these differences exceed the range of variation seen within A. afarensis and justify recognition of a separate species.18 Not all researchers agree: some have suggested that the Woranso-Mille specimens might represent extreme variants within a highly variable A. afarensis population, a debate that echoes broader disagreements about how to delineate species boundaries among fossil hominins.19

A major breakthrough came in late 2025, when Haile-Selassie and colleagues published new postcranial remains of A. deyiremeda in Nature, including a partial foot that conclusively demonstrated differences in locomotion between this species and A. afarensis.20 The foot retained strong pedal grasping capabilities, with a divergent big toe more suited to arboreal locomotion than the relatively flat, human-like foot of A. afarensis.20 Carbon isotope analysis of dental enamel revealed that A. deyiremeda relied primarily on C3 foods from trees and shrubs, in contrast to the more mixed C3/C4 diet of A. afarensis.20 These findings provided direct evidence for ecological niche partitioning between the two species, explaining how they could coexist in the same landscape without being driven to extinction by competition.20

A diverse radiation, not a linear chain

The discovery of these three later australopithecine species, combined with earlier-known taxa like A. afarensis, A. africanus, and the robust Paranthropus lineage, paints a picture of the late Pliocene and early Pleistocene hominin landscape as far more diverse than was recognized even two decades ago. During the period from 3.5 to 2.0 million years ago, at least four and possibly six or more species of australopithecines were alive simultaneously in eastern and southern Africa.19, 21

Estimated cranial capacities of later australopithecines compared with related species1, 2, 22

This diversity has important implications for how we understand the origin of our own genus. The traditional model of a single australopithecine species gradually transforming into Homo has given way to a more complex scenario in which multiple lineages experimented with different adaptive strategies.21 Some, like Paranthropus, developed massive chewing apparatus for processing tough, low-quality plant foods. Others, like the lineage leading to Homo, invested in larger brains and stone tool technology. The later australopithecines described here appear to have been exploring various combinations of these strategies: A. garhi with its megadont teeth and apparent tool use, A. sediba with its human-like hand and brain reorganization but small overall brain size, and A. deyiremeda with its arboreal foot and specialized C3 diet.1, 2, 20

The recognition that our genus emerged from this diverse community of species rather than from a single ancestor-descendant chain represents one of the most significant conceptual shifts in paleoanthropology over the past quarter century. As Haile-Selassie and colleagues noted in their analysis of Pliocene hominin diversity, the question is no longer whether multiple species coexisted but how they partitioned the landscape ecologically and which among them gave rise to Homo.21

Key specimens

Key specimens of later Australopithecus species1, 2, 3, 18

| Specimen | Species | Age | Location | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BOU-VP-12/130 | A. garhi | 2.5 Ma | Bouri, Ethiopia | Holotype cranium; ~450 cc; associated with butchered bones |

| MH1 "Karabo" | A. sediba | 1.98 Ma | Malapa, South Africa | Juvenile holotype; ~420 cc; reorganized frontal lobes |

| MH2 | A. sediba | 1.98 Ma | Malapa, South Africa | Adult female; most complete early hominin hand; precision grip |

| BRT-VP-3/1 | A. deyiremeda | 3.4 Ma | Woranso-Mille, Ethiopia | Holotype maxilla; evidence of hominin coexistence in Pliocene |

Significance for human evolution

The later australopithecines collectively demonstrate several principles that are central to modern understanding of human evolution. First, they confirm that evolutionary change in hominins was mosaic rather than coordinated: different anatomical systems changed at different rates and in different sequences, with brain reorganization potentially preceding brain enlargement, pelvic changes preceding obstetric demands, and hand dexterity emerging before the sustained production of stone tools.10, 11, 3

Second, they demonstrate that the boundary between Australopithecus and Homo is not a sharp line but a zone of morphological overlap and experimentation. A. sediba possesses features that, found in isolation, would lead many paleoanthropologists to assign them to early Homo — yet the overall package remains more australopithecine than human.2, 14 This blurring of boundaries is exactly what evolutionary theory predicts: species do not transform instantaneously but through the gradual accumulation of changes across populations over hundreds of thousands of years.17

Third, the coexistence of multiple hominin species in the same landscapes at the same times demonstrates that hominin diversity was the norm throughout most of our evolutionary history, not the exception.18, 20, 21 The current situation, in which Homo sapiens is the sole surviving hominin species on the planet, is the anomaly — a state of affairs that has existed for fewer than 50,000 years out of the seven-million-year hominin record.23 The later australopithecines remind us that the path from our distant ancestors to our own species was neither straight nor solitary, but winding and crowded with evolutionary cousins.