The origin of the genus Homo is one of the most consequential and contested transitions in the human fossil record. Sometime between 2.5 and 2.0 million years ago, hominins in eastern Africa began to diverge from the australopith body plan, developing larger brains, smaller teeth, and a growing reliance on stone tools to process food.1 The first species assigned to this transition were Homo habilis, announced in 1964 by Louis Leakey, Phillip Tobias, and John Napier, and later Homo rudolfensis, formally named in 1986 by Valery Alexeev.2, 3 Together these two species occupy a critical but ambiguous position in the human family tree, sharing features with both the australopiths that preceded them and the Homo erectus populations that followed. Their fossils, scattered across sites in Tanzania, Kenya, Ethiopia, and possibly South Africa, tell the story of a lineage in flux — no longer quite Australopithecus, but not yet fully Homo in the modern adaptive sense.

Discovery and naming

The story of Homo habilis begins at Olduvai Gorge in northern Tanzania, one of the most productive paleoanthropological sites on Earth. In 1960, Jonathan Leakey, the son of Louis and Mary Leakey, discovered a set of fossils at site FLK NN that would be catalogued as OH 7. The remains consisted of a fragmentary mandible preserving thirteen teeth, two parietal bones from the cranial vault, and twenty-one hand and wrist bones, all belonging to a juvenile individual.2 Louis Leakey recognized that the specimen differed significantly from the robust australopiths already known from Olduvai and from the Australopithecus africanus material described from South Africa. The brain, as estimated from the parietal fragments, was substantially larger than anything seen in australopiths, and the hand bones suggested a capacity for precision gripping.2, 4

In 1964, Leakey, Tobias, and Napier formally described the new species in Nature, assigning it to the genus Homo and naming it habilis — a Latin word meaning "able, handy, mentally skillful, vigorous." The name was suggested by Raymond Dart, the discoverer of the Taung Child, and was chosen to reflect the apparent association between these fossils and the stone tools found at Olduvai.2, 5 The announcement was immediately controversial. Many paleoanthropologists, including the influential Sir Wilfrid Le Gros Clark, argued that the specimens fell within the range of variation of Australopithecus africanus and did not warrant a new species, let alone placement in Homo.6 The debate over where to draw the line between Australopithecus and Homo had begun, and it continues to this day.

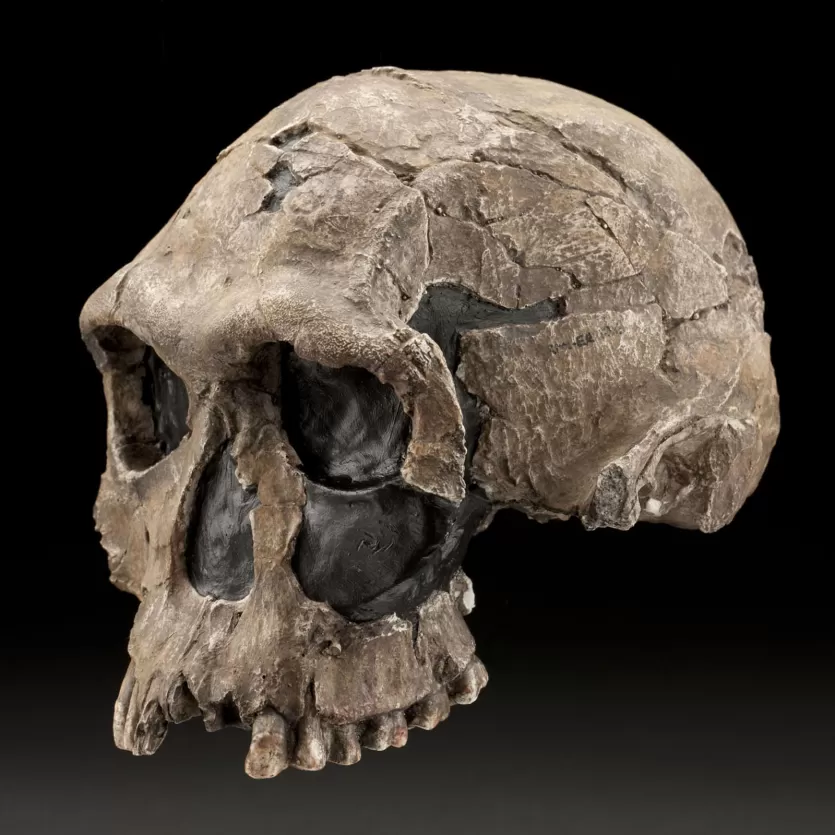

A decade later, a second major discovery would further complicate the picture. In 1972, Bernard Ngeneo, a member of Richard Leakey's field team at Koobi Fora on the eastern shore of Lake Turkana in Kenya, found a large, relatively complete cranium catalogued as KNM-ER 1470. Richard Leakey announced the find in Nature the following year, describing a skull with a cranial capacity of approximately 750 cubic centimeters — far larger than most H. habilis specimens — and a remarkably flat, orthognathic face unlike the more prognathic profile of the Olduvai material.7 Initially assigned to Homo sp. indet. (species indeterminate), the skull was eventually placed in its own species. In 1986, the Russian anthropologist Valery Alexeev erected the taxon Pithecanthropus rudolfensis for the specimen, named after Lake Rudolf, the colonial-era name for Lake Turkana. The genus was subsequently transferred to Homo by Colin Groves in 1989, yielding the name Homo rudolfensis as it is used today.3, 8

Key specimens

The fossil record of early Homo from the period between roughly 2.4 and 1.5 million years ago is modest in size but rich in morphological variation. Four specimens are particularly important for understanding the anatomy and diversity of H. habilis and H. rudolfensis.

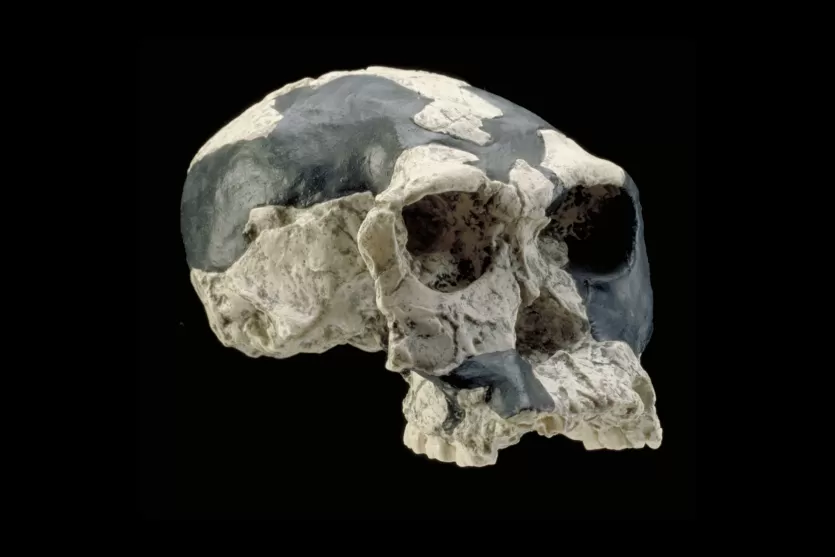

OH 7 ("Jonny's Child") remains the holotype — the defining specimen — of Homo habilis. Dated to approximately 1.78 million years ago, it was recovered from Bed I at Olduvai Gorge.2 A 2015 virtual reconstruction by Fred Spoor and colleagues used computed tomography to digitally reassemble the distorted mandible and parietal fragments. The reconstruction revealed a surprisingly primitive dental arcade, long and narrow in shape, more reminiscent of Australopithecus afarensis than of later Homo. Critically, the new endocranial volume estimate of 729 to 824 cubic centimeters was substantially larger than previous calculations, narrowing the gap between H. habilis and early H. erectus.9

OH 24 ("Twiggy"), discovered at Olduvai Gorge and dated to approximately 1.8 million years ago, is a heavily crushed but largely complete cranium. Despite its distortion — the nickname references the slender British model of the 1960s, as the skull was found flattened nearly flat — the specimen yields a cranial capacity estimate of roughly 590 cubic centimeters. OH 24 demonstrates that substantial variation in brain size existed within the H. habilis hypodigm, with some individuals possessing brains barely larger than those of large-brained australopiths.10

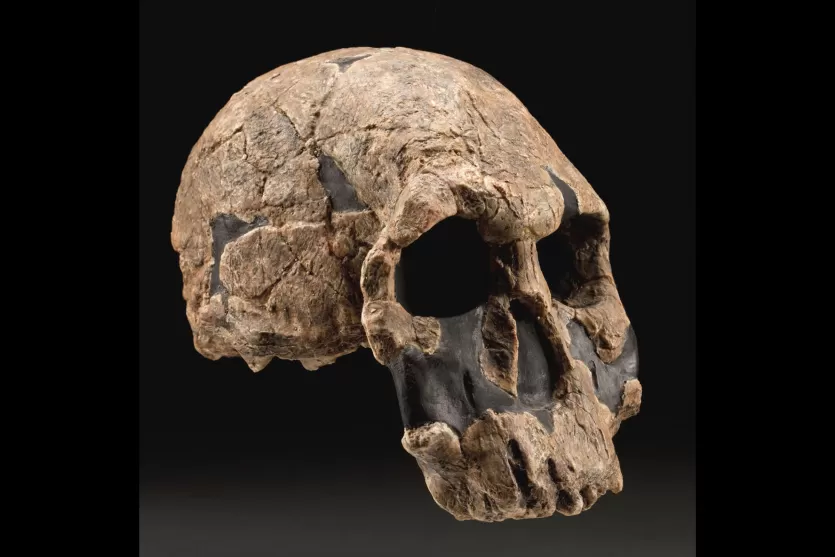

KNM-ER 1813, discovered at Koobi Fora in Kenya and dated to approximately 1.9 million years ago, is one of the smallest and most complete early Homo crania. With a cranial capacity of only 510 cubic centimeters, it falls within the upper range of australopith brain sizes, and its small face and gracile build have made it a focal point for debates about sexual dimorphism versus species diversity in early Homo.11 Some researchers have argued that KNM-ER 1813 is simply a small female H. habilis, while others contend that the morphological differences between it and larger specimens like KNM-ER 1470 are too great to be explained by sexual dimorphism alone and must reflect the presence of multiple species.12

KNM-ER 1470, the specimen that defines Homo rudolfensis, was found at Koobi Fora and dates to 1.95 million years ago. It preserves a nearly complete cranial vault and upper face, though the lower face and mandible are missing. The original reconstruction by Richard Leakey yielded a cranial capacity estimate of approximately 750 to 800 cubic centimeters, though a 2008 reanalysis by Timothy Bromage and colleagues revised this downward to roughly 700 cubic centimeters.7, 13 Even at the lower estimate, KNM-ER 1470 has a substantially larger brain than most H. habilis specimens, and its flat, broad face differs markedly from the more prognathic, smaller-faced morphology of OH 7 and KNM-ER 1813.9

Key early Homo specimens2, 7, 10, 11

| Specimen | Species | Age (Ma) | Site | Cranial capacity (cc) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OH 7 | H. habilis | 1.78 | Olduvai Gorge | 729–824 |

| OH 24 | H. habilis | ~1.8 | Olduvai Gorge | ~590 |

| KNM-ER 1813 | H. habilis | ~1.9 | Koobi Fora | 510 |

| KNM-ER 1470 | H. rudolfensis | 1.95 | Koobi Fora | ~752 |

Anatomy and morphology

The anatomy of H. habilis and H. rudolfensis is fundamentally mosaic, combining features associated with earlier australopiths alongside traits that foreshadow later Homo. In cranial anatomy, the most conspicuous derived feature is brain size. Australopiths such as A. afarensis and A. africanus typically had endocranial volumes between 400 and 530 cubic centimeters.14 By contrast, H. habilis specimens range from roughly 510 cc (KNM-ER 1813) to as high as 824 cc (OH 7 under the Spoor reconstruction), while H. rudolfensis as represented by KNM-ER 1470 falls in the range of 700 to 752 cc.9, 13 This represents a 30 to 80 percent increase over australopith averages, depending on which specimens and estimates are compared.

Cranial capacity comparison: australopiths and early Homo9, 14

Dental anatomy in both species is intermediate between australopiths and later Homo. The postcanine teeth (premolars and molars) are generally smaller than in australopiths but larger than in H. erectus, suggesting a diet that still included substantial amounts of hard or tough foods but was beginning to shift toward higher-quality resources, possibly aided by stone tool use for food processing.15 The 2015 reconstruction of OH 7 revealed that the mandibular dental arcade was long and narrow, a primitive configuration shared with A. afarensis, rather than the more parabolic (U-shaped) arcade seen in H. erectus and modern humans.9

The postcranial skeleton of H. habilis presents perhaps the most striking mosaic. The OH 7 hand bones preserve features consistent with both power gripping and precision manipulation, the latter being a hallmark of stone tool production.2, 4 However, the partial skeleton OH 62, discovered at Olduvai in 1986 by Tim White and Donald Johanson, revealed a surprisingly small-bodied individual — estimated at only about 100 centimeters tall — with relatively long arms and short legs, proportions more similar to A. afarensis than to H. erectus.16 This combination of a relatively large brain with australopith-like body proportions suggests that brain expansion and the shift to more human-like limb proportions did not occur simultaneously.

Habilis versus rudolfensis

The distinction between H. habilis and H. rudolfensis rests primarily on craniofacial morphology. The habilis morphotype, exemplified by OH 7, OH 24, and KNM-ER 1813, features a smaller brain (roughly 500 to 700 cc in the older estimates), a more rounded cranial vault, moderate prognathism (forward projection of the face), and relatively small postcanine teeth.9, 10, 11 The rudolfensis morphotype, represented primarily by KNM-ER 1470 and the subsequently discovered KNM-ER 62000 juvenile face, has a larger brain (700 to 800 cc), a broader and flatter face with less prognathism, and larger postcanine teeth with more complex root structures.7, 17

In 2012, Meave Leakey and colleagues published three new fossils from Koobi Fora dated between 1.78 and 1.95 million years ago: the juvenile partial face KNM-ER 62000, a complete mandible KNM-ER 60000, and a mandibular fragment KNM-ER 62003. The juvenile face KNM-ER 62000 shares the same flat, broad facial architecture as KNM-ER 1470 despite being much smaller, providing the strongest evidence to date that the rudolfensis morphology is not simply the male end of a single sexually dimorphic species but represents a genuinely distinct taxon.17 The mandible KNM-ER 60000, however, did not match either H. habilis or H. rudolfensis particularly well, hinting at the possibility that early Homo diversity may have been even greater than a simple two-species model suggests.17

Not all researchers accept the validity of H. rudolfensis as a separate species. Some argue that the morphological differences between KNM-ER 1470 and the habilis material can be explained by a combination of sexual dimorphism, individual variation, and the distortion of fossil specimens during preservation.12 Others have suggested that KNM-ER 1470 might be better placed in the genus Kenyanthropus, linking it to the earlier Kenyanthropus platyops from 3.5 million years ago, which shares the flat-faced morphology.18 The taxonomy of early Homo remains, as paleoanthropologist Bernard Wood has described it, "a mess," with the number of species recognized depending heavily on where individual researchers set the threshold for interspecific versus intraspecific variation.19

The Oldowan tool industry

The name Homo habilis — "handy man" — was chosen in large part because of the association between the fossils and stone tools at Olduvai Gorge. The Oldowan industry, named by Mary Leakey after Olduvai Gorge itself, represents the earliest well-documented tradition of deliberate stone tool production.20 Oldowan tools are characteristically simple: a knapper strikes a cobble (the core) with a hammerstone to detach sharp-edged flakes, which can then be used for cutting, scraping, or processing animal carcasses and plant materials. The cores themselves, with their rough chopping edges, were also used as tools.20

The oldest well-dated Oldowan assemblages come from Gona in the Afar region of Ethiopia, where Sileshi Semaw and colleagues recovered stone tools dated to approximately 2.5 to 2.6 million years ago. These artifacts display a surprisingly sophisticated control of stone fracture mechanics, indistinguishable in quality from much younger Oldowan assemblages.21 The temporal gap between these oldest Oldowan tools and the earliest H. habilis fossils (approximately 2.3 to 2.4 million years ago for the oldest attributed specimens) raised the possibility that Oldowan tools were initially produced by late australopiths rather than by members of the genus Homo.22

This question became even more pressing in 2015, when Sonia Harmand and colleagues announced the discovery of stone tools at Lomekwi 3 in West Turkana, Kenya, dated to 3.3 million years ago — predating the oldest Oldowan tools by 700,000 years and the earliest Homo fossils by nearly a million years.23 The Lomekwian tools are larger and more crudely made than Oldowan artifacts, but they demonstrate intentional knapping behavior. Their extreme age means they were almost certainly produced by australopiths, most likely Kenyanthropus platyops, the only hominin species known from the same area and time period.23 The implication is clear: stone tool manufacture is not a behavior unique to the genus Homo, and the name "handy man" reflects a historical assumption that has not held up under continued investigation.

Nevertheless, the Oldowan industry is strongly associated with the emergence and proliferation of early Homo. After 2.0 million years ago, Oldowan tools become dramatically more abundant at sites across eastern and southern Africa, coinciding with the appearance of H. habilis, H. rudolfensis, and early H. erectus.20, 22 Cut marks on animal bones found at Olduvai Gorge and Koobi Fora demonstrate that early Homo was using these tools to process meat, either through hunting or scavenging, adding animal protein and fat to a diet that had previously been predominantly plant-based.24

Does H. habilis belong in Homo?

The question of whether H. habilis genuinely belongs in the genus Homo has been debated since the species was first named in 1964, and the argument has grown more pointed over time. In 1999, Bernard Wood and Mark Collard published an influential paper in Science arguing that the genus Homo, as then constituted, was not a "good" genus by the standards of modern systematic biology. They proposed a revised definition of Homo based on adaptive strategy — specifically, body size, body proportions, locomotion, jaw and dental anatomy, and developmental pattern — and concluded that neither H. habilis nor H. rudolfensis met the criteria. Both species, they argued, were adaptively more similar to Australopithecus africanus than to Homo sapiens, and they recommended transferring both to Australopithecus.19

The Wood and Collard argument rested on several lines of evidence. First, the postcranial anatomy of H. habilis, as revealed by OH 62, showed australopith-like body proportions rather than the elongated legs and shortened arms characteristic of H. erectus and later Homo.16, 19 Second, dental development in H. habilis appeared to follow a more ape-like trajectory, with faster rates of dental maturation than those seen in H. erectus or modern humans.19 Third, the dietary adaptations inferred from tooth morphology and jaw mechanics placed H. habilis closer to the australopiths than to later Homo.15, 19 Under their revised criteria, the earliest species to qualify for the genus Homo was H. ergaster (or early African H. erectus), appearing in the fossil record at approximately 1.9 million years ago.19

Not all paleoanthropologists have accepted this reclassification. Proponents of retaining H. habilis in Homo point to the species' expanded brain size, its association with stone tools, and morphological features of the hand that indicate precision gripping — a key prerequisite for tool manufacture.4 The 2015 Spoor reconstruction of OH 7, which increased the estimated cranial capacity to 729–824 cc, further blurred the boundary between H. habilis and H. erectus in terms of brain size, undermining one of the clearest grounds for distinguishing the two.9 Others have argued that any genus-level boundary in a gradually evolving lineage is inherently arbitrary, and that the convention of placing these species in Homo has practical value even if the boundary is imprecise.1

The transition from Australopithecus to Homo

Regardless of how the taxonomic boundary is drawn, the fossil record documents a genuine adaptive shift occurring between 3.0 and 2.0 million years ago in eastern Africa. This period coincides with significant environmental change: the intensification of Northern Hemisphere glaciation around 2.8 million years ago drove a progressive aridification of the African climate, expanding grasslands at the expense of woodlands and forests.25 The environmental instability hypothesis, developed by Richard Potts and others, proposes that it was not aridity per se but the increasing variability of African environments during this period that selected for the cognitive flexibility, dietary breadth, and technological capacity that characterize the genus Homo.26

The earliest fossil attributed to Homo is a partial mandible from Ledi-Geraru in the Afar region of Ethiopia, designated LD 350-1, which dates to approximately 2.8 million years ago. The specimen combines a primitive, retreating chin with derived features of the molars and premolars that ally it with later Homo rather than with Australopithecus.27 If correctly attributed, it pushes the origin of the genus Homo back by approximately 400,000 years beyond the previously oldest known specimens, placing it squarely in the period of intensifying climatic variability. Stone tools from the same Ledi-Geraru area, dated to approximately 2.58 million years ago, may have been produced by the same population.28

The transition from Australopithecus to Homo was not a simple, linear replacement. Between 2.0 and 1.5 million years ago, at least three and possibly more hominin species coexisted in eastern Africa: H. habilis, H. rudolfensis, and H. erectus (or H. ergaster), alongside the robust australopiths Paranthropus boisei in the east and P. robustus in the south.1, 17 This pattern of multiple coexisting hominin species is now recognized as the norm rather than the exception for most of human evolutionary history, with the current situation — a single surviving hominin species — being the anomaly.29

Evolutionary significance

Homo habilis and Homo rudolfensis occupy a pivotal but ambiguous position in human evolution. They document the initial stages of the adaptive shift that would eventually produce modern humans: the expansion of brain size beyond australopith levels, the systematic manufacture and use of stone tools for food processing, and the beginnings of a dietary shift toward greater reliance on animal resources.1, 24 At the same time, their retention of primitive postcranial proportions, relatively rapid dental development, and small body size demonstrate that this transition was piecemeal rather than sudden, with different aspects of the "human package" evolving at different rates and in different combinations.16, 19

The ongoing taxonomic debate about these species is itself scientifically valuable, because it forces researchers to articulate what it means to be Homo — whether the genus should be defined by brain size, by tool use, by body proportions, by adaptive strategy, or by phylogenetic position.19, 1 There is no single correct answer, because genus-level boundaries in a continuously evolving lineage are always, to some degree, a human convention imposed on biological reality. What is not in dispute is the empirical evidence itself: the fossils from Olduvai Gorge, Koobi Fora, and other sites document a real and profound transformation in hominin biology and behavior that occurred in eastern Africa between 2.5 and 1.5 million years ago, regardless of what taxonomic labels we attach to the participants.