Homo erectus occupies a pivotal position in the story of human evolution. First identified from a skullcap found on the island of Java in 1891, it was the earliest hominin species recognized outside of Europe and the first fossil to be proposed as a direct ancestor of modern humans.1 Over the subsequent century and a half of discovery, H. erectus has proven to be one of the most geographically widespread and chronologically enduring species in the entire hominin fossil record, with specimens recovered from sites spanning eastern and southern Africa, the Caucasus, the Indian subcontinent, China, and Southeast Asia.2, 3 Its tenure on Earth lasted nearly two million years, from approximately 1.9 million years ago to as recently as 108,000 years ago, making it the longest-surviving member of the genus Homo.4, 5

The species is associated with a suite of evolutionary innovations that mark a decisive departure from the more ape-like australopithecines and early Homo species that preceded it. These include a substantial increase in brain size, the development of modern body proportions adapted for long-distance walking and running, the manufacture of Acheulean bifacial stone tools, and the earliest compelling evidence for the controlled use of fire.2, 6, 7 Taken together, the fossil, archaeological, and geological evidence for Homo erectus documents one of the most transformative chapters in human prehistory.

Dubois and the search for the "missing link"

The discovery of Homo erectus is inseparable from the ambition of Eugène Dubois, a Dutch anatomist who became the first scientist to conduct a deliberate field search for human ancestors. Inspired by Ernst Haeckel's hypothesis that a transitional form between apes and humans would be found in the tropics, Dubois enlisted as a military surgeon in the Royal Dutch East Indies Army in 1887 with the express purpose of finding fossil evidence of what Haeckel had named Pithecanthropus alalus, the hypothetical speechless ape-man.1, 8

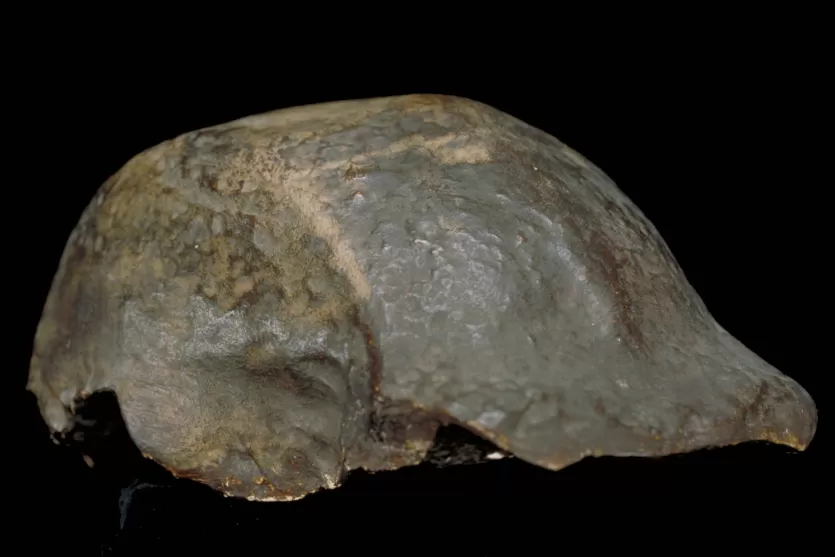

In 1891, Dubois's team excavated a mineralized skullcap (calvaria) from sediments along the Solo River near the village of Trinil in central Java. The specimen, catalogued as Trinil 2, displayed a combination of features that was genuinely unprecedented: a low, elongated braincase with a cranial capacity of approximately 900 cubic centimeters, prominent brow ridges, and a receding forehead, yet distinctly larger than any known ape.1, 9 A femur recovered nearby the following year appeared essentially modern in its morphology, suggesting fully upright bipedal locomotion. Dubois named the species Pithecanthropus erectus, meaning "upright ape-man," and argued that it represented the evolutionary intermediate between apes and humans.1

The reception was deeply divided. Within a decade, nearly eighty publications had appeared debating Dubois's interpretation. Some scholars dismissed the calvaria as that of a large gibbon; others classified it as a pathological modern human. Very few accepted Dubois's claim of a true intermediate form.8 Frustrated by the criticism and increasingly possessive of his discovery, Dubois eventually restricted access to the fossils for decades. It was not until the 1920s and 1930s, when remarkably similar fossils were unearthed at Zhoukoudian near Beijing, that the significance of the Java finds was fully appreciated.8, 10 In 1950, the taxonomist Ernst Mayr formally united "Java Man" and "Peking Man" under a single species within the human genus: Homo erectus.11

Peking Man and a wartime mystery

Between 1921 and 1937, excavations at Zhoukoudian (then romanized as Choukoutien), a limestone cave system roughly 50 kilometers southwest of Beijing, yielded one of the richest Homo erectus assemblages ever discovered. The site produced six partial crania, numerous cranial and postcranial fragments, and roughly 147 teeth, representing at least forty individuals.10, 12 The crania displayed the hallmark features of the species: thick vault bones, pronounced supraorbital tori, a sagittal keel, and cranial capacities ranging from approximately 850 to 1,225 cubic centimeters, with a mean near 1,029 cc.10, 13 The deposits were dated to approximately 770,000 years ago, placing the Zhoukoudian hominins firmly in the Middle Pleistocene.12

The German anatomist Franz Weidenreich, who directed research at the site from 1935, produced meticulous casts, drawings, and monographic descriptions of the fossils, a body of work that would prove irreplaceable.10 As war with Japan intensified in late 1941, Chinese and American scientists arranged to evacuate the original fossils to the United States for safekeeping. The bones were packed in two footlockers and entrusted to a detachment of U.S. Marines at Camp Holcomb near the port city of Qinhuangdao. They were last seen in early December 1941. On December 7, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor; on December 8, Japanese forces captured the Marine garrison. The fossils vanished and have never been recovered.12, 14

The loss is one of the most consequential in the history of paleoanthropology, but it did not erase the scientific record. Weidenreich's casts and exhaustive publications, particularly his 1943 monograph on the Zhoukoudian crania, preserved sufficient morphological data for continued study.10 Moreover, renewed excavations at the site after 1949 recovered additional hominin fragments, and the thick ash layers and thousands of stone artifacts at Zhoukoudian remain among the earliest archaeological evidence of habitual fire use, though the question of whether these represent controlled hearths or natural fires continues to be debated.12, 15

The Dmanisi revolution

No site has reshaped the understanding of early Homo erectus more profoundly than Dmanisi, a medieval town in the Republic of Georgia situated at the confluence of two rivers at an elevation of roughly 1,170 meters. Beginning in 1991, excavations beneath the ruins of a medieval fortress unearthed a series of hominin fossils dated to approximately 1.77 million years ago, making them the oldest known hominins outside of Africa by a substantial margin.16, 17

The site has produced five crania (designated Skulls 1 through 5), four mandibles, and extensive postcranial remains representing at least five individuals. What makes the assemblage extraordinary is not merely its age but the remarkable range of morphological variation it preserves. Cranial capacities span from just 546 cubic centimeters in Skull 5 (D4500) to roughly 730 cc in Skull 2 (D2282), a range that in any other context would almost certainly have led to the fossils being assigned to multiple species.16, 17

In 2013, David Lordkipanidze and colleagues published the description of Skull 5 (specimen D4500 with mandible D2600), the most complete adult skull of an early Pleistocene Homo ever recovered. Skull 5 combined a remarkably small braincase with a large, projecting face and massive jaw, a combination not previously documented in any single early Homo specimen. Through both traditional morphometric and geometric morphometric analyses, the authors demonstrated that the variation among the five Dmanisi crania was no greater than that observed among modern humans or among chimpanzees.16 Their conclusion was provocative: if the Dmanisi fossils, found at a single site of a single age, represented a single species, then the morphological differences used to distinguish Homo habilis, Homo rudolfensis, and Homo erectus in Africa might simply reflect normal variation within one evolving lineage.16, 18

Among the Dmanisi individuals, Skull 4 (D3444) is particularly remarkable for what it reveals about behavior. This elderly individual had lost all but one tooth well before death, with the alveolar bone extensively resorbed, indicating years of survival without the ability to chew food effectively. The specimen represents some of the earliest evidence of care for the elderly or disabled in the hominin fossil record, suggesting that these early humans lived in social groups capable of supporting individuals who could not fully provision themselves.19

The Dmanisi hominins were also associated with simple Oldowan-type stone tools rather than the more advanced Acheulean technology found at later H. erectus sites. This finding demonstrated that the first hominin dispersal out of Africa did not require large brains or sophisticated technology, only basic tool-making ability and the capacity for obligate bipedal locomotion.17, 20

Turkana Boy and the modern body plan

On a morning in August 1984, the Kenyan fossil hunter Kamoya Kimeu spotted a small fragment of hominin cranium eroding from a hillside near Nariokotome on the western shore of Lake Turkana. The subsequent excavation, led by Alan Walker and Richard Leakey, recovered 108 bones belonging to a single individual, catalogued as KNM-WT 15000 and popularly known as "Turkana Boy." It remains the most complete early hominin skeleton ever found.21, 22

Dated to approximately 1.55 million years ago, Turkana Boy died at an estimated age of eight to twelve years, yet already stood about 1.6 meters tall. Extrapolations of his growth trajectory suggest he would have reached an adult stature of approximately 1.85 meters, placing him within the range of modern human males.21, 23 His cranial capacity was approximately 880 cubic centimeters, which would likely have exceeded 900 cc at maturity.21

The skeleton's significance lies primarily in its body proportions. Unlike the short-legged, long-armed australopithecines, Turkana Boy had long legs relative to his arms, a narrow pelvis, and a barrel-shaped chest, a body plan fundamentally adapted for efficient striding bipedalism and thermoregulation in open tropical environments.22, 23 These proportions are strikingly similar to those of modern humans living in equatorial Africa and mark a decisive shift toward the body plan that would characterize all subsequent members of the genus Homo. The narrower pelvis, however, implies a smaller birth canal, which in turn suggests that H. erectus infants were born at an earlier stage of neurological development than australopithecine infants, requiring a longer period of postnatal brain growth and, by extension, greater parental investment.22, 24

Brain size through time

One of the most striking features of the Homo erectus fossil record is the progressive increase in cranial capacity over its nearly two-million-year span. The earliest specimens, particularly those from Dmanisi, have braincases as small as 546 cubic centimeters, only marginally larger than those of Homo habilis. By the Middle Pleistocene, however, H. erectus crania from both East Asia and Africa routinely exceed 1,000 cc, approaching the lower end of the modern human range.2, 13

Cranial capacity of selected Homo erectus specimens over time13, 16, 21

This trend is not a simple linear progression. At any given time slice there is substantial variation, and the smallest-brained specimens overlap with the largest H. habilis crania while the largest approach the modern human average of approximately 1,350 cc.2, 13 The overall pattern, however, is unmistakable: over the course of the species' existence, mean cranial capacity roughly doubled. This increase is associated with corresponding changes in diet, technology, and social complexity, though the precise causal relationships remain a subject of active investigation.24

Key Homo erectus specimens9, 16, 21

| Specimen | Date (Ma) | Location | Brain (cc) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dmanisi Skull 5 (D4500) | 1.77 | Georgia | 546 | Most complete early Homo skull; smallest brain |

| Dmanisi Skull 4 (D3444) | 1.77 | Georgia | — | Toothless elder; earliest evidence of care |

| KNM-WT 15000 | 1.55 | Kenya | 880 | Most complete early hominin skeleton |

| Sangiran 17 | 1.0 | Java | 1,004 | Large cranium from Southeast Asia |

| Trinil 2 (holotype) | ~0.9 | Java | ~900 | First recognized non-European hominin |

| Zhoukoudian crania | 0.77 | China | 850–1,225 | Six partial crania; evidence of fire use |

| Ngandong (Solo Man) | 0.11 | Java | ~1,251 | Last known H. erectus population |

Acheulean tools and the control of fire

The archaeological record associated with Homo erectus documents two of the most consequential technological innovations in human prehistory: the development of Acheulean bifacial tools and the controlled use of fire. Both mark a qualitative leap beyond the capabilities of earlier hominins and both appear to have enabled the species' expansion into new environments and latitudes.6, 7

The Acheulean stone tool industry, named after the site of Saint-Acheul in northern France, is characterized by large, symmetrically flaked bifaces, commonly referred to as hand axes. The earliest known Acheulean tools come from sites in the Turkana Basin of Kenya and Konso-Gardula in Ethiopia, where they have been dated to approximately 1.76 million years ago.6, 25 These implements required a substantially more complex reduction sequence than the simple Oldowan choppers and flakes that preceded them, demanding what cognitive scientists describe as hierarchical planning: the knapper had to hold a mental template of the desired final shape while executing a series of sequential, contingent removals from both faces of the core.6 The Acheulean tradition persisted for over 1.5 million years, making it by far the longest-lived tool technology in human history.25

The evidence for controlled fire use is more contested, but several sites have produced compelling data. At Wonderwerk Cave in South Africa, micromorphological analysis and Fourier transform infrared microspectroscopy identified burned bone fragments and ashed plant remains in Acheulean-bearing deposits dated to approximately one million years ago, representing the earliest secure evidence of burning within an archaeological context.7 At Gesher Benot Ya'aqov in Israel, dated to roughly 790,000 years ago, spatial analysis revealed discrete clusters of burned flint microartifacts and carbonized plant remains that are best explained by controlled hearths rather than natural wildfires.15 The Zhoukoudian cave deposits, dated to approximately 770,000 years ago, contain thick ash layers, burned bones, and charred seeds that were long cited as evidence of fire use by Peking Man, though recent reanalyses have questioned whether all of these deposits reflect hominin-controlled fires.10, 12

The mastery of fire would have had cascading consequences for H. erectus biology and behavior. Cooking renders food more digestible and increases the net caloric yield of both meat and tubers, potentially underwriting the metabolic costs of a larger brain. Fire also provided warmth, extending the habitable range into colder latitudes, and light, effectively lengthening the usable day. The Harvard primatologist Richard Wrangham has argued that the adoption of cooking was the single most transformative event in hominin evolution, fundamentally reshaping diet, anatomy, and social life.26

Global dispersal

No hominin before Homo erectus is known to have left Africa. The Dmanisi fossils, at 1.77 million years old, demonstrate that the first out-of-Africa dispersal occurred remarkably early, well before the appearance of Acheulean technology and with brains barely larger than those of Homo habilis.16, 17 What drove this expansion remains debated. Some researchers emphasize ecological factors, particularly the spread of open grassland habitats during the early Pleistocene, while others point to the dietary flexibility afforded by even rudimentary stone tools and meat consumption.20, 27

From the Caucasus, H. erectus populations spread both eastward and, potentially, westward. In East Asia, the oldest securely dated fossils are those from Sangiran and Mojokerto in Java, which have been dated to approximately 1.5 to 1.0 million years ago, with some researchers advocating dates as old as 1.8 million years for the Mojokerto child, though this remains controversial.3, 9 The Chinese fossil record includes not only the Zhoukoudian assemblage but also crania from Lantian (Gongwangling), dated to roughly 1.15 million years ago, and Hexian, dated to approximately 400,000 years ago.13 In Africa, H. erectus (often classified as H. ergaster when referring to African populations) is well represented at sites in Kenya, Ethiopia, Tanzania, and South Africa, with the Turkana Boy skeleton and the Daka calvaria from Ethiopia being among the most informative specimens.2, 21

The geographic range of H. erectus was truly extraordinary by the standards of any primate. From the highlands of Georgia at 1,170 meters elevation to the tropical lowlands of Java, from the seasonal woodlands of East Africa to the temperate deciduous forests of northern China, the species occupied a diversity of habitats that no earlier hominin had approached.2, 3 This ecological versatility reflects a species that had crossed a critical threshold in adaptive flexibility, relying on cultural solutions, tools, fire, and social cooperation, to buffer against environmental variation rather than depending solely on biological adaptation.27

Taxonomy and the lumper-splitter debate

Few questions in paleoanthropology have generated more sustained disagreement than the taxonomy of Homo erectus. The central issue is whether the fossils assigned to this species from across Africa, Europe, and Asia represent a single, geographically variable species or whether they are better divided into two or more distinct lineages. The debate has practical consequences: it determines how we understand the pattern and tempo of human evolution during the early and middle Pleistocene.2, 18

Many paleoanthropologists, particularly those working with African material, prefer to restrict the name Homo erectus to the Asian fossils (from Java and China) and to assign the earlier African specimens to a separate species, Homo ergaster. Under this scheme, H. ergaster is the ancestral African form that gave rise to H. erectus in Asia and to later species including H. heidelbergensis and ultimately H. sapiens in Africa.2, 24 Proponents of this split point to differences in cranial vault thickness, supraorbital morphology, and the degree of postcranial robusticity between African and Asian specimens.13

Other researchers, often described as "lumpers," argue that the variation between African and Asian populations falls within the range expected for a single widespread species and that splitting them creates taxonomic distinctions without clear biological meaning. The Dmanisi fossils have strengthened this position considerably. If the five Dmanisi crania, which span a range of variation as great as that separating H. habilis from African H. erectus, all belong to a single population, then the morphological grounds for maintaining multiple early Homo species are substantially weakened.16, 18

The last stand at Ngandong

The final chapter of Homo erectus was written on the island of Java. Between 1931 and 1933, Dutch geologists Oppenoorth and ter Haar recovered twelve calvaria and two tibiae from a bone bed roughly twenty meters above the Solo River near the village of Ngandong in Central Java. These specimens, collectively known as "Solo Man," represented the most anatomically advanced form of H. erectus, with cranial capacities reaching approximately 1,251 cc, the largest recorded for the species.5

For decades, the age of the Ngandong fossils was fiercely disputed, with published estimates ranging from over 500,000 to fewer than 50,000 years ago. In 2019, a comprehensive dating study led by Russell Ciochon and Kira Westaway resolved the controversy by applying Bayesian modelling to 52 radiometric age estimates from the bone bed, surrounding river terraces, and associated faunal remains. The resulting age of 117,000 to 108,000 years ago established that the Ngandong hominins were contemporaries of Homo sapiens, who by that time had already appeared in Africa and the Levant, and of Neanderthals, who occupied Europe and western Asia.5

The dating has profound implications. It means that Homo erectus persisted on Java for more than a million years after its first appearance there, long after the species had disappeared from Africa and the Asian mainland. This pattern of peripheral survival, sometimes called the "center-and-edge" model, is well documented in biogeography: populations at the margins of a species' range can persist long after the core populations have evolved into or been replaced by descendant species.5, 28 The Ngandong dates also raise the question of whether H. erectus and H. sapiens ever encountered each other in Southeast Asia. At present, the earliest evidence for modern humans in Java postdates the Ngandong fossils, but the margin is narrow enough that some temporal overlap cannot be excluded.5

Evolutionary significance

Homo erectus represents a watershed in human evolution. It was the first hominin to combine a large brain with a fully modern postcranial skeleton adapted for efficient long-distance locomotion. It was the first to manufacture stone tools requiring hierarchical planning. It was the first to control fire. And it was the first to leave Africa and colonize new continents.2, 6, 7, 16 In every meaningful sense, H. erectus established the biological and behavioral platform on which all subsequent human evolution was built.

The species' extraordinary temporal range, from roughly 1.9 million to 108,000 years ago, provides a unique window into the processes of evolutionary change over geological time. The progressive increase in brain size, the geographic expansion, the accumulating archaeological evidence of increasingly complex behavior, all unfold across a continuous fossil record that is among the best-documented of any hominin lineage.2, 5 The Dmanisi fossils demonstrate that the first dispersal out of Africa required neither large brains nor advanced tools, challenging earlier assumptions that a specific cognitive or technological threshold had to be crossed before hominins could leave the continent.16, 17

For debates about human evolution more broadly, the Homo erectus fossil record is significant because it documents gradual, mosaic evolution within a single lineage over nearly two million years. The variation within the species, from the tiny-brained Dmanisi individuals to the large-brained Ngandong crania, illustrates the kind of morphological diversity that evolution produces within a successful, widespread species. It provides a powerful empirical counterpoint to the claim that the human fossil record consists of disconnected, unrelated forms rather than an evolving continuum.16, 18