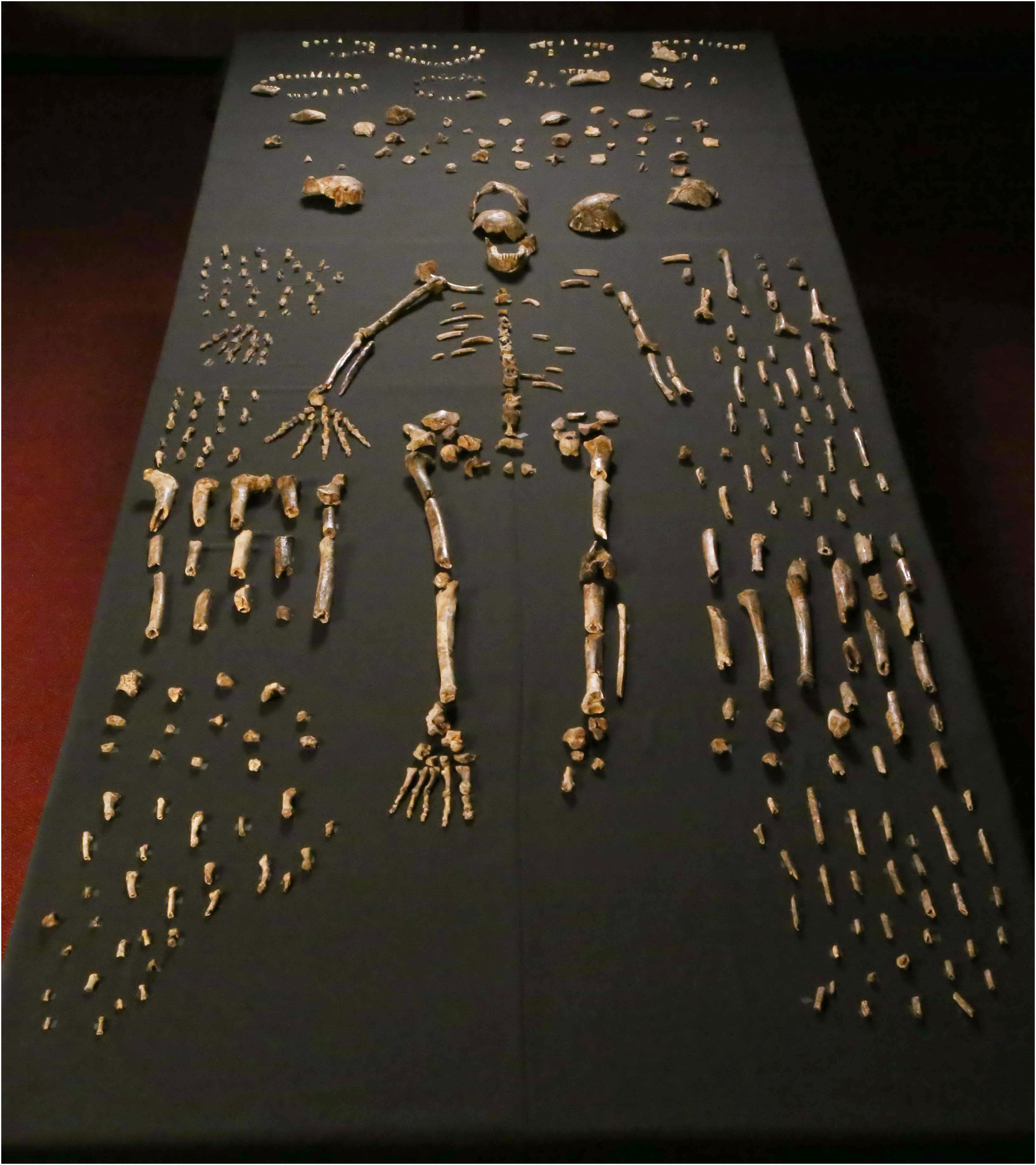

Homo naledi is a species of extinct hominin first described in 2015 from fossils recovered in the Dinaledi Chamber of the Rising Star cave system, located within the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site in Gauteng Province, South Africa.1 The species was named by a team led by paleoanthropologist Lee Berger of the University of the Witwatersrand, and the name "naledi" means "star" in the Sotho language, a reference to the Rising Star cave system where the fossils were found.1 With more than 1,550 numbered specimens representing at least 15 individuals, the Dinaledi assemblage constitutes the largest collection of a single hominin species ever discovered on the African continent.1, 2 The species is remarkable for combining an extremely small brain comparable to that of australopiths with a body plan that in many respects resembles later members of the genus Homo, creating a mosaic of primitive and derived features unlike any previously known hominin.1

The discovery

The story of Homo naledi's discovery reads like a caving adventure. In September 2013, recreational cavers Rick Hunter and Steven Tucker were exploring a little-known passage in the Rising Star cave system when they squeezed through a narrow chute approximately 18 centimeters wide, a gap so tight it became known as "Superman's Crawl" because it required one arm extended ahead and the other pinned against the body.2, 3 After navigating this passage and a 12-meter vertical climb known as the Dragon's Back, they dropped into a previously unexplored chamber roughly 30 meters below the surface.2 The floor was littered with bones. Hunter and Tucker photographed their find and brought the images to Lee Berger, who immediately recognized their significance.3

The extreme difficulty of accessing the Dinaledi Chamber presented an unusual logistical challenge. The narrow passages leading to the fossil deposit meant that most professional paleoanthropologists, accustomed to working in open-air sites or spacious caves, could not physically reach the bones. Berger issued an extraordinary call on social media: he needed scientists who were slender enough to fit through the 18-centimeter gap, skilled enough to excavate delicate fossils, and brave enough to work in a claustrophobic underground environment.3 Six researchers were selected, all of them women: Marina Elliott, Lindsay Eaves, Elen Feuerriegel, Alia Gurtov, Hannah Morris, and Becca Peixotto. They became known as the "underground astronauts," a name that captured both the isolation of their working conditions and the exploratory nature of the project.3, 4

The first excavation campaign, conducted in November 2013, lasted 21 days and recovered approximately 1,550 numbered fossil specimens.1 The material included cranial, dental, and postcranial elements from nearly every part of the skeleton, representing at least 15 individuals ranging from infants to elderly adults.1 The sheer volume of material was staggering by the standards of hominin paleontology, where a single jawbone or partial skull can form the basis of years of research. Here, in a single chamber, lay more hominin fossils than had been recovered from many famous sites over decades of work.1

Dating and geological context

When Homo naledi was first described in 2015, its age was unknown, and many researchers assumed it would prove to be very old, perhaps one to two million years, given its small brain size and certain primitive skeletal features.5 The dating results, published in 2017 by Paul Dirks, Eric Roberts, and colleagues, were therefore a profound surprise. Using a combination of uranium-thorium dating of flowstones overlying and underlying the fossils, electron spin resonance dating of three fossil teeth, and paleomagnetic analysis of cave sediments, the team established that the Dinaledi fossils date to between 236,000 and 335,000 years ago, placing them squarely in the Middle Pleistocene.5

This dating was conducted with extraordinary rigor. The most critical tests were performed at independent laboratories around the world, with each lab working without knowledge of the others' results to ensure reproducibility and eliminate bias.5 The convergence of multiple independent dating methods on the same age range gave the scientific community strong confidence in the result.5 The implications were remarkable: a hominin with a brain one-third the size of ours was alive at the same time as the earliest members of Homo sapiens, which most evidence suggests evolved between roughly 300,000 and 200,000 years ago in Africa.5, 6

The geological context of the Dinaledi Chamber is equally striking. The chamber lies deep within the Rising Star cave system, located in the Malmani dolomites approximately 800 meters southwest of the well-known site of Swartkrans.2 Detailed geological analysis by Dirks and colleagues revealed no evidence of a former, more accessible entrance to the chamber. The only known access route is the narrow chute through which Hunter and Tucker entered, suggesting that the chamber has been accessible only through this difficult passage for at least hundreds of thousands of years.2 No stone tools, no animal bones, and no evidence of predator or carnivore activity were found alongside the hominin remains, which is highly unusual for cave deposits containing hominin fossils.2

Anatomy and morphology

The anatomy of Homo naledi is a striking mosaic. Some features closely resemble those of modern humans and Neanderthals, while others are more similar to australopiths or early Homo species that lived millions of years earlier. This combination is not simply "intermediate" between apes and humans; rather, it represents a unique configuration of traits not seen in any other known hominin species.1

The skull of H. naledi is small, with endocranial volumes of approximately 465 cubic centimeters for smaller individuals (likely female) and 560 cubic centimeters for larger individuals (likely male) from the Dinaledi Chamber.7, 8 A near-complete cranium from the Lesedi Chamber, designated LES1, has an endocranial volume of approximately 610 cubic centimeters.9 These volumes overlap with those of australopiths and fall well below the range of Homo erectus (typically 600-1,100 cc), yet the overall shape of the skull is more Homo-like, with a relatively globular braincase and a less projecting face than australopiths.1, 8

Cranial capacity comparison across hominin species (cc)1, 8, 9

Despite this small brain, endocast analysis by Ralph Holloway and colleagues in 2018 revealed that H. naledi's brain was not simply a scaled-down version of an australopith brain. The frontal lobe showed a configuration more similar to that of Homo species, with features in the region of Broca's area (associated with language in modern humans) that distinguish it from australopiths.8 This finding suggests that changes in brain organization, not just brain size, may have been important in the evolution of the genus Homo.8

The hand of H. naledi, described by Tracey Kivell and colleagues from nearly 150 hand bones including a nearly complete adult right hand, presents its own mosaic pattern. The wrist bones and thumb display anatomy shared with Neanderthals and modern humans, suggesting a powerful precision grip and the potential ability to manufacture and use stone tools.10 Yet the fingers are more curved than those of most australopiths, indicating that the hand was regularly used for strong grasping during climbing and suspension in trees.10 This combination of tool-capable thumbs with climbing-adapted fingers had not been previously documented in any hominin species.10

The foot, described by William Harcourt-Smith and colleagues from 107 foot elements including a well-preserved adult right foot, is surprisingly modern. It shares many features with the human foot, including a well-developed arch and an adducted hallux (big toe aligned with the other toes), indicating it was well adapted for bipedal walking and standing.11 However, the toe bones are more curved than those of modern humans, suggesting some continued arboreal activity.11 The overall picture is of a hominin that walked upright on the ground in a manner broadly similar to modern humans but retained significant climbing ability.10, 11

The dentition of H. naledi is notably small and morphologically simple compared to other early Homo species. The molars lack the extensive crenulation, secondary fissures, and supernumerary cusps common in H. habilis, H. rudolfensis, and H. erectus.1, 12 This dental simplification, combined with the small overall tooth size, is more reminiscent of later Homo species than of the early members of the genus with which H. naledi shares its brain size.1

The Lesedi Chamber

In 2017, Hawks, Elliott, and colleagues announced the discovery of additional H. naledi fossils from a second chamber within the Rising Star cave system, designated the Lesedi Chamber (from the Setswana word for "light").9 The Lesedi Chamber is physically separated from the Dinaledi Chamber and represents an entirely independent depositional context for hominin remains.9 The discovery of the same species in two separate, difficult-to-access chambers within the same cave system significantly strengthened arguments about deliberate body deposition and demonstrated that the Dinaledi assemblage was not a one-off event.9

The Lesedi Chamber yielded 131 hominin specimens from at least three individuals, including both adult and immature material.9 The most significant specimen is a near-complete cranium of a large individual, designated LES1, which preserves much of the face, vault, and mandible. With an endocranial volume of approximately 610 cubic centimeters, LES1 represents the largest known H. naledi brain and extends the known range of variation within the species.9 The morphology of the Lesedi specimens is consistent with that of the Dinaledi sample, confirming their attribution to the same species and demonstrating a coherent pattern of anatomical variation.9

The body disposal hypothesis

One of the most provocative aspects of the Homo naledi story is the hypothesis that these small-brained hominins deliberately deposited their dead in the Dinaledi and Lesedi Chambers. The taphonomic evidence, the study of how the bones came to be preserved in their current location, presents a genuine puzzle. The Dinaledi Chamber contains no stone tools, no animal bones apart from a few owl bones and rodent remains near the surface, and no evidence of water transport, predator accumulation, or mass-death catastrophe.2 The only plausible access route requires navigating passages too narrow and too vertical for bodies to have been washed in by floodwaters or dragged in by carnivores.2

Berger and colleagues argued that the most parsimonious explanation for the assemblage is deliberate body disposal: members of H. naledi intentionally carried or dropped their dead into the chamber.1, 2 If correct, this would represent the earliest known evidence of such behavior in a hominin, and its occurrence in a species with a brain roughly the size of an orange would fundamentally challenge assumptions about the cognitive prerequisites for mortuary behavior.1

In 2023, the Rising Star team went further, publishing preprints in eLife claiming evidence of deliberate burial (not merely disposal) in the form of pit-like features in the cave floor, along with claims of rock engravings and possible fire use by H. naledi.13 These claims generated intense scientific controversy. Peer reviewers at eLife were unanimous in finding the evidence inadequate to support the conclusions. Reviewers noted insufficient analysis of how natural processes such as decomposition, sediment slumping, and erosion could explain the bone distributions, and criticized the lack of rigorous elimination of alternative hypotheses.13, 14

An independent study by Martinon-Torres and colleagues, published in the Journal of Human Evolution in 2023, found no scientific evidence supporting the claims that H. naledi buried their dead or produced rock art. When researchers attempted to replicate the geochemical analyses presented by the Rising Star team using standard protocols, they were unable to reproduce the reported results and found no evidence of soil mixing on the cave floor that would indicate deliberate digging.14 The extreme difficulty of accessing the fossil site has also limited independent verification, as no external experts have been invited to analyze the evidence in situ.14

The distinction between deliberate body disposal and deliberate burial is important. Many scientists accept that the taphonomic evidence is consistent with the bodies being intentionally placed in the chamber, as no other accumulation mechanism satisfactorily explains the assemblage.2 The more extraordinary claims of dug graves, symbolic engravings, and fire use, however, remain unsubstantiated and have not survived peer review in their current form.13, 14

Open access and the transformation of paleoanthropology

Lee Berger's approach to studying and publishing Homo naledi represented a deliberate challenge to the traditional culture of paleoanthropology, a field long characterized by restricted access to fossils, slow publication timelines, and intense competition between research groups. Berger chose to publish the initial description in eLife, a fully open-access journal, ensuring that the paper was freely available to anyone in the world from the moment of publication.1 He also made high-resolution three-dimensional scans of the fossils available for free download through the online repository MorphoSource, allowing researchers and educators worldwide to study and even print physical copies of the specimens.15

The excavations themselves were conducted with an emphasis on transparency. The Rising Star cave was wired with cameras and Wi-Fi, enabling live video feeds of the excavation to be broadcast online. Berger live-tweeted the progress of the dig, invited students from around the world to participate in virtual classroom sessions via National Geographic's Explorer Classroom program, and organized a large collaborative workshop to describe the fossils rather than restricting analysis to a small inner circle.3, 4 More than 50 researchers from over a dozen countries participated in the initial analysis.1

This open approach was not without its critics. Some paleoanthropologists expressed concern about the speed of publication, arguing that a find of this magnitude deserved years of careful analysis before formal description. Others questioned whether the collaborative workshop model could produce the same quality of scholarship as traditional, smaller-team analysis.6 Nevertheless, the H. naledi project demonstrated that rapid, open, and collaborative methods could yield rigorous scientific results and helped catalyze a broader movement toward open data sharing in paleoanthropology.15

Key specimens

Selected Homo naledi specimens1, 9

| Specimen | Chamber | Elements | Cranial capacity | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DH1 | Dinaledi | Partial calvaria + mandible | ~560 cc | Holotype specimen; defines the species |

| DH2 | Dinaledi | Partial cranium | ~560 cc | Second larger cranium, likely male |

| DH3 | Dinaledi | Partial cranium | ~465 cc | Smaller individual, likely female |

| DH4 | Dinaledi | Partial cranium | ~465 cc | Second smaller cranium, likely female |

| DH5 | Dinaledi | Partial cranium | — | Additional cranial material |

| LES1 | Lesedi | Near-complete cranium + postcrania | ~610 cc | Largest known H. naledi brain |

The DH1 specimen serves as the holotype, the single specimen that formally defines the species. It consists of a partial calvaria (the upper portion of the skull) and an associated mandible (lower jaw), recovered from the Dinaledi Chamber during the 2013 excavation.1 The cranial capacity of DH1 is approximately 560 cubic centimeters, placing it well within the range of australopiths but at the lower end of the genus Homo.1, 7 Despite this small size, the overall vault morphology, with its relatively thin walls and globular shape, is more consistent with Homo than with Australopithecus.1

The LES1 cranium from the Lesedi Chamber is the most complete skull yet recovered for the species. Its endocranial volume of approximately 610 cubic centimeters extends the known range of brain size variation in H. naledi and, combined with associated postcranial remains, provides the most comprehensive picture of a single H. naledi individual.9 The postcranial elements associated with LES1 confirm the mosaic pattern seen in the Dinaledi material: a combination of human-like and primitive features in a single individual.9

Evolutionary significance

Homo naledi has reshaped how paleoanthropologists think about human evolution. Its combination of a very small brain with an unexpectedly young geological age demolishes the notion of a steady, linear increase in brain size over time within the genus Homo.6 Here was a species with a brain barely larger than a chimpanzee's, living in southern Africa at the same time that early Homo sapiens were emerging in eastern and northern Africa with brains three times as large.5, 6

The phylogenetic position of H. naledi remains debated. Some analyses place it as an early-diverging member of the genus Homo, perhaps branching off near the base of the lineage close to Homo habilis.6 Others have suggested it could represent a late-surviving lineage that retained primitive features while other Homo lineages were evolving larger brains.16 The mosaic nature of its anatomy makes cladistic analysis challenging: depending on which characters are weighted most heavily, H. naledi can be placed in very different positions on the hominin family tree.16

What is clear is that H. naledi provides powerful evidence for the "bushy" model of human evolution, in which multiple hominin species coexisted across Africa (and beyond) at any given time, each adapted to its own ecological niche. The Middle Pleistocene of Africa, once thought to be dominated by the lineage leading to modern humans, now appears to have been home to a surprising diversity of hominin forms, including H. naledi in southern Africa, H. heidelbergensis or related forms in eastern and northern Africa, and early H. sapiens emerging among them.6, 16

The endocast studies of Holloway and colleagues added another dimension to this picture. Despite its small size, the H. naledi brain showed organizational features in the frontal lobe more similar to Homo than to australopiths, suggesting that brain reorganization and brain expansion may have been partly decoupled in hominin evolution.8 If H. naledi was indeed capable of the navigational planning required to repeatedly traverse a dark, narrow cave system to dispose of its dead, and capable of the social coordination such behavior implies, then brain size alone may be a poor proxy for cognitive capacity in hominins.8

The discovery also raises questions about the tempo of human evolution in Africa. The persistence of a small-brained hominin until at least 236,000 years ago suggests that Africa's complex geography, with its diverse habitats separated by deserts, forests, and mountain ranges, may have allowed distinct hominin populations to evolve in relative isolation for extended periods.16 Southern Africa's cave systems, in particular, may have served as refugia where archaic forms persisted long after their relatives elsewhere had evolved or gone extinct.6, 16