The question of when and where Homo sapiens first appeared has undergone a dramatic revision in the past decade. Until 2017, the conventional view held that our species originated in East Africa around 200,000 years ago, based primarily on the Omo Kibish and Herto fossils from Ethiopia.1, 2 The discovery that fossils from Jebel Irhoud in Morocco are approximately 315,000 years old pushed the origin of our species back by more than 100,000 years and shifted the geographic focus from a single East African "cradle" to the entire continent.3, 4 Today, the emerging consensus among paleoanthropologists is that Homo sapiens evolved not in one place but across a subdivided African population connected by intermittent gene flow, gradually assembling the suite of features we recognize as anatomically modern.5, 6

The Jebel Irhoud revolution

Jebel Irhoud is a cave site approximately 100 kilometres west of Marrakech, Morocco. Fossils were first recovered there in the 1960s during mining operations, but their significance was not fully appreciated for decades. The original finds, including the cranium Irhoud 1 and the mandible Irhoud 3, were initially dated to roughly 40,000 years ago and classified as African Neanderthals or archaic Homo sapiens.7 Renewed excavations led by Jean-Jacques Hublin of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, beginning in 2004, produced additional fossils representing at least five individuals, including cranial, mandibular, dental, and postcranial remains designated Irhoud 10 and Irhoud 11.3

The critical breakthrough came from redating the site. Daniel Richter and colleagues applied thermoluminescence dating to fire-heated flint artefacts found in direct association with the hominin fossils, yielding a weighted average age of 315 ± 34 thousand years ago.4 This result was corroborated by recalculated electron spin resonance dates on the Irhoud 3 mandible, which produced a combined uranium-series and electron spin resonance age of 286 ± 32 thousand years.4 Together, these dates placed the Jebel Irhoud hominins firmly in the early Middle Pleistocene, making them roughly 100,000 years older than any previously known Homo sapiens fossils.

The morphological analysis proved equally transformative. Hublin and colleagues demonstrated that the Jebel Irhoud faces are virtually indistinguishable from those of modern humans: short, retracted, and flat, with a modern-looking brow ridge and midface.3 The braincase, however, tells a different story. Rather than the globular shape characteristic of living humans, the Irhoud crania display an elongated, low vault more reminiscent of archaic Homo.3, 8 This combination of a modern face with an archaic braincase is precisely what a mosaic model of human evolution would predict: different anatomical regions evolving at different rates, with the face modernizing before the brain achieved its present configuration.8

Omo Kibish and the earliest unequivocal modern humans

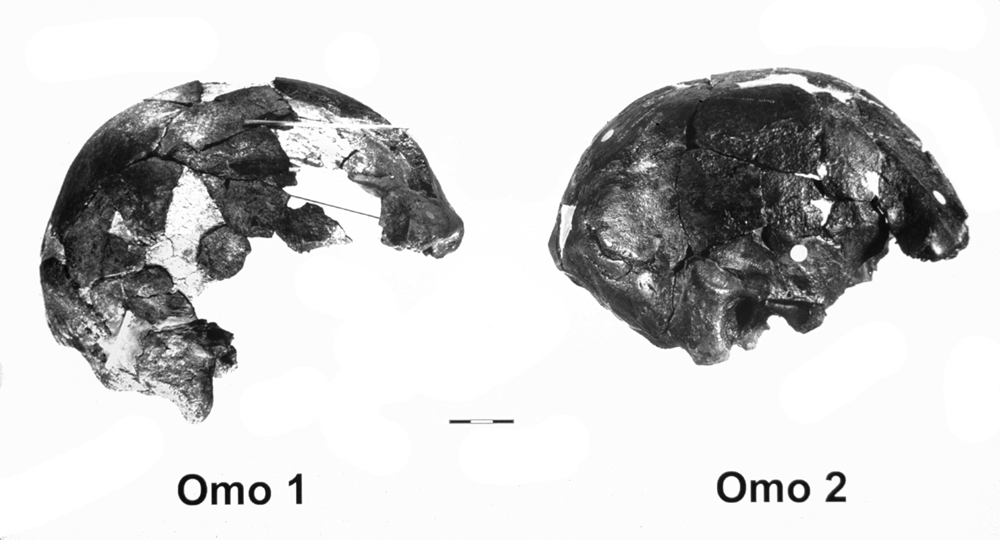

The Omo Kibish Formation in southwestern Ethiopia has yielded two of the most important early Homo sapiens specimens. Omo I and Omo II were discovered in 1967 by a team led by Richard Leakey along the Omo River, near the northern shore of Lake Turkana.9 The two specimens, found in the same geological member but at different localities approximately three kilometres apart, differ strikingly in their anatomy and have generated decades of debate about the range of variation within early Homo sapiens.10

Omo I possesses unambiguously modern human features: a high, globular cranial vault, a vertical forehead, reduced brow ridges, and a prominent chin.1, 10 Unlike the Jebel Irhoud specimens, which combine a modern face with an archaic braincase, Omo I displays fully modern morphology across both the face and the neurocranium. For this reason, it is widely considered the earliest definitive anatomically modern human from East Africa.1

Omo II presents a stark contrast. Its calvaria is longer and lower, with a more pronounced occipital torus and less globular profile, features that would not look out of place among earlier archaic humans.10 The coexistence of these two morphologically distinct individuals in the same geological formation and at roughly the same time has been interpreted as evidence that early Homo sapiens populations were far more variable than living humans, a finding consistent with the subdivided population model.11

The dating of Omo I has itself undergone significant revision. Initial argon-argon dates placed the fossils at approximately 195,000 years ago.12 In 2022, Celine Vidal and colleagues published a reassessment in Nature, linking the volcanic tuff directly overlying the Omo I horizon to a major eruption of Shala volcano in the Main Ethiopian Rift. Their geochemical correlation and argon-argon dating of the Shala eruption established a minimum age of approximately 233,000 years for Omo I, pushing the specimen back by nearly 40,000 years.1 This revised date narrows the chronological gap between Omo I and the Jebel Irhoud fossils, reinforcing the view that early Homo sapiens were widespread across Africa well before 200,000 years ago.

Herto and the evidence of early symbolic behaviour

In 1997, a team led by Tim White discovered three hominin crania in the Herto Member of the Bouri Formation in the Middle Awash region of Ethiopia. The primary specimen, BOU-VP-16/1, is a nearly complete adult cranium with an endocranial volume of approximately 1,450 cubic centimetres, well within the range of modern humans.2 Two additional crania were recovered: BOU-VP-16/2, another adult, and BOU-VP-16/5, a child aged six to seven years.2 Argon-argon dating of the volcanic deposits bracketing the fossils established an age between 160,000 and 154,000 years ago.2

White and colleagues classified the Herto specimens as a new subspecies, Homo sapiens idaltu (from the Afar word "idaltu" meaning "elder"), arguing that their morphology was intermediate between the more archaic features of specimens like Bodo and Kabwe and the fully modern anatomy of living humans.2 The BOU-VP-16/1 cranium displays a long, high vault, a broad face, and prominent but non-continuous brow ridges, features that fall within the upper range of modern human variation but retain subtle archaic qualities.2

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of the Herto finds is the evidence of deliberate postmortem modification. All three crania show cut marks made by stone tools, but the pattern of these marks differs from what is seen in cannibalism or butchery of animal remains. The adult crania display deep cut marks consistent with defleshing, but they also bear more superficial, repetitive scraping marks that suggest a deliberate, non-nutritive process.2 The child's cranium is particularly telling: its base was broken away and the broken edges polished smooth, while the sides of the skull exhibit a deep polish suggestive of repeated handling over time.2 White and colleagues interpreted these modifications as evidence of mortuary practice, potentially analogous to the skull curation documented in ethnographic contexts in New Guinea and elsewhere.2 If correct, this would represent some of the earliest evidence of symbolic or ritualistic behaviour in Homo sapiens, predating by tens of thousands of years the explosion of symbolic culture in the Upper Palaeolithic.13

Florisbad and the southern African record

The Florisbad skull was discovered in 1932 at a thermal spring site in the Free State province of South Africa. The specimen consists of a partial cranium preserving much of the right side of the face, the frontal bone, and part of the right parietal. Its endocranial volume has been estimated at approximately 1,400 cubic centimetres, overlapping with the modern human range.14

In 1996, Rainer Grun and colleagues applied electron spin resonance dating to a hominin molar from Florisbad, yielding an age of 259 ± 35 thousand years.14 This date places Florisbad in a temporal bracket similar to that of Jebel Irhoud and the revised age for Omo I, making it one of the oldest candidates for early Homo sapiens in southern Africa. The specimen's morphology reinforces its transitional status: it displays a broad, flat midface with reduced prognathism that anticipates the modern condition, combined with a thick, robust frontal bone and a supraorbital region that retains archaic features.14, 15

The taxonomic assignment of Florisbad has been debated. Some researchers have classified it as Homo helmei, a proposed species for African fossils that are transitional between Homo heidelbergensis and Homo sapiens.15 Others, including Chris Stringer, have argued that Florisbad, along with Jebel Irhoud and other middle Pleistocene African fossils, should be assigned to an early or archaic form of Homo sapiens.6 Regardless of the label, Florisbad's significance lies in demonstrating that populations with a mixture of modern and archaic features were present in southern Africa at roughly the same time that similar populations existed in Morocco and East Africa, consistent with the pan-African model of human origins.5

The gradual assembly of modern features

One of the most important insights from the early Homo sapiens fossil record is that anatomical modernity did not appear as a single package. Instead, different features of the modern human body plan emerged at different times and, potentially, in different populations across Africa. This pattern, known as mosaic evolution, is now considered a defining characteristic of how our species came into being.3, 8

The face appears to have modernized first. The Jebel Irhoud specimens, at 315,000 years old, already possess faces that fall within the range of modern human variation, with short, retracted midfaces and reduced prognathism.3 The braincase, by contrast, remained elongated and archaic for much longer. A landmark 2018 study by Simon Neubauer, Jean-Jacques Hublin, and Philipp Gunz used computed tomography scans of fossil and modern human crania to trace the evolution of brain shape within Homo sapiens. They found that the characteristic globular braincase of living humans, produced by expansion of the parietal lobes and the cerebellum, evolved gradually and did not reach its present form until sometime between 100,000 and 35,000 years ago.8 Crucially, this shape change occurred independently of brain size: even the oldest Homo sapiens fossils from Jebel Irhoud had endocranial volumes of around 1,400 millilitres, within the range of living humans.8

Timeline of key early Homo sapiens fossils in Africa1, 3, 14

This mosaic pattern extends beyond the skull. Postcranial remains from Jebel Irhoud include a partial femoral shaft that is robust by modern standards but within the range of variation seen in recent humans.3 Middle Pleistocene African limb bones in general tend to be more robust than those of living people, suggesting that body proportions, like brain shape, continued to evolve within Homo sapiens long after the species first appeared.6 The dental evidence tells a similar story: the Irhoud teeth are large compared to most modern human populations but fall within the overall range of Homo sapiens variation, and they share derived features such as simplified molar morphology that distinguish them from Homo heidelbergensis and other archaic species.3

The pan-African origin model

Before the Jebel Irhoud redating, the dominant model of human origins placed the cradle of Homo sapiens in East Africa, specifically in the Great Rift Valley of Ethiopia and Kenya. This "Garden of Eden" hypothesis was supported by the apparent concentration of the oldest modern human fossils in that region and by genetic studies suggesting that East African populations harbour the deepest branches of the human mitochondrial DNA phylogeny.16 The discovery that the oldest known Homo sapiens fossils come from the opposite end of the continent forced a fundamental rethinking of this model.3

Hublin and colleagues proposed a pan-African origin for our species, arguing that by 300,000 years ago, early Homo sapiens populations were dispersed across the entire African continent.3 This proposal was supported by the archaeological record: Middle Stone Age technology, the toolkit associated with early Homo sapiens, appears across Africa at roughly the same time, from Morocco to South Africa, suggesting continent-wide cultural connections or parallel innovation.4 The green Sahara hypothesis provides an environmental mechanism for this dispersal. During humid periods in the Pleistocene, the Sahara supported lakes, rivers, and savanna grasslands that would have permitted human populations to move freely between North Africa and the regions to the south.17

The pan-African model does not imply that a single, homogeneous population covered the continent. Rather, it envisions a network of semi-isolated populations, each evolving partly independently and partly in contact through intermittent gene flow.5 This demographic structure would explain the remarkable morphological diversity observed among early Homo sapiens fossils. Specimens of broadly similar age, such as the modern-looking Omo I and the more archaic Omo II, or the modern-faced but archaic-brained Jebel Irhoud crania, display a range of variation that far exceeds what is seen in any living human population.11

African multiregionalism

The idea that Homo sapiens evolved across a subdivided African population has been formalized as the "African multiregionalism" hypothesis. First articulated by Chris Stringer in 2014 and developed more fully by Eleanor Scerri and colleagues in a 2018 synthesis, this model proposes that the ancestral population of our species was fragmented across the continent by shifting ecological barriers, including deserts, forests, and fluctuating lake systems, that periodically isolated regional groups and then reconnected them.5, 6

Scerri and colleagues marshalled evidence from three domains to support this model.5 The fossil record shows that morphologically varied populations pertaining to the Homo sapiens lineage lived across Africa from at least 300,000 years ago, with no single region showing the "complete package" of modern features before others. The archaeological record demonstrates the polycentric origin of regionally distinct Middle Stone Age industries, suggesting that technological innovation was not radiating from a single source population. And genetic studies indicate that present-day population structure within Africa extends to deep times, with the San, Pygmy, and other populations diverging from each other well before 100,000 years ago.5, 18

A key prediction of this model is that modern human features should appear in a mosaic fashion, with different populations acquiring different modern traits at different times, and gene flow gradually spreading these traits across the continent. This is precisely what the fossil record shows. The modern face appears at Jebel Irhoud by 315,000 years ago; a modern-sized but non-globular braincase is present across multiple sites by 250,000 years ago; and the fully globular braincase does not become universal until sometime after 100,000 years ago.3, 8 As Scerri and colleagues put it, "all the features of the head that characterize contemporary humans do not appear together until fairly recently, between 100,000 and 40,000 years ago."5

Key specimens

Early Homo sapiens fossils in Africa1, 2, 3, 14

| Specimen | Age | Location | Key features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jebel Irhoud 1/10/11 | ~315 ka | Jebel Irhoud, Morocco | Modern face, archaic braincase; oldest known H. sapiens |

| Florisbad | ~259 ka | Free State, South Africa | ~1,400 cc; transitional face, robust frontal; supports multiregionalism |

| Omo I | ≥233 ka | Omo Kibish, Ethiopia | Fully modern vault and chin; earliest definitive AMH in East Africa |

| Omo II | ≥233 ka | Omo Kibish, Ethiopia | More archaic vault than Omo I; demonstrates early sapiens variation |

| Herto BOU-VP-16/1 | ~157 ka | Middle Awash, Ethiopia | ~1,450 cc; cut marks suggest mortuary practice; proposed H. s. idaltu |

Jebel Irhoud 1 is a partial cranium preserving much of the face and frontal bone. Its facial morphology is strikingly modern: the midface is short and retracted, the zygomatic bones are gracile, and the brow ridge, while continuous, is reduced compared to archaic forms like Homo heidelbergensis.3 The neurocranium, however, is long and low, lacking the parietal and cerebellar bulging that defines the modern globular braincase.3, 8 Irhoud 10, a partial cranium from the 2004 excavations, confirms these proportions and demonstrates that the mosaic morphology was not unique to a single individual but characteristic of the population.3 Irhoud 11, a juvenile mandible, adds further evidence of modern facial development at this early date.3

Omo I remains the gold standard for early anatomically modern humans. Its high, rounded vault, vertical forehead, and well-developed chin are features that would not be out of place in a modern human population.1, 10 The associated postcranial skeleton indicates a body plan broadly similar to that of tropical modern humans, with relatively long limbs and a narrow trunk.10 Omo II, by contrast, has often been described as "more primitive" than Omo I, with a longer, lower vault and a more prominent occipital torus.10 Some researchers have questioned whether both specimens should be assigned to Homo sapiens, but the consensus view treats Omo II as falling within the range of early sapiens variation, albeit at the archaic end of that range.11

The Herto cranium BOU-VP-16/1 is notable for its large size (approximately 1,450 cubic centimetres) and its morphological position between archaic African forms and fully modern humans.2 White and colleagues argued that this intermediate position, combined with the 160,000-year date, made Herto an ideal candidate for a direct ancestor of living humans, and they designated it the type specimen of a new subspecies, Homo sapiens idaltu.2 Not all researchers have accepted this subspecific distinction; some argue that the Herto morphology falls within the range of variation of a single, variable species.6

Genetic corroboration

The fossil-based pan-African model has received strong support from genomic studies. Analyses of present-day African genetic diversity consistently reveal deep population structure extending back to the Middle Pleistocene. A 2017 study by Schlebusch and colleagues sequenced the genomes of southern African KhoeSan individuals and estimated that the deepest divergence within the human lineage, between the San and other African populations, occurred between 260,000 and 350,000 years ago, a date strikingly consistent with the age of the earliest Homo sapiens fossils.18

Ancient DNA has provided additional insights where it is available. While DNA preservation in Middle Pleistocene African fossils remains extremely poor due to tropical conditions, studies of more recent ancient genomes have revealed complex patterns of admixture and population structure within Africa that are consistent with the multiregional model.19 Ragsdale and colleagues developed a computational model in 2023 that tested the genetic evidence against various demographic scenarios and found that the best fit involved at least two ancestral populations, weakly connected by gene flow, that merged to form modern Homo sapiens over an extended period.20 This result challenges the notion of a single founding population and supports the idea that our species emerged from the interaction of multiple African lineages.

Furthermore, Durvasula and Sankararaman identified signals of introgression from archaic, as-yet-unidentified hominin lineages into the genomes of present-day West African populations, suggesting that the story of human origins involved not only interbreeding between subdivided sapiens populations but also gene flow from more distantly related archaic hominins within Africa.21 This "ghost introgression" adds another layer of complexity to the African multiregionalism model and parallels the well-documented interbreeding between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals outside Africa.22

Significance for understanding human origins

The early Homo sapiens fossil record in Africa has fundamentally changed how paleoanthropologists understand the origin of our species. Three major shifts stand out. First, the origin of Homo sapiens is now dated to at least 300,000 years ago, not 200,000 years ago as was commonly stated until the mid-2010s.3, 4 Second, there is no single "birthplace" of humanity; the evidence points to a continent-wide process involving multiple regions of Africa simultaneously.3, 5 Third, anatomical modernity was not an event but a process, a gradual accumulation of modern features over hundreds of thousands of years, with different traits appearing at different times and in different populations.8

These insights have practical implications for how we define our species. If there was no single moment or place where Homo sapiens "appeared," then drawing a sharp line between our species and its immediate ancestors becomes inherently arbitrary. The Jebel Irhoud fossils, with their modern faces and archaic braincases, illustrate this boundary problem acutely: they are clearly on the sapiens lineage, but they do not look like living humans.3 Similarly, the morphological gap between Omo I and Omo II, two roughly contemporaneous fossils, underscores the diversity within early human populations and the difficulty of using any single feature as a species-defining criterion.11

The emerging picture is one of deep complexity. Homo sapiens evolved not through a simple linear progression in one corner of Africa but through a continent-wide process of divergence, intermittent reconnection, and gradual morphological integration. The fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Omo Kibish, Herto, and Florisbad are windows into different moments and different places in this process, each preserving a slightly different snapshot of an evolving, geographically dispersed species. Taken together, they constitute some of the most compelling evidence in the entire human fossil record for the evolutionary origin of our kind.5, 6