Homo neanderthalensis is the best-documented extinct human species in the fossil record. Hundreds of specimens spanning more than 300,000 years have been recovered from sites across Europe, the Middle East, and Central Asia, providing an extraordinarily detailed picture of Neanderthal anatomy, genetics, behavior, and ecology.1 The species takes its name from the Neander Valley near Düsseldorf, Germany, where quarry workers unearthed a partial skeleton in 1856 — just three years before the publication of Darwin's On the Origin of Species.2 That discovery launched more than a century and a half of research that has fundamentally reshaped our understanding of what it means to be human.

For much of the twentieth century, Neanderthals were depicted as dim-witted brutes, stooped and shuffling, the evolutionary dead end of a lineage that could not compete with clever Homo sapiens. This caricature owes much to an influential but deeply flawed reconstruction published by the French paleontologist Marcellin Boule in 1911–1913, based on a single elderly individual riddled with arthritis.3 Modern research has dismantled that image entirely. Neanderthals had brains at least as large as ours, fashioned sophisticated stone tools, controlled fire, buried their dead, cared for the disabled, adorned themselves with pigments and feathers, and — most remarkably — interbred with our own species, leaving a genetic legacy that persists in billions of people today.4, 5

Discovery and recognition

The first Neanderthal fossil to enter the scientific record was not the Feldhofer specimen but a skull from Forbes' Quarry, Gibraltar, discovered by Lieutenant Edmund Flint in 1848.6 The significance of this cranium, now designated Gibraltar 1, was not appreciated at the time, and it sat unstudied for years. When George Busk finally described it for the scientific community in 1865, the Feldhofer find had already seized the spotlight.6

The Feldhofer 1 calvaria and postcranial bones were recovered from a limestone cave in August 1856 by quarry workers who passed them to the local schoolteacher and naturalist Johann Carl Fuhlrott. Fuhlrott recognized the bones as ancient and unusual, and brought them to the anatomist Hermann Schaaffhausen, who presented them to the scientific community in 1857.2 The robust brow ridges and thick limb bones provoked fierce debate. The pathologist Rudolf Virchow dismissed the skeleton as a modern human deformed by disease, while Thomas Huxley recognized it as a primitive but genuinely human form.1 The Irish geologist William King formally named the species Homo neanderthalensis in 1864, making it the first fossil hominin species to be given a scientific name.1

Interdisciplinary reinvestigation of the Feldhofer site in 1997–2000 recovered more than 60 additional skeletal fragments from the cave sediment, including pieces that physically refit to the original 1856 skeleton. Radiocarbon dating placed both the original specimen and a second individual at approximately 40,000 years before present, and mitochondrial DNA was successfully extracted — making Feldhofer 1 the first Neanderthal to yield ancient genetic material.2

Anatomy and cold adaptation

Neanderthal anatomy reflects hundreds of thousands of years of adaptation to the glacial climates of Pleistocene Europe. Their bodies were short and stocky, with barrel-shaped chests and shortened distal limb segments — proportions that reduce surface area relative to body mass and conserve heat, following the ecogeographic principles described by Bergmann's and Allen's rules.7 Average male stature is estimated at around 164–168 centimeters, with body mass in the range of 76–83 kilograms, significantly heavier than contemporaneous Homo sapiens of similar height.7, 1

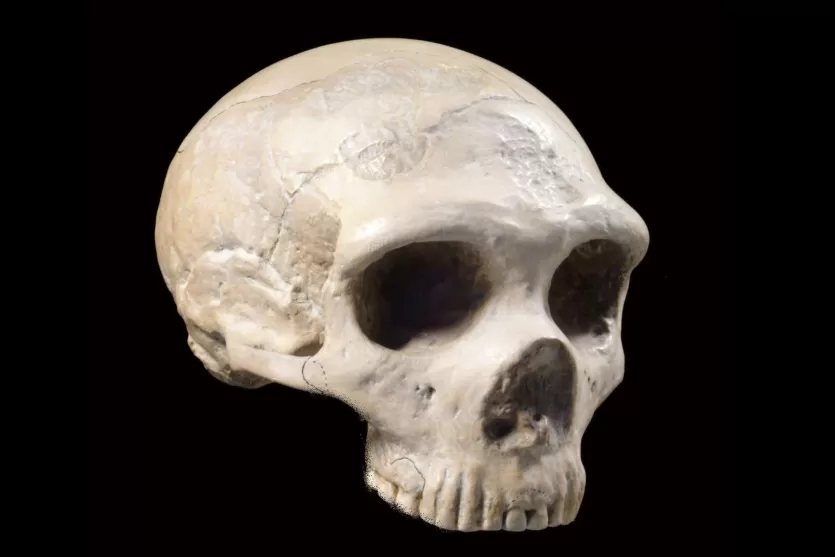

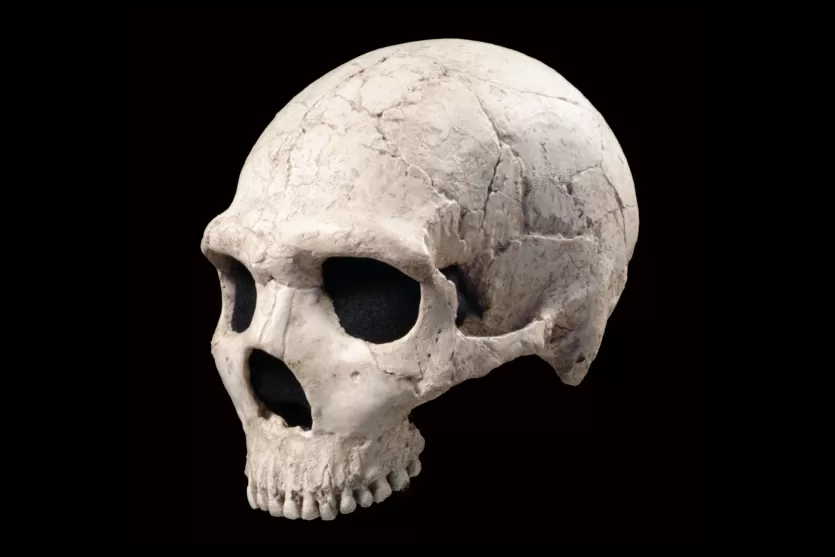

The Neanderthal skull is immediately recognizable: a long, low cranial vault with a prominent occipital bun at the back, a projecting midface with large nasal apertures, double-arched brow ridges (supraorbital tori), and a retromolar space behind the third molar that is absent in modern humans.1 The large nasal cavity has been interpreted as an adaptation for warming and humidifying cold, dry air before it reached the lungs, though it may also reflect a generally prognathic facial architecture inherited from earlier Homo species.7

Perhaps the most striking feature of Neanderthal anatomy is brain size. Neanderthal endocranial volumes range from approximately 1,172 to 1,740 cubic centimeters, with a mean of roughly 1,410 cc — equal to or slightly exceeding the modern human average of about 1,350 cc.8 The largest Neanderthal cranium on record, Amud 1 from Israel, had an endocranial volume of 1,736–1,740 cc, placing it among the largest ever measured for any human.9 However, when brain size is scaled to body mass, Neanderthals have a somewhat lower encephalization quotient than Homo sapiens, and virtual endocasts suggest subtle differences in brain organization, with relatively smaller parietal and cerebellar regions in Neanderthals.10

Cranial capacity of key Neanderthal specimens compared to modern human average8, 9, 11

Their postcranial skeleton was extraordinarily robust. Neanderthal limb bones have thick cortical walls and pronounced muscle attachment sites, indicating habitual high levels of mechanical loading. Biomechanical analyses suggest Neanderthals engaged in close-range hunting of large prey, a strategy that placed enormous physical demands on the upper body and that is reflected in high rates of traumatic injury comparable to those of modern rodeo riders.12

Behavior and cognition

The behavioral repertoire of Neanderthals has been radically reassessed in recent decades. Once assumed to be cognitively inferior to Homo sapiens, Neanderthals are now known to have engaged in a range of behaviors previously thought unique to our species, including deliberate burial, compassionate care of the injured, use of pigments, feather collection, and possibly the creation of cave art.5, 13

The evidence for intentional Neanderthal burial is extensive. The most thoroughly documented case is La Chapelle-aux-Saints 1, an elderly male whose nearly complete skeleton was found in a pit dug into the bedrock floor of a small cave in southwestern France. Excavated by the brothers Amédée and Jean Bouyssonie in 1908, the skeleton's excellent preservation and the deliberate nature of the pit were debated for decades, but a re-excavation of the site in 2011–2012 confirmed that the depression was intentionally dug and that the body had been rapidly covered, constituting a purposeful burial.14 At La Ferrassie, a rock shelter in the Dordogne, at least seven Neanderthal individuals were buried, including adults and children, in what appears to be a group cemetery — the strongest evidence for repeated funerary behavior in any archaic human species.15

Evidence for compassionate care of the injured is equally compelling. Shanidar 1, nicknamed "Nandy," was a male from Shanidar Cave in Iraqi Kurdistan who had survived a crushing blow to the left orbit that likely blinded him in one eye, a withered and amputated right arm, a healed fracture of the right foot, and degenerative joint disease of the right knee and ankle. Despite these crippling disabilities, skeletal indicators show that he survived for years or even decades after his injuries, an impossibility without sustained assistance from other members of his group.12 La Chapelle-aux-Saints 1 presents a similar picture: the individual had lost nearly all his teeth long before death and suffered from severe osteoarthritis of the spine, hip, and foot, yet lived to an advanced age for a Neanderthal, implying that others processed his food and helped him survive.3, 14

Perhaps the most dramatic recent discovery concerns Neanderthal art. In 2018, uranium-thorium dating of carbonate crusts overlying cave paintings in three Spanish caves — La Pasiega, Maltravieso, and Ardales — yielded minimum ages of 65,000 years, some 20,000 years before the earliest known arrival of Homo sapiens in Europe.13 The paintings include red hand stencils, geometric shapes, and linear motifs. If the dating is correct, these represent the oldest known cave art anywhere in the world and demonstrate that Neanderthals possessed the capacity for symbolic thought. The findings remain debated, with some researchers questioning the reliability of the dating technique on thin carbonate layers, but subsequent studies have broadly supported the original results.13, 16

Additional evidence for symbolic behavior includes the collection of raptor talons and feathers at multiple sites, interpreted as ornamental use, and the application of red and black pigments (ochre and manganese dioxide) to the body or to objects, which has been documented at sites from France to the Caucasus.5, 16 At Krapina in Croatia, a set of eight white-tailed eagle talons bearing cut marks and polishing consistent with mounting in a necklace or bracelet has been dated to approximately 130,000 years ago, well before any contact with Homo sapiens in Europe.17

The Levantine corridor

The Levant — the strip of Mediterranean coastland running through modern Israel, Lebanon, and Syria — is the only region where Neanderthals and Homo sapiens are known to have coexisted over a prolonged period. The fossil record from caves on Mount Carmel and in the Galilee documents an extraordinary overlap spanning tens of thousands of years, though whether the two species were simultaneously present or alternated in the region remains debated.18

Tabun Cave on Mount Carmel has yielded one of the oldest known Levantine Neanderthals. Tabun C1, a nearly complete female skeleton excavated by Dorothy Garrod between 1929 and 1934 and described by Theodore McCown and Arthur Keith in 1939, has been dated to approximately 170,000 years ago by electron spin resonance and uranium-series methods, though some estimates place it considerably younger.19, 18 Less than 100 meters away, the Skhul cave yielded early Homo sapiens fossils dated to roughly 100,000–130,000 years ago, demonstrating that both species inhabited the same narrow landscape, though not necessarily at the same time.18

Kebara Cave, also on Mount Carmel, produced one of the most important Neanderthal finds from the region. Kebara 2, nicknamed "Moshe," is dated to approximately 60,000 years ago and preserves the most complete Neanderthal postcranial skeleton ever found, including a pelvis, vertebral column, ribs, and — critically — an intact hyoid bone.20 The hyoid is a small horseshoe-shaped bone in the throat that anchors the muscles used in speech. The Kebara 2 hyoid is virtually identical in size, shape, and internal microstructure to that of modern humans, leading researchers to conclude that Neanderthals possessed at least the anatomical prerequisites for speech, though the question of whether they had language remains unresolved.21

Amud Cave in the Upper Galilee produced the Neanderthal with the largest known cranial capacity of any human, living or fossil. Amud 1, excavated by Hisashi Suzuki in 1961 and dated to approximately 60,000 years ago, had an endocranial volume of 1,736–1,740 cc. At 178 centimeters tall, Amud 1 was also unusually tall for a Neanderthal, perhaps reflecting less extreme cold adaptation in the milder Levantine climate.9

Key specimens

Notable Neanderthal specimens covered in this article2, 9, 12, 19

| Specimen | Age (ka) | Location | Key significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tabun C1 | ~170 | Mount Carmel, Israel | One of the oldest Levantine Neanderthals |

| Gibraltar 1 | ~90 | Gibraltar | First adult Neanderthal skull found (1848) |

| Shanidar 4 | ~73 | Iraqi Kurdistan | Controversial "flower burial" |

| Kebara 2 | ~60 | Mount Carmel, Israel | Most complete postcranium; first hyoid bone |

| La Chapelle 1 | ~60 | France | First near-complete skeleton; evidence of elder care |

| Amud 1 | ~60 | Galilee, Israel | Largest cranial capacity of any human (1,740 cc) |

| La Ferrassie 1 | ~47 | Dordogne, France | Second-largest endocranial volume (1,641 cc); intentional burial |

| Feldhofer 1 | ~40 | Neander Valley, Germany | Holotype; first recognized fossil human |

| Shanidar 1 | ~40 | Iraqi Kurdistan | Multiple healed injuries; evidence of compassionate care |

Interbreeding with Homo sapiens

The most revolutionary development in Neanderthal research came in 2010, when a team led by Svante Pääbo at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology published a draft Neanderthal genome assembled from three female individuals from Vindija Cave in Croatia. Comparison with five modern human genomes revealed that non-African populations carried significantly more Neanderthal-derived alleles than sub-Saharan African populations, a pattern best explained by gene flow from Neanderthals into the ancestors of all non-Africans after their departure from the continent.4 The initial estimate of 1–4% Neanderthal ancestry in non-African genomes has been refined by subsequent studies to approximately 1.5–2.1% in most Eurasian populations, with East Asians carrying slightly more Neanderthal DNA than Europeans.22, 23

The timing of interbreeding has been estimated through analysis of linkage disequilibrium — the pattern of Neanderthal DNA segments that shorten with each generation of recombination. The primary admixture event appears to have occurred between approximately 50,000 and 60,000 years ago, most likely in the Near East as expanding Homo sapiens populations first encountered Neanderthals outside Africa.22 However, more recent work has identified evidence of multiple episodes of gene flow, some as recent as 40,000 years ago, and some involving gene flow from Homo sapiens into Neanderthal populations as well.24

Neanderthal DNA in modern humans is not randomly distributed across the genome. Natural selection appears to have removed Neanderthal alleles from regions near genes, particularly genes expressed in the brain and testes, suggesting that many introgressed variants were mildly harmful in the Homo sapiens genetic background.23 Nonetheless, some Neanderthal alleles appear to have been positively selected. Variants influencing immune function, particularly in the toll-like receptor and human leukocyte antigen gene families, reached high frequencies in modern populations, likely because they conferred resistance to local pathogens that Neanderthals had adapted to over hundreds of millennia in Eurasia.25 Other Neanderthal-derived variants have been associated with skin and hair pigmentation, fat metabolism, and even susceptibility to certain diseases including type 2 diabetes and depression, though the effect sizes of individual variants are typically very small.25

Extinction

Neanderthals disappeared from the fossil record between approximately 40,000 and 30,000 years ago, with the last known populations persisting in southern Iberia and possibly in pockets of the Caucasus.26 Their extinction coincided with the spread of anatomically modern humans into Europe during the Upper Paleolithic, and the question of whether Homo sapiens caused, accelerated, or merely witnessed the Neanderthal decline remains one of the most debated topics in paleoanthropology.1

Several hypotheses have been proposed. The competition model argues that Homo sapiens possessed slight but decisive advantages in technology, social organization, or subsistence strategies that allowed them to outcompete Neanderthals for the same resources. Modeling studies have shown that even a very small competitive advantage — as little as 2% greater efficiency in resource exploitation — would be sufficient to drive Neanderthal extinction over a few thousand years when compounded across a landscape shared by two expanding populations.27 An ecocultural niche model published in 2016 found that the southward retreat of Neanderthal populations during a warm interstadial period could not be explained by climate alone and was better accounted for by geographic competition with expanding Homo sapiens populations.28

Climate change almost certainly played a contributing role. The period of Neanderthal decline coincided with Heinrich Event 4, a massive discharge of icebergs into the North Atlantic that caused abrupt cooling and vegetation shifts across Europe.26 Neanderthal populations were already small and fragmented, as ancient DNA analyses indicate very low genetic diversity in their final millennia, making them vulnerable to stochastic extinction from environmental shocks even without direct competition from Homo sapiens.4

A third possibility is genetic absorption: rather than dying out entirely, Neanderthals were gradually assimilated into the larger and more rapidly growing Homo sapiens population through interbreeding. Under this model, the Neanderthal phenotype disappeared not because every Neanderthal died without reproducing but because their genes were diluted beyond recognition in an expanding modern human gene pool.29 The discovery of 1–4% Neanderthal DNA in all non-Africans provides direct support for at least a partial genetic absorption, even if complete assimilation is unlikely given the archaeological evidence for population replacement at most European sites.4

From brute to human

The rehabilitation of the Neanderthal image over the past half-century represents one of the most dramatic shifts in the history of paleoanthropology. Marcellin Boule's 1911–1913 monograph on La Chapelle-aux-Saints 1 depicted Neanderthals with a stooped posture, divergent big toes, and a forward-thrust head, more ape than human.3 This reconstruction influenced both scientific and popular perceptions for decades and was reinforced by mid-twentieth-century textbooks and museum exhibits that portrayed Neanderthals as hairy, slouching primitives incapable of fully upright posture.

The turning point came in the 1950s and 1960s, when the anatomists William Straus and A. J. E. Cave re-examined the La Chapelle skeleton and showed that Boule had failed to account for the individual's severe osteoarthritis. A healthy Neanderthal, they concluded, would have walked as upright as any modern human and, "if he could be reincarnated and placed in a New York subway — provided that he were bathed, shaved, and dressed in modern clothing — it is doubtful whether he would attract any more attention than some of its other denizens."30

Subsequent decades of research have only reinforced this reassessment. The discovery of the Kebara 2 hyoid bone in 1989 suggested the anatomical capacity for speech.21 The identification of the FOXP2 gene — a gene associated with speech and language in modern humans — in Neanderthal DNA provided further evidence that they may have possessed some form of spoken language.31 The accumulating evidence for burial practices, symbolic use of pigments and feathers, care for the injured, and possible cave art has collapsed the behavioral distance between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens to a degree that would have astonished researchers a generation ago.5, 13, 17

Evolutionary significance

Neanderthals are central to the story of human evolution for several reasons. First, they are our closest known evolutionary relatives. Molecular clock estimates based on mitochondrial and nuclear DNA place the divergence of the Neanderthal and Homo sapiens lineages at approximately 550,000–765,000 years ago, with the two species likely descending from a common ancestor in Africa, probably Homo heidelbergensis or a closely related population.4, 1

Second, the Neanderthal genome demonstrates that speciation in the genus Homo was not always clean or complete. The confirmed interbreeding between Neanderthals and Homo sapiens shows that these two lineages, despite hundreds of thousands of years of separate evolution in different continents, remained biologically compatible when they met. This has profound implications for how we define species boundaries in the human lineage and challenges the traditional view of human evolution as a simple branching tree.4, 24

Third, the Neanderthal record provides a powerful counterexample to the claim that humans are fundamentally different from all other animals. If Neanderthals buried their dead, cared for the disabled, decorated their bodies, and possibly painted cave walls, then the cognitive and behavioral traits we consider quintessentially human did not arise uniquely in our lineage but evolved convergently or were inherited from a shared ancestor. The Neanderthal story forces us to reconsider not just who our relatives were, but what it means to be human at all.5, 13