In September 2003, an Indonesian-Australian excavation team working in Liang Bua, a limestone cave on the island of Flores, uncovered a nearly complete skeleton that would reshape the study of human evolution. The individual, catalogued as LB1, was an adult female who stood approximately 1.06 meters tall and possessed a cranial capacity of roughly 380 cubic centimeters, smaller than the average chimpanzee brain.1 When Peter Brown, Thomas Sutikna, Michael Morwood, and colleagues published the discovery in Nature in October 2004, they assigned it to a new species: Homo floresiensis.1 The media immediately dubbed the species "the Hobbit," and the discovery ignited one of the most intense debates in modern paleoanthropology, touching on questions of island evolution, brain size, tool use, and what it means to be human.2

Fifteen years later, a second shock arrived from the Philippines. In 2019, Florent Détroit and colleagues described Homo luzonensis from Callao Cave on the island of Luzon, based on teeth and small bones that exhibited an unexpected combination of features seen in both Australopithecus and later Homo species.3 Together, these two island species have fundamentally altered the understanding of hominin diversity in Southeast Asia and demonstrated that isolated island environments could drive remarkable evolutionary trajectories in the human lineage.

Discovery of Homo floresiensis

The Liang Bua excavations had been underway since 2001 under the direction of the late Michael Morwood of the University of New England and R. P. Soejono of the Indonesian Centre for Archaeology.2 The team was searching for evidence of the earliest modern human migration through the Indonesian archipelago when they encountered the LB1 skeleton in Sector VII of the cave, buried in deposits dated to approximately 80,000 years ago.1 The skeleton was approximately 40% complete, preserving the cranium, mandible, pelvis, femora, tibiae, and portions of the hands and feet.1

The announcement generated worldwide media attention and immediate controversy. Here was an adult hominin with a body the size of a three-year-old modern human child and a brain smaller than that of any known Homo species, yet the associated archaeological deposits contained sophisticated stone tools and evidence of fire use.1, 4 Subsequent excavations recovered bones and teeth representing as many as twelve additional individuals, confirming that LB1 was not a unique anomaly but representative of a population that inhabited the cave over a span of tens of thousands of years.5

Initial dating suggested that H. floresiensis might have survived until as recently as 12,000 years ago, which would have made it contemporary with the spread of agriculture.1 However, a comprehensive re-analysis of the Liang Bua stratigraphy published by Thomas Sutikna and colleagues in 2016 significantly revised this timeline. The skeletal remains of H. floresiensis now date to between approximately 100,000 and 60,000 years ago, while the associated stone tools extend from about 190,000 to 50,000 years ago.6 This revision means that the species disappeared around the time modern humans were first arriving in the region, raising questions about whether the two species ever met and whether competition played a role in the extinction of H. floresiensis.6

Anatomy and morphology

The physical characteristics of H. floresiensis are extraordinary by any measure within the genus Homo. LB1's estimated stature of 1.06 meters places it well below the range of any known human population, living or extinct.1 The cranial capacity of approximately 380 cc is comparable to that of Australopithecus species that lived three million years earlier and is roughly one-third the size of the average modern human brain.1, 7

Despite the small brain, the endocast (internal cast of the braincase) reveals a brain that was not simply a scaled-down version of an earlier hominin brain. Dean Falk and colleagues showed that the LB1 endocast possesses derived features in the frontal and temporal lobes, including an expanded Brodmann's area 10, a region associated with higher cognitive functions such as planning and initiative-taking in modern humans.7 The overall morphology of the endocast more closely resembles that of Homo erectus than that of microcephalic modern humans, a finding that would prove critical in the debate over the species' validity.7

The postcranial skeleton displays its own suite of unusual features. The arms are relatively long compared to the legs, a proportion more reminiscent of early Homo or Australopithecus than of modern humans.1 The feet are exceptionally long relative to the lower legs, with a divergent big toe that suggests a gait somewhat different from the fully modern human stride.8 The wrist bones lack certain derived features found in modern humans and Neanderthals, instead retaining a more primitive morphology similar to that seen in African apes and early hominins.9 The shoulder joint is configured in a way that would have positioned the arms slightly more forward than in modern humans, a feature shared with H. erectus.1

Cranial capacity comparison across Homo species1, 10

The microcephaly debate

Almost immediately after the 2004 publication, a group of researchers led by Maciej Henneberg, Teuku Jacob, and Robert Martin challenged the new species designation. They proposed that LB1 was not a representative of a new species at all, but rather a pathological modern human suffering from microcephaly, a developmental condition that produces an abnormally small head.11 The stakes were high: if LB1 was merely a diseased Homo sapiens, the entire edifice of a new island-dwelling species would collapse.

The microcephaly hypothesis generated a series of studies and counter-studies that consumed much of the paleoanthropological literature for nearly a decade. Martin and colleagues argued in 2006 that LB1's brain volume fell within the range of known microcephalic humans and that the brain-to-body scaling relationship was consistent with pathology rather than a new species.11 Other diagnoses were subsequently proposed, including Laron syndrome (a growth hormone insensitivity disorder), Down syndrome, and cretinism caused by iodine deficiency.12

However, multiple independent lines of evidence have since decisively refuted the pathological interpretation. Falk and colleagues demonstrated in 2005 and 2007 that the shape of LB1's endocast differs fundamentally from those of microcephalic humans. Using geometric morphometric analysis, they showed that classification functions consistently sort LB1 with normal humans and H. erectus rather than with microcephalics.7, 13 Karen Baab and Kieran McNulty confirmed this finding using three-dimensional cranial landmark analysis, showing that LB1's skull shape is not that of a pathological modern human.14

Perhaps the most decisive evidence against the pathological hypothesis came from the discovery of additional individuals. If LB1 were a lone pathological specimen, one would not expect to find multiple individuals of similar stature at the same site. Yet the Liang Bua excavations recovered remains of at least nine to twelve additional individuals, including a second mandible (LB6) and a tibia (LB8) that are comparably small.5 Furthermore, craniometric analysis published by Baab, McNulty, and Harvati in 2013 confirmed that the Liang Bua sample represents a population of small-bodied individuals, not a collection of pathological outliers.14

The wrist morphology provided yet another independent line of refutation. Matthew Tocheri and colleagues showed in 2007 that the carpal (wrist) bones of LB1 retain a primitive, trapezoid-shaped morphology that is fundamentally different from the derived configuration found in all modern humans, whether healthy or pathological. No known developmental pathology transforms modern human wrist bones into the ancestral shape.9 Similarly, the primitive foot morphology documented by William Jungers and colleagues, including the long feet and curved toe bones, cannot be explained by any known pathological condition in modern humans.8

By the mid-2010s, the microcephaly hypothesis had been largely abandoned by the paleoanthropological community. The convergence of evidence from endocast morphology, cranial shape analysis, postcranial anatomy, wrist and foot structure, and the presence of multiple individuals of similar size and proportions left little room for a pathological interpretation.14, 15

Insular dwarfism and the island rule

The most widely accepted explanation for the diminutive size of H. floresiensis is insular dwarfism, an evolutionary phenomenon in which large-bodied animals isolated on islands evolve progressively smaller body sizes over generations. This pattern, sometimes called the "island rule," has been documented in a wide range of mammals including elephants, hippopotami, deer, and primates.16 The mechanism is straightforward: islands typically offer limited resources, reduced predation pressure, and smaller home ranges, all of which favor smaller body size.16

Flores itself provides a textbook example of island evolution. The island was home to Stegodon, a proboscidean (elephant relative) that underwent dramatic dwarfing, with some Flores populations reaching body masses only about 15% that of their mainland ancestors.17 Giant rats, oversized Komodo dragons, and large storks also inhabited the island, illustrating the broader pattern in which large species shrink and small species grow on islands.2 In this ecological context, the dwarfing of a hominin lineage, while unprecedented, is not biologically implausible.

The question of which ancestral species gave rise to H. floresiensis has been debated. The original describers suggested that it descended from a population of Homo erectus that reached Flores and subsequently underwent dwarfing.1 This hypothesis received strong support in 2016 when Gerrit van den Bergh and colleagues reported H. floresiensis-like fossils from Mata Menge, a site approximately 74 kilometers from Liang Bua, dated to approximately 700,000 years ago.18 The Mata Menge specimens, comprising a partial mandible and six teeth from at least three individuals, are morphologically similar to the Liang Bua material but even smaller in some dimensions, suggesting that the dwarfing process was already well advanced by the early Middle Pleistocene.18

An alternative hypothesis, championed by Debbie Argue and colleagues, proposes that H. floresiensis descended not from H. erectus but from an earlier, more primitive Homo species, perhaps one closely related to H. habilis, that dispersed out of Africa before H. erectus.19 This hypothesis draws on the many primitive features of the H. floresiensis skeleton, including the long arms, primitive wrist bones, and small brain, which would require remarkably extensive evolutionary reversal if the ancestor were H. erectus.19 The debate remains unresolved, though the Mata Menge fossils, which are described as more derived than Australopithecus and H. habilis, tend to support the H. erectus ancestry model.18

Stone tools and the question of cognition

One of the most provocative aspects of H. floresiensis is the association between a very small brain and relatively sophisticated behavior. The stone tools found at Liang Bua are broadly comparable to Oldowan-type assemblages, involving simple flake production from cobble cores, but they also include evidence of more complex reduction sequences.4 The tools span a period from approximately 190,000 to 50,000 years ago, and their consistent presence throughout the stratigraphic sequence indicates sustained technological tradition rather than occasional or accidental tool use.6

Stone tools on Flores actually predate H. floresiensis by a considerable margin. In 1998, Morwood and colleagues reported stone artifacts from the Soa Basin dated to approximately 840,000 years ago, well before the earliest known H. floresiensis fossils.20 These artifacts were associated with the remains of butchered Stegodon, suggesting that the hominin colonizers of Flores were already capable of organized hunting or scavenging upon arrival.20 Adam Brumm and colleagues subsequently documented additional artifacts from Mata Menge dated to approximately one million years ago, extending the record of hominin presence on the island even further back in time.21

The existence of stone tool manufacture by a hominin with a brain volume of 380 cc challenges long-held assumptions about the relationship between brain size and cognitive ability. While the tools of H. floresiensis are not as elaborate as those made by contemporary H. sapiens, they nonetheless represent deliberate planning, raw material selection, and the transmission of learned technique across generations.4 Evidence from the faunal assemblages at Liang Bua also suggests cooperative hunting of juvenile Stegodon, which would require coordination and communication among group members.2 These findings suggest that absolute brain size is a poor proxy for behavioral complexity and that internal brain organization, neural density, and connectivity may matter more than sheer volume.7

The discovery of Homo luzonensis

The story of Homo luzonensis began in 2007, when zooarchaeologist Philip Piper, sorting through animal bones from excavations led by Armand Salvador Mijares in Callao Cave on the island of Luzon in the Philippines, identified a single hominin foot bone, a third metatarsal.22 Uranium-series dating placed this bone at a minimum age of 67,000 years, making it the oldest direct evidence of a human presence in the Philippines at that time.22 Further excavations in 2011 and 2015 recovered additional specimens from the same stratigraphic layer, including seven teeth, two hand phalanges, two foot phalanges, and a femoral shaft fragment, representing at least three individuals.3

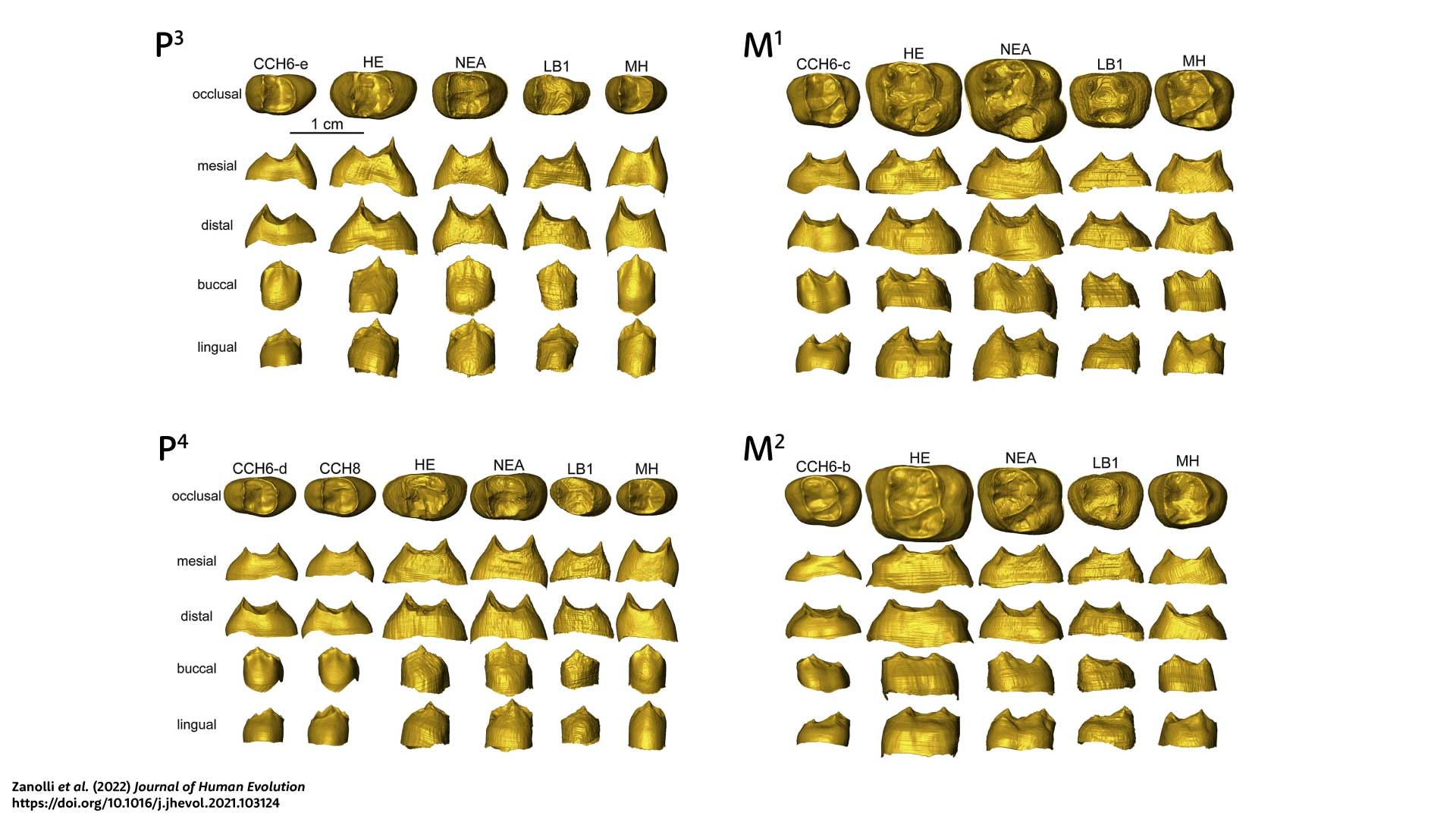

When Détroit and colleagues published the formal description in April 2019, they assigned the specimens to a new species, Homo luzonensis, based on a combination of features that did not fit any existing species definition.3 The teeth are remarkably small, smaller even than those of H. floresiensis in some dimensions, and the premolars exhibit two or three roots, a condition that is extremely rare in Homo sapiens and H. erectus but common in Australopithecus and other early hominins.3 The foot phalanges are strongly curved, resembling those of Australopithecus species more than any member of the genus Homo, suggesting that H. luzonensis may have retained significant arboreal (tree-climbing) capability.3

The mosaic of features is what makes H. luzonensis so challenging to place on the hominin family tree. Some characteristics point to a relationship with H. erectus or H. sapiens, while others appear to have been independently retained from a much more ancient ancestor, or even re-evolved through homoplasy (convergent evolution).3 Direct dating of one of the teeth (CCH6) by uranium-series methods yielded a minimum age of approximately 50,000 years, while the layer containing most of the specimens has been dated to approximately 50,000 to 67,000 years ago.3, 22 However, earlier work by Mijares reported a rhinoceros bone with stone tool cut marks from Kalinga, also on Luzon, dated to approximately 709,000 years ago, suggesting that hominins colonized the island far earlier than the Callao Cave specimens indicate.23

Key specimens

Primary specimens of H. floresiensis and H. luzonensis1, 3

| Specimen | Species | Age (ka) | Site | Key features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LB1 "Flo" | H. floresiensis | ~80 | Liang Bua, Flores | Near-complete skeleton (~40%); ~380 cc cranium; 1.06 m tall |

| LB6 | H. floresiensis | ~60–80 | Liang Bua, Flores | Mandible and postcranial fragments; confirms small population size |

| Mata Menge | H. cf. floresiensis | ~700 | Mata Menge, Flores | Partial mandible and 6 teeth; even smaller than LB1; earliest known |

| CCH6 | H. luzonensis | ~50–67 | Callao Cave, Luzon | Teeth and phalanges; mosaic of australopith-like and Homo features |

| CCH2 (metatarsal) | H. luzonensis | ≥67 | Callao Cave, Luzon | Third metatarsal; first hominin bone found in Philippines |

What island species tell us about human adaptability

The existence of two distinct island hominin species in Southeast Asia has profound implications for understanding human evolutionary diversity and adaptability. Prior to the discovery of H. floresiensis, it was widely assumed that the island rule applied only to non-human animals and that hominins, with their cultural and technological buffers against environmental pressures, were immune to such dramatic evolutionary change.16 The Flores and Luzon discoveries overturned that assumption.

Both species appear to have reached their respective islands by crossing significant water barriers. Flores lies east of Wallace's Line, the biogeographic boundary that separates the Asian and Australasian faunal zones, and has been separated from the mainland by deep-water straits throughout the Pleistocene.20 Luzon, while closer to the Asian mainland, was also never connected by a land bridge during the period in question.23 How pre-modern hominins crossed these water barriers remains one of the great mysteries of paleoanthropology. Intentional seafaring seems unlikely for H. erectus-grade hominins, leading most researchers to invoke accidental rafting on natural vegetation mats carried by currents, perhaps following tsunamis or storms.2

Once established on their respective islands, these hominin populations followed evolutionary trajectories shaped by the unique selective pressures of island environments. In the case of H. floresiensis, the combination of limited resources, the absence of large mammalian predators (though Komodo dragons were present), and competition with other fauna appears to have driven body size reduction over hundreds of thousands of years, as confirmed by the 700,000-year-old Mata Menge fossils.17, 18 For H. luzonensis, the retention or re-evolution of curved toe bones suggests adaptation to a partially arboreal lifestyle, perhaps exploiting the dense tropical forests of Pleistocene Luzon.3

These discoveries also challenge the notion that large brains are a prerequisite for behavioral complexity in the genus Homo. H. floresiensis, with a brain volume comparable to that of Australopithecus afarensis, manufactured stone tools, hunted cooperatively, and persisted for hundreds of thousands of years alongside some of the most extreme fauna in the Indonesian archipelago.1, 4, 7 This evidence suggests that the relationship between brain size and cognitive capacity is far more complex than a simple linear correlation, and that neural reorganization and increased neuronal density may compensate for reduced absolute volume.7

Implications for human evolution

The broader significance of H. floresiensis and H. luzonensis extends well beyond island biology. Their existence demonstrates that as recently as 50,000 years ago, modern humans shared the planet with multiple other hominin species, including Neanderthals in Europe and western Asia, Denisovans in eastern Asia and Oceania, and at least two diminutive island species in Southeast Asia.6, 3 This picture of a multispecies human world in the late Pleistocene is radically different from the view that prevailed as recently as the 1990s, when many paleoanthropologists envisioned a relatively straightforward replacement of archaic humans by modern H. sapiens.15

The island species also raise questions about undiscovered hominin diversity elsewhere in Southeast Asia. The region's tropical environments are notoriously hostile to fossil preservation, and the vast majority of the thousands of islands in the Indonesian and Philippine archipelagoes have never been surveyed for hominin fossils.15 If two separate island species evolved independently on Flores and Luzon, it is entirely plausible that other islands harbored their own endemic hominin populations, now lost to the vagaries of preservation and discovery.2

The timing of the disappearance of both species, roughly coincident with the arrival of modern humans in the region, suggests but does not prove that H. sapiens played a role in their extinction. The revised chronology for Liang Bua places the last appearance of H. floresiensis at approximately 50,000 years ago, and modern humans are known to have reached Australia by at least 65,000 years ago, meaning they must have passed through the Indonesian archipelago before that date.6, 24 Whether the two species competed directly for resources, whether modern humans introduced diseases, or whether environmental changes independent of human activity drove the island species to extinction remains an open and actively investigated question.6

What is certain is that H. floresiensis and H. luzonensis have permanently expanded the known boundaries of human evolutionary diversity. They demonstrate that the genus Homo was capable of producing species that diverged dramatically from the trajectory of increasing brain and body size that characterizes the main line of human evolution. In doing so, they remind us that evolution is not a ladder but a bush, with many branches exploring many ways of being human.15