For most of the history of paleoanthropology, new species of ancient humans were recognized by their bones: a distinctive skull, an unusual jaw, a skeleton that did not match anything previously catalogued. The Denisovans shattered that paradigm. In 2010, a team led by Johannes Krause and Svante Paabo at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology announced that a tiny finger bone fragment from a cave in southern Siberia belonged to a previously unknown lineage of archaic humans, identified not by its shape but by its DNA.1 This discovery inaugurated a new era in which ancient genomics could reveal entire populations invisible to the fossil record. For fifteen years, scientists knew far more about the Denisovan genome than about what Denisovans actually looked like. That changed dramatically in June 2025, when two landmark studies confirmed that the massive Harbin cranium from northeastern China — popularly known as "Dragon Man" — was Denisovan, finally giving a face to the ghost lineage.2, 3

A species born from DNA

Denisova Cave sits in the Altai Mountains of southern Siberia, near the borders of Russia, Kazakhstan, China, and Mongolia. The cave has been the subject of archaeological excavation since the 1970s, yielding stone tools and animal bones from multiple periods of occupation.4 In 2008, Russian archaeologists recovered a small fragment of a distal finger phalanx — the tip of a pinky finger — from the cave's East Gallery, in a layer dated to more than 50,000 years ago. The bone was designated Denisova 3.1

The bone was unremarkable in appearance — too fragmentary to assign to any known species on morphological grounds alone. But when Krause and colleagues extracted mitochondrial DNA from it, they found something extraordinary. The mtDNA sequence diverged from both modern humans and Neanderthals by roughly twice the amount that separates humans from Neanderthals, suggesting that the individual belonged to a lineage that had last shared a common ancestor with the other two groups approximately one million years ago.1 Later that same year, David Reich and colleagues published a nuclear genome from the same specimen, confirming that Denisovans were a sister group to Neanderthals — the two lineages had diverged from each other roughly 390,000 years ago — but were genetically distinct from both Neanderthals and modern humans.5

In 2012, Matthias Meyer and colleagues published a high-coverage genome from the same finger bone, achieving a quality comparable to modern human genome sequences. This extraordinarily complete ancient genome, sequenced to approximately 30-fold coverage, revealed that Denisova 3 was a young female from a population with very low genetic diversity, suggesting a small effective population size.6 The high-quality genome also enabled the first detailed comparisons of Denisovan gene flow into modern human populations, confirming that between 4% and 6% of the genome of present-day Melanesians derives from Denisovan ancestors.5, 6

Denny: the hybrid child

Among the most remarkable individual fossils ever identified is Denisova 11, nicknamed "Denny." In 2012, archaeologists recovered a small bone fragment from Denisova Cave that was initially unidentifiable — one of more than 2,000 visually nondescript bone splinters from the site. Collagen peptide fingerprinting (a technique known as ZooMS) identified it as hominin, and it was sent for DNA analysis.7

In 2018, Viviane Slon and colleagues published the genome of Denisova 11 in Nature, revealing that the individual was a first-generation hybrid: her mother was a Neanderthal and her father was a Denisovan.7 The bone's cortical thickness indicated that Denny had been at least 13 years old at death, and radiocarbon dating placed her at approximately 90,000 years ago.7 The genome showed that roughly 38.6% of her DNA fragments matched the Neanderthal reference genome while 42.3% matched the Denisovan reference, consistent with a roughly equal genetic contribution from each parent. The remaining fragments were either shared between the lineages or too degraded to assign confidently.7

Further analysis of Denny's genome revealed additional layers of complexity. Her Denisovan father carried traces of Neanderthal ancestry in his own genome, indicating that interbreeding between the two groups had occurred on at least one previous occasion.7 Her Neanderthal mother, meanwhile, was genetically more closely related to Neanderthals who lived later in western Europe (specifically the Vindija Cave Neanderthals of Croatia) than to an earlier Neanderthal found in Denisova Cave itself, suggesting that Neanderthal populations migrated between eastern and western Eurasia after about 120,000 years ago.7 The discovery of a first-generation hybrid among the tiny number of archaic specimens sequenced to date implied that interbreeding between Neanderthals and Denisovans was not a rare anomaly but a relatively common occurrence when the two populations encountered each other.8

Beyond Siberia: the Xiahe mandible

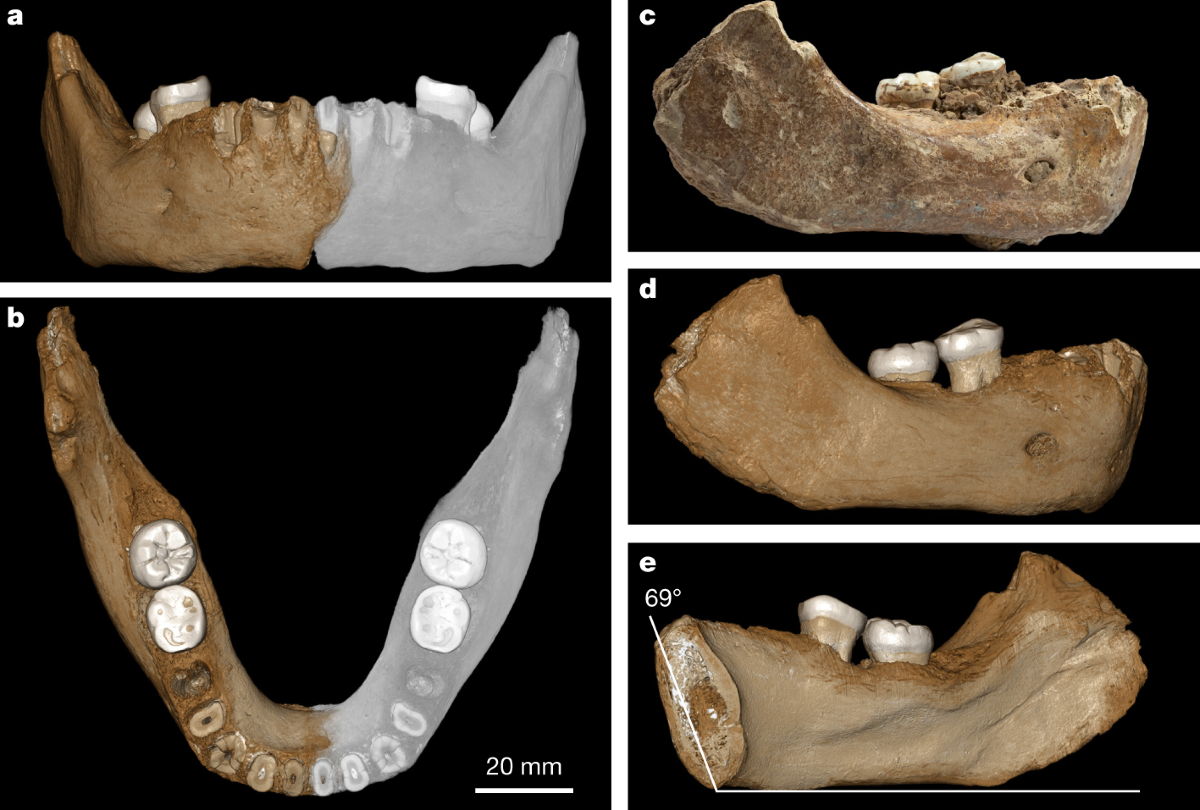

For nearly a decade after the initial discovery, all confirmed Denisovan fossils came from a single cave in Siberia, raising the question of whether Denisovans were merely a local population rather than a widespread lineage. That changed in 2019, when Fahu Chen and colleagues reported on a mandible that had been found in 1980 by a Buddhist monk in Baishiya Karst Cave, located on the Tibetan Plateau at an elevation of 3,280 meters in Xiahe County, Gansu Province, China.9

The mandible preserved two large molars and a robust jawbone, but attempts to extract DNA failed. Instead, the team turned to ancient protein analysis (paleoproteomics), recovering collagen from the dentine of one molar. The protein sequence placed the Xiahe individual closer to Denisovans than to any other known hominin, making it the first Denisovan identified through proteomics and the first confirmed Denisovan fossil outside of Denisova Cave.9 Uranium-series dating of a heavy carbonate crust adhering to the mandible yielded a minimum age of 160,000 years, making it the oldest known Denisovan specimen at the time of publication.9

The discovery carried profound implications. The Tibetan Plateau is one of the most challenging environments on Earth for human habitation, with atmospheric oxygen levels roughly 40% lower than at sea level. The presence of Denisovans at such extreme altitude 160,000 years ago demonstrated that they had successfully adapted to hypoxic conditions long before modern Homo sapiens arrived in the region.9, 10 Subsequent work at Baishiya Karst Cave recovered Denisovan mitochondrial DNA from sediment layers dated to approximately 100,000 and 60,000 years ago, confirming prolonged occupation of the site.11 In 2024, a Denisovan rib identified through proteomics extended their confirmed presence at Baishiya to between 48,000 and 32,000 years ago, indicating that Denisovans may have persisted on the Tibetan Plateau well into the Late Pleistocene.12

The Harbin cranium: a face for the Denisovans

The Harbin cranium has one of the most unusual provenance stories in paleoanthropology. According to the account provided by the family who donated it, the skull was found in 1933 by a laborer working on a bridge over the Songhua River near the city of Harbin in northeastern China, during the Japanese occupation of Manchuria. Rather than hand it over to the Japanese authorities, the worker reportedly hid the skull in an abandoned well, where it remained for more than eight decades. In 2018, shortly before his death, the man told his family about the fossil, and they donated it to the Geoscience Museum of Hebei GEO University.13

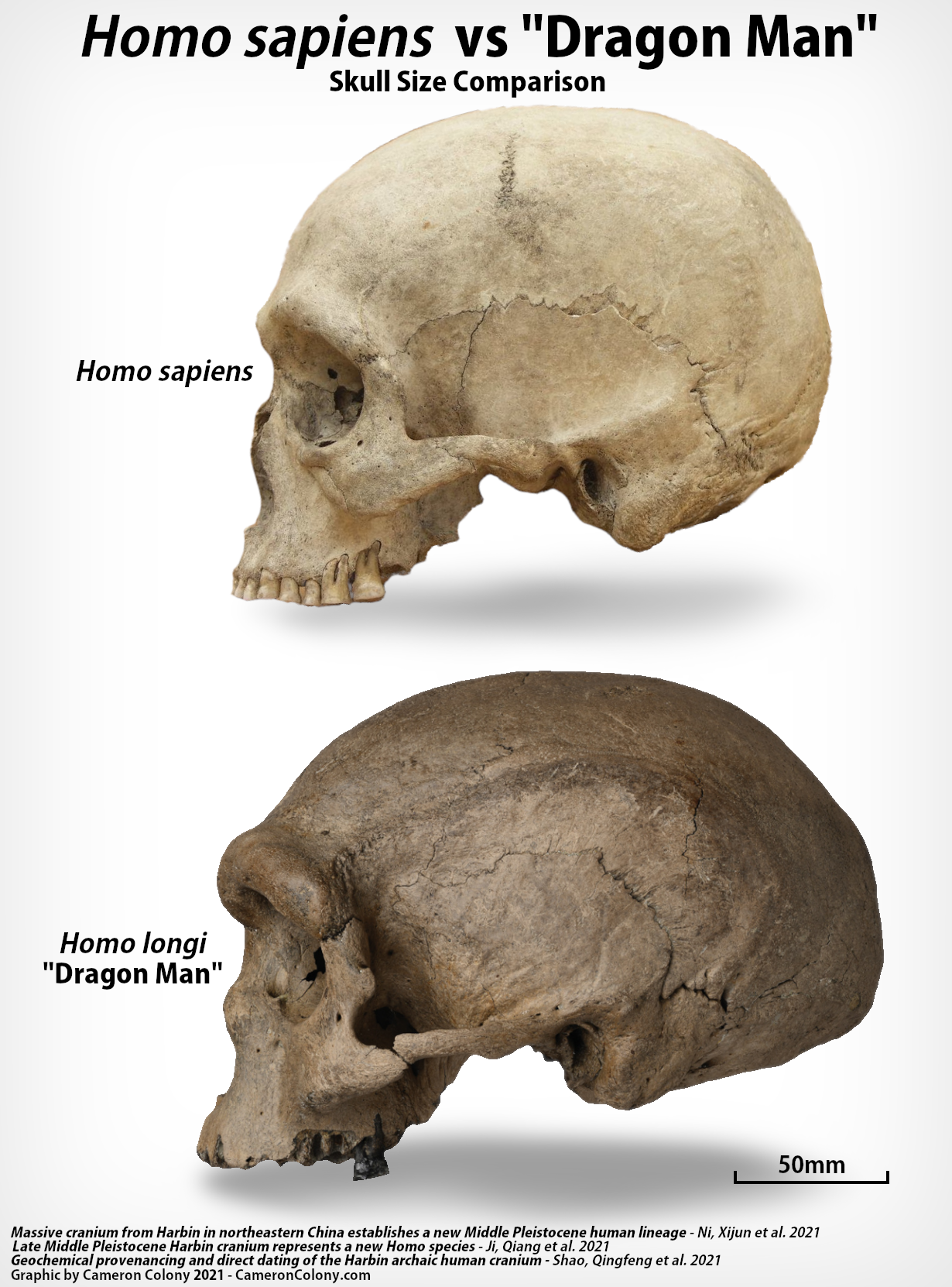

The cranium is massive and nearly complete, preserving the face, braincase, and much of the base of the skull. It combines archaic features — a thick brow ridge, a wide nasal opening, and large, square eye sockets — with a cranial capacity of approximately 1,420 cubic centimeters, within the range of modern humans.13 In 2021, Qiang Ji and colleagues published three papers naming a new species, Homo longi, based on the specimen. Phylogenetic analyses based on morphology placed it closer to Homo sapiens than to Neanderthals, challenging prevailing views of hominin relationships.13, 14 However, many researchers immediately suspected that the cranium might represent a Denisovan, given its geographic location and the known Denisovan presence across East Asia.15

That suspicion was confirmed in June 2025, when two independent studies appeared in Science and Cell. Qiaomei Fu and colleagues at the Chinese Academy of Sciences scraped dental calculus — hardened plaque — from the specimen's teeth and successfully extracted mitochondrial DNA. The mtDNA sequence fell within the Denisovan clade, sharing three variants found exclusively in Denisovan specimens and none in Neanderthals or modern humans.2 The same calculus yielded 95 ancient proteins, three of which matched Denisovan-specific amino acid variants, providing an independent molecular confirmation.3 Together, these results established the Harbin cranium as the first near-complete Denisovan skull, finally revealing what this population looked like: robust, large-brained, and broad-faced, with features distinct from both Neanderthals and modern Homo sapiens.2, 3

Key specimens

Major Denisovan fossil specimens1, 7, 9, 13

| Specimen | Age | Location | Element | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denisova 3 | >50 ka | Denisova Cave, Russia | Distal finger phalanx | First Denisovan identified; complete genome sequenced |

| Denisova 11 ("Denny") | ~90 ka | Denisova Cave, Russia | Long bone fragment | First-generation Neanderthal-Denisovan hybrid |

| Xiahe mandible | ≥160 ka | Baishiya Karst Cave, Tibet | Partial mandible with molars | First Denisovan outside Siberia; protein-identified |

| Harbin cranium | >146 ka | Harbin, China | Near-complete cranium | First Denisovan skull; confirmed by mtDNA in 2025 |

The Denisovan genetic legacy

One of the most consequential findings from the Denisovan genome was the discovery that Denisovans interbred with the ancestors of modern humans, leaving a measurable genetic footprint in populations alive today. The initial analysis by Reich and colleagues in 2010 found that present-day Melanesians carry approximately 4% to 6% Denisovan ancestry, while mainland Asian and Native American populations carry much smaller proportions, typically around 0.2%.5 Subsequent studies using whole-genome sequencing refined these estimates and revealed that the pattern of Denisovan admixture in modern populations is complex, involving at least two or possibly three distinct episodes of interbreeding.16

Denisovan DNA in modern populations5, 16, 17

In 2016, Benjamin Vernot and colleagues analyzed whole-genome sequences from individuals across Island Southeast Asia and Oceania, confirming that Melanesian populations harbor significantly more Denisovan ancestry than any other group. Their analysis estimated admixture proportions between 1.9% and 3.4% using conservative methods, though the actual figure may be higher depending on the reference population and statistical approach used.17 A 2021 study by Maximilian Larena and colleagues found that the Ayta Magbukon of the Philippines carry the highest level of Denisovan ancestry of any population tested, approximately 5%, likely reflecting a distinct admixture event from the one that contributed Denisovan DNA to Melanesians.18

The geographic distribution of Denisovan ancestry presents a puzzle. The only confirmed Denisovan fossils come from Siberia and the Tibetan Plateau, yet the highest levels of Denisovan DNA are found in populations of Island Southeast Asia and Oceania. This pattern suggests that Denisovans were far more widespread across Asia than the sparse fossil record indicates, and that the ancestors of Melanesians and Aboriginal Australians encountered Denisovans somewhere in Southeast Asia as they migrated toward Oceania and Australia.16, 19

Breathing at the roof of the world

Perhaps the most striking example of Denisovan genetic legacy in modern humans involves the EPAS1 gene, which plays a central role in the body's response to low oxygen levels. Tibetans, who have lived at altitudes above 4,000 meters for thousands of years, carry a distinctive variant of EPAS1 that prevents the overproduction of red blood cells at high altitude — a response that in other populations leads to chronic mountain sickness, characterized by dangerously thick blood, hypertension, and heart failure.20

In 2014, Emilia Huerta-Sanchez and colleagues demonstrated that the Tibetan EPAS1 haplotype has an unusual structure that can only be convincingly explained by introgression from Denisovans or a closely related population. The haplotype is found at high frequency in Tibetans (approximately 78%), at low frequency in Han Chinese (less than 1%), and is essentially absent from all other modern human populations — but it matches the Denisovan genome almost perfectly.20 This finding represented one of the clearest known cases of adaptive introgression in human evolution: a gene acquired through interbreeding with an archaic population that conferred a significant survival advantage in a specific environment.20

Subsequent work by Xinjun Zhang and colleagues in 2021 reconstructed the history of the EPAS1 haplotype in more detail. They estimated that the introgression event occurred approximately 48,700 years ago (with a range of 16,000 to 59,500 years ago), and that positive selection for the Denisovan variant began around 9,000 years ago, coinciding with archaeological evidence for permanent settlement of the high Tibetan Plateau.21 The discovery of the Xiahe mandible — a Denisovan living at 3,280 meters at least 160,000 years ago — provided independent evidence that Denisovans had long been adapted to high-altitude environments, making them a plausible source for the altitude-adaptation gene that Tibetans carry today.9, 10

Geographic range and persistence

Genetic evidence suggests that Denisovans ranged across an enormous geographic area, from the Altai Mountains of Siberia to the Tibetan Plateau to Southeast Asia. The multiple waves of Denisovan admixture detected in modern populations imply that genetically distinct Denisovan populations occupied different parts of this range, separated by enough time and distance to have diverged significantly from one another.16, 19

At Denisova Cave itself, archaeological and genetic evidence documents a long history of occupation. Denisovan fossils from the cave span at least from about 200,000 to 50,000 years ago, and the site also preserves Neanderthal remains, indicating that the two populations alternated in their use of the cave or even co-occupied it at times.4, 22 At Baishiya Karst Cave on the Tibetan Plateau, the combined evidence from the Xiahe mandible, sediment DNA, and a recently identified rib bone demonstrates Denisovan presence from at least 160,000 years ago to perhaps as recently as 32,000 years ago — a staggering span of more than 100,000 years at a single high-altitude site.9, 11, 12

Whether Denisovans persisted longer in some areas than in others remains an open question. The Baishiya rib, dated to between 48,000 and 32,000 years ago, would make it contemporaneous with the earliest modern humans in the region, raising the possibility that Homo sapiens and Denisovans overlapped on the Tibetan Plateau.12 If Denisovans survived until 32,000 years ago or later, they would have persisted longer than Neanderthals, who disappeared from the European fossil record by approximately 40,000 years ago.23

Evolutionary significance

The Denisovans have transformed the understanding of human evolution in the Late Pleistocene. Before their discovery, the story of the last few hundred thousand years was dominated by two characters: Neanderthals in western Eurasia and Homo sapiens in Africa. The Denisovans revealed that eastern Eurasia was home to its own major lineage of archaic humans, one that was genetically distinct from Neanderthals despite being their closest relatives, and that contributed significantly to the biology of modern populations.5, 6

The confirmation of the Harbin cranium as Denisovan in 2025 resolved one of the longest-standing puzzles in paleoanthropology: the taxonomic identity of the large-brained, robust-faced hominin fossils of Middle and Late Pleistocene East Asia that had never fit comfortably into Homo erectus, Homo heidelbergensis, or any other recognized species.2, 3 Several other Chinese fossils, including the Dali cranium and the Hualongdong skull, share morphological similarities with the Harbin specimen, and ongoing molecular analysis may eventually assign some of these to the Denisovan lineage as well.15

The Denisovan story also underscores the importance of interbreeding in human evolution. Denny — the child of a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father — demonstrates that hybridization between these lineages was not merely a statistical abstraction inferred from genomes, but a biological reality involving real individuals and real encounters.7 The EPAS1 gene in Tibetans shows that genetic material acquired through such encounters could have lasting adaptive consequences, shaping the biology of modern populations thousands of generations later.20 Far from being a dead branch on the human family tree, the Denisovans are a living presence in the genomes of billions of people today.5, 16