The story of how Homo sapiens left Africa and colonized the globe is one of the most thoroughly documented episodes in all of human evolution. It draws on converging lines of evidence from paleoanthropology, archaeology, genetics, and geochronology that together paint a detailed picture of multiple migration waves, encounters with archaic human populations, and the progressive spread of modern behavior across every habitable landmass on Earth. This article, the final installment in an 18-part series on the human fossil record, traces that dispersal from the earliest forays into the Levant more than 200,000 years ago to the colonization of Australia, Europe, and the Americas, completing the picture of human evolution as a continuous, branching, and entirely natural process.1, 2

The out of Africa model

The out of Africa hypothesis, sometimes called the recent African origin model, holds that anatomically modern humans evolved in Africa between roughly 300,000 and 200,000 years ago and subsequently dispersed to replace or absorb archaic human populations across Eurasia.1 This model was first proposed in its modern form by the paleoanthropologist Chris Stringer and colleagues in the 1980s, building on earlier work by geneticists who demonstrated that African populations harbor the greatest genetic diversity of any human group, consistent with a longer evolutionary history on that continent.3 Mitochondrial DNA analyses by Rebecca Cann, Mark Stoneking, and Allan Wilson in 1987 traced all living humans' maternal lineage to an African common ancestor, popularly dubbed "Mitochondrial Eve," who lived roughly 200,000 years ago.4

The competing multiregional hypothesis, which proposed that modern humans evolved simultaneously across Africa, Asia, and Europe from local archaic populations with gene flow connecting them, has been largely abandoned in its strong form.1 However, the discovery that non-African populations carry Neanderthal and Denisovan DNA has confirmed that the out of Africa dispersal was not a simple replacement but involved episodes of interbreeding, producing what researchers now call the "assimilation model" or "leaky replacement."5, 6 The genetic evidence is unambiguous: the vast majority of ancestry in all living humans traces to Africa, with small but significant contributions from archaic Eurasian populations encountered during the dispersal.5

Early dispersals through the Levant

The Levantine corridor, the narrow land bridge connecting Africa to Eurasia through the Sinai Peninsula and the eastern Mediterranean coast, served as the primary gateway for every known early expansion of Homo sapiens out of Africa. The oldest evidence for modern humans outside Africa now comes from the Misliya Cave on the western slopes of Mount Carmel, Israel, where a partial maxilla with attached teeth was dated to approximately 177,000–194,000 years ago using combined uranium-series and electron spin resonance methods.7 The Misliya specimen displays fully modern dental and facial morphology and was associated with Levallois stone tools, demonstrating that anatomically modern humans had reached the Levant by at least the late Middle Pleistocene.7

Even more striking, though more controversial, is the Apidima 1 cranium from Apidima Cave in southern Greece. In 2019, Katerina Harvati and colleagues published a reanalysis of two crania that had been excavated in the 1970s. Using uranium-series dating and 3D virtual reconstruction, they determined that Apidima 1 dates to approximately 210,000 years ago and displays a distinctly modern rounded posterior cranial profile lacking the characteristic Neanderthal "bun" shape, while Apidima 2, dated to around 170,000 years ago, is Neanderthal.8 If this interpretation holds, it suggests that an early wave of modern humans reached southeastern Europe more than 200,000 years ago but was subsequently replaced by Neanderthals, only for a later wave of Homo sapiens to return tens of thousands of years later.8

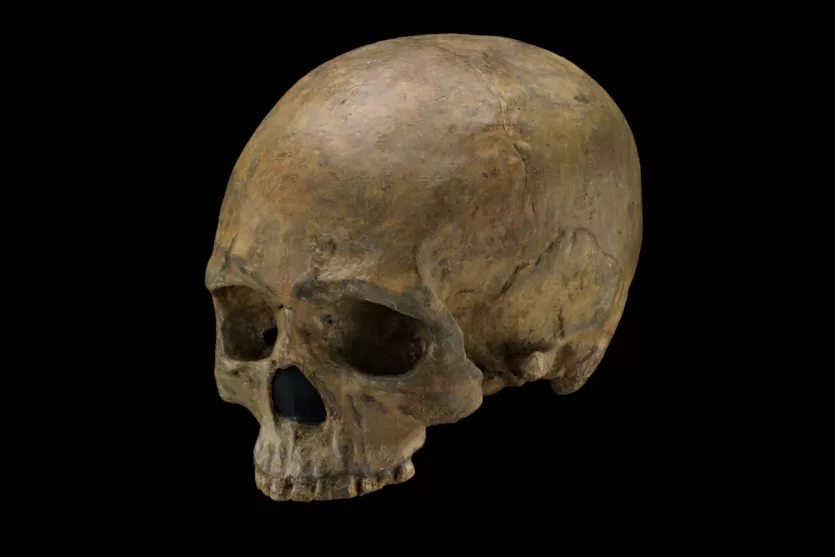

Better-established evidence for early modern human occupation of the Levant comes from the caves of Qafzeh and Skhul, also in Israel. At Qafzeh, thermoluminescence dating of burnt flints from the hominin-bearing layers yielded ages of approximately 90,000–100,000 years before present, revolutionizing understanding of early modern human chronology in southwest Asia.9 The Qafzeh 9 skeleton, one of the best-preserved individuals from the site, was found in what appears to be an intentional burial, with the body placed in a flexed position and a large deer antler laid across the arms, suggesting symbolic or ritual behavior far earlier than the European Upper Paleolithic.9, 10

At nearby Es Skhul on Mount Carmel, electron spin resonance dating of faunal teeth from the burial layers produced ages averaging 81,000–101,000 years ago.11 The Skhul V individual, among the most complete skeletons from the site, was buried in a deliberate pit with what appears to be a boar mandible clasped to the chest, another instance of intentional burial with grave goods predating European parallels by tens of thousands of years.11 Together, the Skhul and Qafzeh populations demonstrate that anatomically modern humans occupied the Levant during a warm interglacial phase roughly 100,000 years ago, but the archaeological record suggests they subsequently disappeared from the region, replaced by Neanderthals during the colder conditions that followed.1, 11

The African cradle

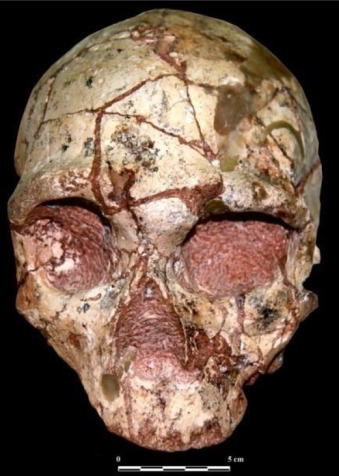

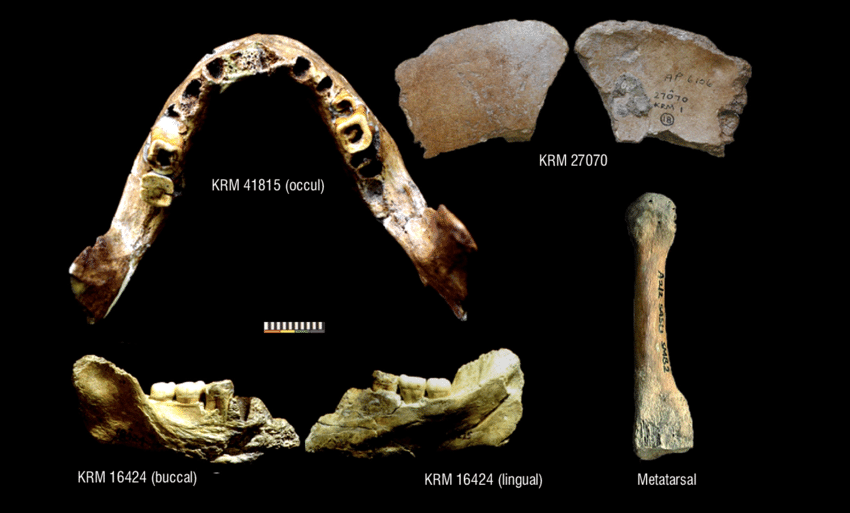

While early waves of modern humans ventured into the Levant, the core population of Homo sapiens continued to evolve in Africa. The Klasies River Mouth caves on the southern coast of South Africa have yielded fragmentary remains of modern humans dating to approximately 90,000–120,000 years ago, including mandible fragments displaying one of the earliest occurrences of a well-developed chin, a distinctively modern anatomical feature.12 The site also preserves evidence of shellfish exploitation and controlled use of fire, suggesting that coastal foraging strategies were part of the behavioral repertoire of early modern Africans.12

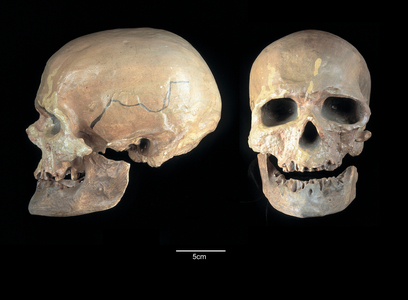

At Border Cave in the Lebombo Mountains of South Africa, a partial cranium designated Border Cave 1 has been dated to approximately 126,000 years ago by electron spin resonance.13 The specimen is striking for its thoroughly modern cranial morphology, including a high, rounded vault and a gracile face. The site has also yielded evidence of complex behavior, including the manufacture of bone tools, the use of ostrich eggshell beads as personal ornaments, and the application of poison to bone points, suggesting that some of the hallmarks of behavioral modernity were present in Africa long before they appear in the European record.13, 14

Perhaps the most compelling evidence for early symbolic thought in Africa comes from Blombos Cave, also on the southern Cape coast of South Africa. In 2002, Christopher Henshilwood and colleagues reported the discovery of two deliberately engraved ochre pieces from levels dated to approximately 77,000 years ago by thermoluminescence.15 The cross-hatched geometric patterns incised into these ochre blocks represent some of the earliest known abstract representations in the human record, predating comparable European evidence by more than 30,000 years. Blombos has also produced perforated shell beads dating to about 75,000 years ago and a 73,000-year-old drawn pattern on a silcrete flake, further establishing southern Africa as a center of early symbolic innovation.15, 16

The major expansion after 70,000 years ago

Although early modern humans reached the Levant by at least 180,000 years ago and possibly southeastern Europe by 210,000 years ago, these early forays appear to have been dead ends. The major, sustained expansion of Homo sapiens out of Africa that led to the permanent colonization of the rest of the world began roughly 60,000–70,000 years ago, as recorded in both the fossil and genetic records.1, 2 Analyses of mitochondrial and Y-chromosome haplogroups in living populations consistently point to a primary dispersal event from eastern Africa during this period, with all non-African populations descending from a relatively small founding group.4, 17

The trigger for this successful expansion remains debated. Some researchers have invoked the Toba supervolcanic eruption approximately 74,000 years ago as a bottleneck event that nearly drove humanity to extinction, though more recent evidence suggests the eruption's effects were less catastrophic than once thought.18 Others point to favorable climatic conditions that periodically "greened" the Sahara and Arabian Peninsula, creating corridors for dispersal from northeastern Africa across the Red Sea or through the Sinai.19 Genetic evidence from whole-genome sequencing of diverse modern populations indicates that the out of Africa bottleneck reduced effective population size to perhaps a few thousand individuals, consistent with a single primary dispersal route, most likely along the southern coast of Arabia and into South Asia.17

The speed of the subsequent dispersal was remarkable. Within roughly 20,000 years of leaving Africa, modern humans had reached Southeast Asia, Australia, and the margins of northern Europe, crossing open water, adapting to extreme cold, and navigating vastly different ecosystems.1 This rapid expansion was likely facilitated by the suite of cognitive and cultural innovations that archaeologists collectively term "behavioral modernity," including sophisticated language, complex social organization, long-distance trade networks, and flexible technological adaptation.2

Colonization of Asia and Australia

The route from Africa to Southeast Asia and Australia represents one of the most remarkable chapters in the out of Africa story. The Tam Pà Ling cave in northern Laos has produced some of the earliest evidence for Homo sapiens in mainland Southeast Asia. In 2023, Sarah Freidline and colleagues reported the discovery of a frontal bone (TPL 6) and tibial fragment (TPL 7) from the deepest sedimentary layers of the cave, with Bayesian modeling of luminescence ages establishing a date of 77,000 ± 9,000 years ago for the tibial fragment, pushing back the earliest evidence for modern humans in the region by more than 30,000 years compared to previous estimates.20 Geometric morphometric analysis of the frontal bone suggests descent from a gracile immigrant population rather than local archaic ancestry, consistent with a dispersal from Africa.20

The colonization of Australia required crossing at least 90 kilometers of open water between the islands of Wallacea (modern Indonesia) and the combined landmass of Sahul (Australia and New Guinea, joined during glacial low sea levels). This maritime crossing, accomplished without the benefit of any known seafaring technology preserved in the archaeological record, represents one of the earliest deliberate ocean voyages by any human population.21 At Madjedbebe, a rock shelter in Australia's Northern Territory, Chris Clarkson and colleagues reported artifacts in primary depositional context dated by optically stimulated luminescence to approximately 65,000 years ago, including grinding stones, ground ochres, and ground-edge hatchet heads, establishing a new minimum age for human arrival on the continent.21

The most iconic early Australian fossil is Lake Mungo 3, known as "Mungo Man," discovered in 1974 near the shores of the now-dry Lake Mungo in New South Wales. In 2003, Jim Bowler and colleagues used a new series of 25 optical ages to establish that the burial occurred at approximately 40,000 ± 2,000 years ago.22 The skeleton was found in an extended burial position covered in red ochre, representing the world's oldest known ritual ochre burial and one of the most culturally significant archaeological finds in Australia. The Lake Mungo 1 cremation from the same site, originally a young woman, represents the earliest known cremation anywhere in the world.22

In East Asia, the Liujiang skeleton from Guangxi Province in southern China has long been one of the most important Homo sapiens fossils from the region. Discovered in 1958, the nearly complete cranium and associated postcranial elements were originally attributed ages as old as 227,000 years by some analyses. However, a comprehensive redating study by Junyi Ge and colleagues in 2024, using uranium-series dating of the fossils themselves and radiocarbon and luminescence dating of the surrounding sediments, established a revised age of approximately 33,000–23,000 years ago.23 This younger age places Liujiang in the context of other Late Pleistocene East Asian Homo sapiens fossils, including those from Tianyuan Cave (approximately 40,000 years ago) and Zhoukoudian Upper Cave (approximately 39,000–36,000 years ago), documenting the geographically widespread presence of modern humans across eastern Asia by the Late Pleistocene.23

Colonization of Europe

Europe was one of the last major regions to be permanently settled by Homo sapiens, in part because Neanderthal populations had occupied the continent for hundreds of thousands of years and were well-adapted to its glacial conditions. The earliest securely dated modern human remains in Europe come from Bacho Kiro Cave in Bulgaria, dated to approximately 45,000 years ago, and from the Ilsenhöhle cave beneath Ranis Castle in Germany.24, 25 At Ranis, Jean-Jacques Hublin and colleagues identified 13 bone fragments as Homo sapiens through proteomic and ancient DNA analysis. These specimens, associated with Lincombian–Ranisian–Jerzmanowician (LRJ) stone tools, were dated to approximately 45,500 years ago, making them the oldest directly dated Homo sapiens remains in northern Europe.25

Stable isotope analysis of the Ranis specimens revealed that these early northern Europeans subsisted on a diet of large terrestrial herbivores, consistent with survival in the cold steppe environment of central Europe during a period when Neanderthal populations still occupied portions of the continent.26 The finding fundamentally changes the understanding of early modern human dispersal into Europe, demonstrating that Homo sapiens had reached high latitudes thousands of years before Neanderthals disappeared from southwestern Europe around 40,000 years ago.25, 26

The most famous early European modern human remains are the Cro-Magnon specimens from the Abî Pataud rock shelter near Les Eyzies in the Dordogne region of France, discovered by railway workers in 1868. The Cro-Magnon 1 individual, an adult male dated to approximately 30,000 years ago, became the first recognized anatomically modern human fossil and was associated with Aurignacian stone tools, perforated shells, and animal teeth used as ornaments.27 The name "Cro-Magnon" subsequently became shorthand for all early modern Europeans, though the term has fallen out of formal scientific use in favor of "anatomically modern human" or simply Homo sapiens.27

Interbreeding with archaic humans

One of the most transformative discoveries of 21st-century paleoanthropology is the genetic evidence that Homo sapiens interbred with both Neanderthals and Denisovans during the out of Africa dispersal. In 2010, Richard Green, Svante Pääbo, and colleagues published the first draft of the Neanderthal genome, assembled from DNA extracted from three individuals from Vindija Cave in Croatia. The genome revealed that Neanderthals shared significantly more genetic variants with modern Eurasian populations than with sub-Saharan Africans, a pattern best explained by gene flow from Neanderthals into the ancestors of all non-African humans.5 Subsequent analyses have refined the Neanderthal contribution to approximately 1–4% of the genome in living non-African populations, with the admixture estimated to have occurred between 50,000 and 60,000 years ago, most likely in the Middle East shortly after the main out of Africa expansion.5, 28

Later that same year, David Reich and colleagues published the genome of a Denisovan individual from Denisova Cave in Siberia, extracted from a single finger bone. The analysis revealed that Denisovans contributed approximately 4–6% of their genetic material to the genomes of present-day Melanesians, Australian Aboriginal peoples, and other Oceanian populations, but left little trace in mainland Asian or European genomes.6 Subsequent work has identified at least two distinct pulses of Denisovan admixture in different Asian and Oceanian populations, suggesting multiple encounters between modern humans and Denisovan groups as Homo sapiens dispersed through Southeast Asia toward Australia.29

This archaic admixture was not merely a genetic footnote. Natural selection has retained some Neanderthal-derived gene variants at high frequency in modern populations because they conferred adaptive advantages. These include variants affecting immune function, particularly genes in the toll-like receptor family and the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) system, as well as variants influencing skin and hair pigmentation, fat metabolism, and cold tolerance.28 Denisovan-derived variants have been linked to adaptation to high altitude in Tibetan populations, where the EPAS1 gene variant that improves oxygen metabolism at low atmospheric pressures was inherited from Denisovan ancestors.30 Far from diminishing the out of Africa model, these findings enrich it, showing that human evolution involved not just migration and replacement but also genetic exchange that helped our species adapt to new environments.5, 6

Archaic DNA in modern human populations5, 6, 29

The behavioral revolution

The global dispersal of Homo sapiens was accompanied by, and likely dependent upon, a suite of behavioral innovations that distinguish modern humans from all earlier hominins. Archaeologists refer to this transformation as the "behavioral revolution" or the emergence of "behavioral modernity," characterized by symbolic expression, technological innovation, and complex social organization.2 The evidence for this revolution comes from dozens of sites across Africa, the Levant, Europe, and Australia, and it accumulates progressively in the archaeological record rather than appearing suddenly at a single moment.15, 16

The intentional burials at Qafzeh (approximately 100,000 years ago) and Skhul (approximately 90,000 years ago) are among the earliest evidence for symbolic behavior by Homo sapiens, predating comparable Neanderthal burials and demonstrating that concepts of death and ritual were part of the modern human cognitive toolkit deep in the Middle Pleistocene.9, 10, 11 The engraved ochre at Blombos Cave (77,000 years ago), the perforated shell beads from the same site (75,000 years ago), and the ochre burial at Lake Mungo (40,000 years ago) trace a continuous thread of symbolic practice across time and space.15, 22

In Europe, the Upper Paleolithic explosion of art and technology is particularly well documented. The Chauvet Cave paintings in southern France, dated to approximately 36,000 years ago, represent some of the most sophisticated figurative art in the Paleolithic record, depicting lions, rhinoceroses, horses, and other animals with remarkable anatomical accuracy and dynamic composition.31 The carved ivory figurines from Hohle Fels Cave in Germany, including a 40,000-year-old Venus figurine and a mammoth ivory flute, attest to the early development of both representational art and music in Europe.32 These cultural achievements were not the result of a biological change in brain capacity, as the brains of the Skhul and Qafzeh people were essentially the same size as those of living humans, but rather reflect the cumulative development of cultural and cognitive complexity over tens of thousands of years.2

Key specimens

Key Homo sapiens fossils documenting the out of Africa dispersal7, 8, 9, 11, 20, 22, 23, 25

| Specimen | Age (ka) | Location | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apidima 1 | ~210 | Greece | Potentially oldest H. sapiens in Europe |

| Misliya maxilla | 177–194 | Israel | Oldest modern human outside Africa |

| Border Cave 1 | ~126 | South Africa | Early complex behavior, modern morphology |

| Qafzeh 9 | ~100 | Israel | Intentional burial with grave goods |

| Skhul V | ~90 | Israel | Intentional burial, key out of Africa evidence |

| Klasies River | ~90 | South Africa | Earliest evidence of modern chin |

| Tam Pà Ling | ~77 | Laos | Earliest H. sapiens in mainland SE Asia |

| Ranis Cave | ~45.5 | Germany | Oldest H. sapiens in northern Europe |

| Lake Mungo 3 | ~40 | Australia | Oldest ritual ochre burial |

| Cro-Magnon 1 | ~30 | France | First recognized anatomically modern human |

| Liujiang | 23–33 | China | Well-preserved Late Pleistocene East Asian |

Geographic spread over time

The scatter plot below illustrates the chronological and geographic pattern of the out of Africa dispersal, with each point representing a key fossil specimen. The horizontal axis represents thousands of years before present, while the vertical axis represents approximate distance from eastern Africa. The pattern reveals both the early, tentative forays into the Levant and the rapid, sustained expansion after approximately 70,000 years ago that carried modern humans to the far corners of the globe.1, 2

Out of Africa dispersal: distance from eastern Africa over time1, 2

Completing the picture

This article concludes an 18-part series tracing human evolution from the very beginning. The series opened with Sahelanthropus tchadensis, a 7-million-year-old ape from Chad that may represent the earliest known hominin, and has traced the branching, overlapping, and sometimes surprising pathway through dozens of species and hundreds of fossil specimens to arrive here: the global dispersal of our own species. Across these articles, several themes emerge that together make the case for human evolution as a natural, well-documented process.1, 2

First, the fossil record is not a chain but a bush. At virtually every point in the last seven million years, multiple hominin species coexisted, each representing a different evolutionary experiment in bipedalism, brain expansion, tool use, or social organization. Homo sapiens is the sole surviving twig on this densely branching tree, but our solitary status is a recent phenomenon; as recently as 50,000 years ago, at least four distinct hominin species shared the planet: Homo sapiens, Neanderthals, Denisovans, and Homo floresiensis.1

Second, each major transition in human evolution is documented by transitional forms. The shift from ape-like ancestors to bipedal hominins is recorded in Ardipithecus and Australopithecus anamensis. The emergence of the genus Homo is documented by Homo habilis and early African Homo erectus. The evolution of large brains and complex technology is traced through Homo heidelbergensis and its descendants. And the origin and dispersal of our own species is recorded in the fossils described in this article and its companion on early African Homo sapiens. At no point does the record require an appeal to supernatural intervention; every step is explicable through the known mechanisms of mutation, natural selection, genetic drift, and gene flow.1, 2

Third, the genetic evidence independently confirms and extends the fossil evidence. Mitochondrial and nuclear DNA analyses trace all living humans to an African origin, document the interbreeding events with archaic populations that accompanied the dispersal, and provide independent dates that are consistent with the fossil chronology.4, 5, 6 The convergence of multiple independent lines of evidence, from anatomy to genetics to archaeology to geochronology, is precisely what one would expect if human evolution actually occurred and is not what one would expect if it were fabricated or illusory.1

The out of Africa dispersal is the final chapter in this story: the moment when a single African primate species, equipped with language, culture, and an unprecedented capacity for innovation, spread across the entire habitable world and, in doing so, became the most ecologically dominant species the planet has ever known. Every step of this journey, from the first tentative footsteps of a bipedal ape in Chad to the ritual ochre burial of Mungo Man on the shores of an Australian lake, is documented in bone, stone, and DNA. The evidence for human evolution is not a matter of faith; it is a matter of record.1, 2