Homo heidelbergensis occupies one of the most consequential positions in the human family tree. Living during the Middle Pleistocene, roughly 700,000 to 200,000 years ago, this species bridges the gap between the earlier Homo erectus and the three lineages that would come to dominate the Late Pleistocene: Neanderthals in Europe, Denisovans in Asia, and anatomically modern humans in Africa.1, 2 Fossils attributed to H. heidelbergensis have been recovered from sites spanning three continents, from the sand quarries of Germany to the Middle Awash Valley of Ethiopia to the cave systems of southern Spain. Together, they document a large-brained, robust hominin that may have been the first to regularly hunt large game, construct shelters, and care for disabled group members.3

Yet for all its importance, H. heidelbergensis remains one of the most contentious taxa in paleoanthropology. The species was named in 1908 on the basis of a single mandible from Mauer, Germany, and the fossils subsequently assigned to it vary so widely in morphology, geography, and age that some researchers have called it a "wastebasket taxon" that obscures rather than clarifies evolutionary relationships.4, 5 Recent ancient DNA recovered from the Sima de los Huesos site has sharpened this debate, revealing that at least some populations traditionally classified as H. heidelbergensis were in fact early Neanderthals.6

Discovery and naming

The story of Homo heidelbergensis begins on 21 October 1907, when a worker named Daniel Hartmann pulled a massive, chinless mandible from a depth of 24 meters in the Grafenrain sand quarry near the village of Mauer, about 10 kilometers southeast of Heidelberg, Germany.7 The jaw was embedded in fluvial sediments of the Neckar river system, surrounded by the bones of Pleistocene megafauna including straight-tusked elephants, rhinoceroses, and horses. Otto Schoetensack, a lecturer at the University of Heidelberg who had been monitoring the quarry for years in hopes of just such a discovery, published a formal description the following year, erecting the new species Homo heidelbergensis.8

The Mauer mandible is strikingly robust, with a broad ascending ramus and a thick corpus, yet its teeth are surprisingly modern in size, falling within the range of living humans.7 It completely lacks a mentum osseum, the bony chin projection that is diagnostic of Homo sapiens. For over a century the specimen's age was estimated imprecisely, but in 2010 two independent radiometric techniques, combined electron spin resonance and uranium-series dating of associated mammalian teeth, and infrared radiofluorescence dating of sand grains, converged on an age of 609,000 ± 40,000 years.9

For decades after its discovery, the Mauer jaw remained an isolated curiosity. It was not until the mid-twentieth century that a series of African and European finds, including the Kabwe cranium from Zambia (1921), the Petralona skull from Greece (1960), and the Bodo cranium from Ethiopia (1976), provided enough material to flesh out the anatomy of a species that now appeared to span both continents.1, 10

Anatomy and morphology

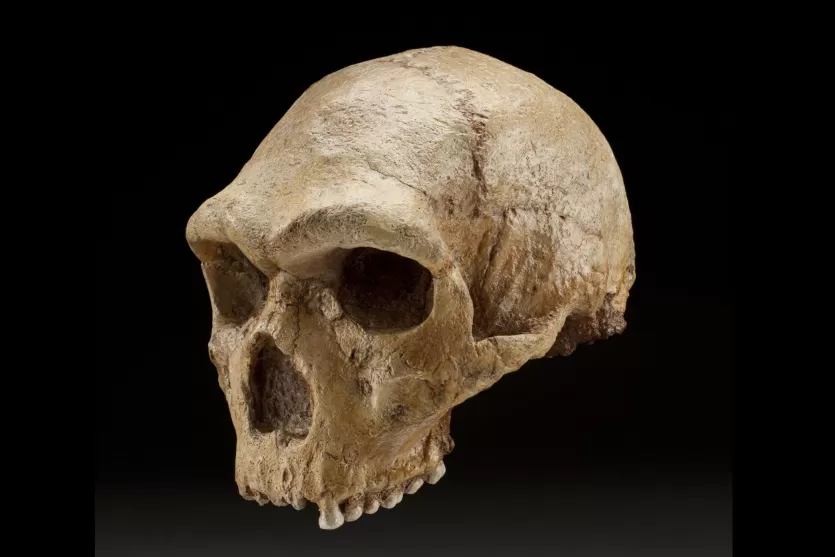

Homo heidelbergensis was a large-bodied, large-brained hominin. Cranial capacities range from approximately 1,100 to 1,400 cubic centimeters across the known sample, overlapping substantially with the lower end of the modern human range and significantly exceeding those of earlier Homo erectus populations, which typically fell between 600 and 1,100 cc.1, 3 The face was broad and projecting, with a prominent supraorbital torus (brow ridge) that forms a continuous bar across the frontal bone. The nasal aperture was wide, and the midface showed a degree of forward projection, or prognathism, intermediate between H. erectus and later Neanderthals.2

Postcranially, H. heidelbergensis was tall and powerfully built. Limb bones from the Sima de los Huesos site indicate that males stood approximately 175 centimeters tall and weighed around 62 kilograms, with females somewhat smaller.11 Body proportions were wide-bodied and cold-adapted in European populations, consistent with Bergmann's rule, the ecological generalization that organisms in colder climates tend to have larger, more compact bodies to conserve heat.12

The braincase of H. heidelbergensis sits morphologically between H. erectus and later hominins. The vault is lower and more elongated than in modern humans but higher and more rounded than in H. erectus. The occipital bone often bears a transverse torus, a horizontal ridge of thickened bone at the rear of the skull, though it is less pronounced than in H. erectus.13 In European specimens such as Petralona and the Sima de los Huesos crania, incipient Neanderthal features appear: the beginnings of a suprainiac fossa (a depression above the nuchal region), medial projection of the midface, and expansion of the occipital region, suggesting that the Neanderthal bauplan was emerging gradually within these populations.14, 11

Cranial capacity of key H. heidelbergensis specimens (cc)1, 10, 15

Key specimens

Bodo cranium (600 ka)

The Bodo cranium was discovered in 1976 by Alemayehu Asfaw in the Middle Awash Valley of the Afar region, Ethiopia, at a site called Bodo d'Ar.10 The specimen consists of a largely complete face and much of the frontal bone, with an estimated cranial capacity of approximately 1,250 cc. It is dated to around 600,000 years ago based on the associated fauna and argon-argon dating of overlying volcanic tuffs.10

What makes Bodo truly extraordinary are the cut marks that cover portions of its face. In 1986, Tim White published a detailed analysis demonstrating that these marks were made by stone tools applied to fresh bone, ruling out carnivore damage, root etching, or excavation trauma.16 The marks are concentrated around the orbits and across the frontal bone, in patterns consistent with the systematic removal of soft tissue. This constitutes the earliest solid evidence for deliberate defleshing of a hominin cranium, predating comparable evidence from Neanderthal sites by hundreds of thousands of years.16 Whether the defleshing reflects cannibalism, mortuary ritual, or trophy-taking remains unknown, as it is impossible to falsify any of these hypotheses with the available evidence. What is clear is that by 600,000 years ago, Middle Pleistocene hominins were engaging in complex behaviors directed at the bodies of the dead.16

Mauer 1 mandible (609 ka)

The holotype of H. heidelbergensis, Mauer 1 is a nearly complete mandible discovered in 1907 near Heidelberg, Germany, and formally described by Otto Schoetensack in 1908.8 Radiometric dating has established an age of 609 ± 40 ka.9 The jaw is remarkably robust, with a wide ascending ramus and a thick body, but it lacks any trace of a chin. Its dentition, however, is comparatively small and falls within the modern human range, creating a striking contrast between the primitive overall morphology and the relatively derived teeth.7, 9 Some researchers have argued that the Mauer mandible, as a European specimen showing no clear Neanderthal-derived features, may not be the ideal representative for a species that many now define primarily on the basis of African fossils.5

Kabwe 1 "Broken Hill" cranium (299 ka)

Discovered in 1921 during zinc mining at Broken Hill (now Kabwe) in what was then Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia), this nearly complete cranium was the first early human fossil found in Africa.17 Originally designated as the type specimen of Homo rhodesiensis by Arthur Smith Woodward, it has since been variously classified as H. heidelbergensis, H. rhodesiensis, or archaic H. sapiens.1 The cranium has an estimated capacity of approximately 1,280 cc, a massive supraorbital torus, and a broad, projecting face.17

For nearly a century, the age of Kabwe 1 was poorly constrained because the specimen was extracted unsystematically during mining operations, destroying its stratigraphic context. Estimates ranged from 125,000 to over 500,000 years. In 2020, Rainer Grün and colleagues applied direct uranium-series and electron spin resonance dating to the specimen itself, obtaining a best age estimate of 299 ± 25 ka.17 This surprisingly young age means that Kabwe 1 was contemporary with early Homo sapiens in Africa (the oldest known H. sapiens fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco, date to approximately 315 ka), implying that multiple hominin lineages coexisted on the continent during the late Middle Pleistocene.17, 18

Petralona cranium (~250 ka)

Found in 1960 by a villager in Petralona Cave in the Chalkidiki peninsula of northern Greece, this nearly complete cranium was encased in a thick layer of stalagmitic calcite.15 Its cranial capacity is approximately 1,220 cc. The specimen has been notoriously difficult to date: estimates range from 160,000 to over 700,000 years, though electron spin resonance dating of the surrounding calcite and contextual faunal associations suggest an age of roughly 200,000 to 400,000 years.15, 19

Morphologically, Petralona presents a mosaic of features. Its massive brow ridges, thick cranial walls, and occipital torus recall Homo erectus, while other aspects of its facial architecture and the shape of its braincase anticipate Neanderthal morphology.15 Chris Stringer's 1979 analysis placed the specimen closest to the African H. heidelbergensis specimens such as Kabwe, supporting the view that Middle Pleistocene populations in Europe and Africa were part of a broadly interconnected species.15 More recent assessments have noted that Petralona's combination of features may alternatively mark it as an early member of the Neanderthal lineage.14

Sima de los Huesos (~430 ka)

The Sima de los Huesos, or "Pit of Bones," is a small chamber at the bottom of a 13-meter vertical shaft deep within the Cueva Mayor cave system in the Sierra de Atapuerca, northern Spain. Since excavations began in 1984, the site has yielded more than 7,000 human fossils representing at least 28 individuals of all ages and both sexes, making it by far the largest assemblage of Middle Pleistocene hominins anywhere in the world.11 Uranium-series dating of a stalagmitic flowstone directly overlying the fossil-bearing sediments has established a minimum age of approximately 430,000 years.11

The Sima hominins were initially classified as H. heidelbergensis, but detailed morphological analysis has revealed that they already possess a suite of derived Neanderthal features, including midfacial prognathism, a suprainiac fossa, and specific dental traits, while retaining many primitive characteristics in the braincase and postcranial skeleton.11 Juan Luis Arsuaga and colleagues described them as representing an "early accumulation of Neanderthal-derived features," suggesting that the Neanderthal lineage was already differentiating by 430,000 years ago.11

The site's significance was further amplified by the extraction of ancient DNA. In 2013, Matthias Meyer and colleagues at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology recovered mitochondrial DNA from a Sima femur, and the result was startling: the mitochondrial sequence was more closely related to Denisovans than to Neanderthals.20 This unexpected finding was resolved in 2016 when the same team recovered nuclear DNA from two specimens, which clearly placed the Sima population on the Neanderthal branch of the hominin family tree.6 The discordance between nuclear and mitochondrial phylogenies suggests that the Neanderthal mitochondrial genome was replaced at some later point, possibly through gene flow from an African population ancestral to modern humans.6

How 28 individuals ended up at the bottom of a 13-meter shaft remains debated. The Atapuerca team has long argued that the bodies were deliberately deposited, which would make Sima de los Huesos one of the earliest known examples of funerary behavior. The only non-hominin artifact recovered from the pit is a single handaxe made of red quartzite, nicknamed "Excalibur," which Arsuaga has interpreted as a symbolic offering.11 Skeptics have proposed alternative explanations, including accidental falls, carnivore accumulation, or water transport, though the absence of carnivore gnaw marks on the human bones and the sheer number of individuals make these scenarios difficult to sustain.21

Specimen summary

Key Homo heidelbergensis specimens1, 9, 11, 17

| Specimen | Age (ka) | Location | Cranial capacity | Key features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mauer 1 | 609 ± 40 | Germany | N/A (mandible) | Holotype; robust, chinless mandible with modern-sized teeth |

| Bodo | ~600 | Ethiopia | ~1,250 cc | Stone-tool cut marks indicating deliberate defleshing |

| Sima de los Huesos | ~430 | Spain | 1,100–1,390 cc | 28+ individuals; nuclear DNA links to Neanderthals |

| Kabwe 1 | 299 ± 25 | Zambia | ~1,280 cc | First early human fossil from Africa; massive brow ridge |

| Petralona | ~200–400 | Greece | ~1,220 cc | Mosaic of H. erectus and Neanderthal traits |

The taxonomic debate

Few hominin species names generate as much disagreement as Homo heidelbergensis. The core problem is that the taxon has been used in at least three distinct ways by different researchers. In the broadest sense (sensu lato), it encompasses virtually all Middle Pleistocene hominins from both Africa and Europe that are neither H. erectus nor clearly Neanderthal or modern human. In a narrower European sense (sensu stricto), it refers specifically to the European lineage ancestral to Neanderthals. And in an exclusively African sense, it designates the African populations ancestral to H. sapiens, sometimes under the alternative name H. rhodesiensis.4, 5

At a 2019 conference session dedicated to defining the species, participants could not reach consensus; different researchers assigned different fossils and different meanings to the name.5 Ranthi Athreya argued in 2021 that the conceptual confusion surrounding H. heidelbergensis reflects broader problems in how paleoanthropologists define species, advocating for an ethnobiological reframing that emphasizes population-level variation over rigid type-specimen-based taxonomy.4

The most radical proposal came in 2021 from Mirjana Roksandic and colleagues, who argued that H. heidelbergensis should be abandoned entirely and replaced with a new species, Homo bodoensis, named after the Bodo cranium from Ethiopia.5 Under their scheme, the African and eastern Mediterranean Middle Pleistocene fossils ancestral to H. sapiens would be assigned to H. bodoensis, while European fossils showing derived Neanderthal features, including the Mauer mandible itself, would be reclassified as early Homo neanderthalensis.5 This proposal has generated both support and sharp criticism. Supporters argue it resolves "the muddle in the middle" by cleanly separating the African sapiens-ancestor lineage from the European Neanderthal-ancestor lineage. Critics counter that the Bodo cranium is too fragmentary to serve as a holotype for a new species, and that the proposal may simply replace one set of taxonomic problems with another.22

The debate is not merely academic nomenclature. How researchers classify Middle Pleistocene fossils directly affects how they reconstruct the evolutionary relationships among Neanderthals, Denisovans, and modern humans. If H. heidelbergensis is a single widespread species spanning Africa and Europe, it implies extensive gene flow across the Old World during the Middle Pleistocene. If the African and European populations represent distinct lineages, as the H. bodoensis proposal argues, it suggests an earlier divergence and less intercontinental connectivity.5, 23

The last common ancestor question

Homo heidelbergensis has long been cast as the last common ancestor (LCA) of Neanderthals, Denisovans, and modern humans, a role supported by its chronological position, geographic range, and intermediate morphology.1, 2 Molecular clock estimates based on nuclear DNA from both Neanderthal and Denisovan genomes place the divergence of the Neanderthal-Denisovan clade from the modern human lineage at approximately 550,000 to 765,000 years ago, with the Neanderthal-Denisovan split occurring somewhat later, around 390,000 to 440,000 years ago.23 These dates are broadly consistent with an LCA in the H. heidelbergensis time range.

The Sima de los Huesos nuclear DNA has refined this picture. The 2016 analysis by Meyer and colleagues showed that the Sima population, dated to ~430 ka, had already diverged from the Denisovan lineage and was more closely related to later Neanderthals.6 This establishes a hard minimum date for the Neanderthal-Denisovan split: it must have occurred before 430,000 years ago. It also means that the LCA of all three lineages (Neanderthals, Denisovans, and modern humans) must be older still, pushing it back to at least 500,000 to 700,000 years ago.6, 23

Some researchers have proposed alternative candidates for the LCA. Homo antecessor, known from the Gran Dolina site at Atapuerca and dated to approximately 800,000 years ago, has been suggested on the basis of its surprisingly modern-looking face.24 Proteomic analysis of an H. antecessor tooth published in 2020 supported a close relationship to the LCA of Neanderthals, Denisovans, and modern humans, though it could not determine whether H. antecessor was the ancestor itself or merely a close relative.24 A 2025 study of two Middle Pleistocene crania from China suggested that the sapiens lineage may extend back over a million years, substantially older than most H. heidelbergensis fossils, potentially complicating the species' claim to LCA status.25

Behavior and cognition

Homo heidelbergensis is associated with significant advances in hominin behavior. Populations attributed to this species produced sophisticated stone tools of the Acheulean tradition, including large, symmetrically flaked handaxes that required considerable skill and planning to manufacture.3 At some sites, including Boxgrove in England (~500 ka), the archaeological record preserves evidence of systematic hunting of large game such as horses and rhinoceroses, with stone tools showing impact damage consistent with use as spear tips or butchery implements.26

Wooden spears recovered from the site of Schöningen in Germany, dated to approximately 300,000 years ago, are among the oldest known hunting weapons. These spears, up to 2.3 meters long and carefully shaped with the center of gravity shifted forward for throwing, demonstrate aerodynamic understanding and the ability to plan complex, multi-step manufacturing sequences.27 Whether the Schöningen hominins are best classified as H. heidelbergensis or early Neanderthals is debated, but the spears fall within the temporal and geographic range of the species as traditionally defined.27

The Bodo cut marks, discussed above, represent the earliest known evidence of deliberate manipulation of a hominin body, whether for mortuary, ritual, or other purposes.16 The possible deliberate deposition of bodies at Sima de los Huesos, if confirmed, would extend the evidence for complex mortuary behavior back to 430,000 years ago.11 Together, these lines of evidence suggest that H. heidelbergensis possessed cognitive capabilities well beyond those of earlier hominins, including the capacity for forward planning, cooperative hunting, and possibly symbolic thought.3

Evolutionary significance

Whatever name ultimately prevails, the fossils grouped under Homo heidelbergensis document one of the most consequential transitions in human evolution: the emergence of the lineages that would produce Neanderthals, Denisovans, and modern humans from a common Middle Pleistocene ancestor.1, 2 The morphological evidence shows a clear trend from the generalized H. heidelbergensis condition toward the derived anatomies of later species. In Europe, this trajectory leads through the Sima de los Huesos population toward classic Neanderthals, with the progressive accumulation of midfacial prognathism, occipital bunning, and other diagnostic features.11, 14 In Africa, a parallel trajectory leads from specimens like Bodo and Kabwe toward the globular crania, reduced brow ridges, and prominent chins of Homo sapiens.17, 18

The ancient DNA revolution has added a new dimension to this picture. The Sima de los Huesos genome provides direct molecular evidence for the early divergence of the Neanderthal lineage, while the discordance between mitochondrial and nuclear phylogenies points to complex patterns of gene flow between Middle Pleistocene populations.6, 20 Models of early human population structure increasingly suggest that the Middle Pleistocene was not a simple branching tree but a network of partially isolated, partially interconnected populations exchanging genes across Africa, Europe, and western Asia.23

The taxonomic debate over H. heidelbergensis versus H. bodoensis reflects growing recognition that the Middle Pleistocene hominin fossil record is too complex to be neatly divided into discrete species with clear boundaries. Whether one name or several ultimately prevails, the fossils themselves remain powerful evidence that the human lineage did not spring into existence fully formed but emerged gradually, through hundreds of thousands of years of evolution across an entire continent, leaving behind a rich record of intermediate forms that connect our species to its deep evolutionary past.1, 5